Is it more of a disadvantage to be born poor or Black? Is it worse to be brought up by rich parents in a poor neighborhood, or by poor parents in a rich neighborhood? The answers to these questions lie at the very core of what constitutes a fair society. So how do we know if it is better to have wealthy parents or to grow up in a wealthy neighborhood when “good” things often go together (i.e., kids with rich parents grow up in rich neighborhoods)? When poverty, being Black, and living in a neighborhood with poor schools all predict worse outcomes, how can we disentangle them? Statisticians call this problem multicollinearity, and a number of straightforward methods using some of the largest databases on social mobility ever assembled provide surprisingly clear answers to these questions—the biggest obstacle children face in America is having the bad luck of being born into a poor family.

The immense impact of parental income on the future earnings of children has been established by a tremendous body of research. Raj Chetty and colleagues, in one of the largest studies of social mobility ever conducted,1 linked census data to federal tax returns to show that your parent’s income when you were a child was by far the best predictor of your own income when you became an adult. The authors write, “On average, a 10 percentile increase in parent income is associated with a 3.4 percentile increase in a child’s income.” This is a huge effect; children will earn an average of 34 percent more if their parents are in the highest income decile as compared to the lowest. This effect is true across all races, and Black children born in the top income quintile are more than twice as likely to remain there than White children born in the bottom quintile are to rise to the top. In short, the chances of occupying the top rungs of the economic ladder for children of any race are lowest for those who grow up poor and highest for those who grow up rich. These earnings differences have a broad impact on wellbeing and are strongly correlated with both health and life expectancy.2 Wealthy men live 15 years longer than the poorest, and wealthy women are expected to live 10 years longer than poor women—five times the effect of cancer!

Why is having wealthy parents so important? David Grusky at Stanford, in a paper on the commodification of opportunity, writes:

Although parents cannot directly buy a middleclass outcome for their children, they can buy opportunity indirectly through advantaged access to the schools, neighborhoods, and information that create merit and raise the probability of a middle-class outcome.3

In other words, opportunity is for sale to those who can afford it. This simple point is so obvious that it is surprising that so many people seem to miss it. Indeed, it is increasingly common for respected news outlets to cite statistics about racial differences without bothering to control for class. This is like conducting a study showing that taller children score higher on math tests without controlling for age. Just as age is the best predictor of a child’s mathematical ability, a child’s parent’s income is the best predictor of their future adult income.

Although there is no substitute for being born rich, outcomes for children from families with the same income differ in predictable and sometimes surprising ways. After controlling for household income, the largest racial earnings gap is between Asians and Whites, with Whites who grew up poor earning approximately 11 percent less than their Asian peers at age 40, followed by a two percent reduction if you are poor and Hispanic and an additional 11 percent on top of that if you are born poor and Black. Some of these differences, however, result from how we measure income. Using “household income,” in particular, conceals crucial differences between homes with one or two parents and this alone explains much of the residual differences between racial groups. Indeed, the marriage rates between races uncannily recapitulate these exact same earnings gaps—Asian children have a 65 percent chance of growing up in households with two parents, followed by a 54 percent chance for Whites, 41 percent for Hispanics and 17 percent for Blacks4 and the Black-White income gap shrinks from 13 percent to 5 percent5 after we control for income differences between single and two-parent households.

Just as focusing on household income obscures differences in marriage rates between races, focusing on all children conceals important sex differences, and boys who grow up poor are far more likely to remain that way than their sisters.6 This is especially true for Black boys who earn 9.7 percent less than their White peers, while Black women actually earn about one percent more than White women born into families with the same income. Chetty writes:

Conditional on parent income, the black-white income gap is driven entirely by large differences in wages and employment rates between black and white men; there are no such differences between black and white women.7

So, what drives these differences? If it is racism, as many contend, it is a peculiar type. It seems to benefit Asians, hurts Black men, and has no detectable effect on Black women. A closer examination of the data reveals their source. Almost all of the remaining differences between Black men and men of other races lie in neighborhoods. These disadvantages could be caused either by what is called an “individual-level race effect” whereby Black children do worse no matter where they grow up, or by a “place-level race effect” whereby children of all races do worse in areas with large Black populations. Results show unequivocal support for a place-level effect. Chetty writes:

The main lesson of this analysis is that both blacks and whites living in areas with large African-American populations have lower rates of upward income mobility.8

Multiple studies have confirmed this basic finding, revealing that children who grow up in families with similar incomes and comparable neighborhoods have the same chances of success. In other words, poor White kids and poor Black kids who grow up in the same neighborhood in Los Angeles are equally likely to become poor adults. Disentangling the effects of income, race, family structure, and neighborhood on social mobility is a classic case of multicollinearity (i.e., correlated predictors), with race effectively masking the real causes of reduced social mobility—parent’s income. The residual effects are explained by family structure and neighborhood. Black men have the worst outcomes because they grow up in the poorest families and worst neighborhoods with the highest prevalence of single mothers. Asians, meanwhile, have the best outcomes because they have the richest parents, with the lowest rates of divorce, and grow up in the best neighborhoods.

The impact that family structure has on the likelihood of success first came to national attention in 1965, when the Moynihan Report9 concluded that the breakdown of the nuclear family was the primary cause of racial differences in achievement. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, an American sociologist serving as Assistant Secretary of Labor (who later served as Senator from New York) argued that high out-of-wedlock birth rates and the large number of Black children raised by single mothers created a matriarchal society that undermined the role of Black men. In 1965, he wrote:

In a word, a national effort towards the problems of Negro Americans must be directed towards the question of family structure. The object should be to strengthen the Negro family so as to enable it to raise and support its members as do other families.10

A closer look at these data, however, reveals that the disadvantage does not come from being raised by a single mom but rather results from growing up in neighborhoods without many active fathers. In other words, it is not really about whether your own parents are married. Children who grow up in two-parent households in these neighborhoods have similarly low rates of social mobility. Rather, it seems to depend on growing up in neighborhoods with a lot of single parents. Chetty in a nearly perfect replication of Moynihan’s findings writes:

black father presence at the neighborhood level strongly predicts black boys’ outcomes irrespective of whether their own father is present or not, suggesting that what matters is not parental marital status itself but rather community-level factors.11

Although viewing the diminished authority of men as a primary cause of social dysfunction might seem antiquated today, evidence supporting Moynihan’s thesis continues to mount. The controversial report, which was derided by many at the time as paternalistic and racist, has been vindicated12 in large part because the breakdown of the family13 is being seen among poor White families in rural communities today14 with similar results. Family structure, like race, often conceals underlying class differences too. Across all races, the chances of living with both parents fall from 85 percent if you are born in an upper-middle-class family to 30 percent if you are in the lower-middle class.15 The take-home message from these studies is that fathers are a social resource and that boys are particularly sensitive to their absence.16 Although growing up rich seems to immunize children against many of these effects, when poverty is combined with absent fathers, the negative impacts are compounded.17

Children who grow up in families with similar incomes and comparable neighborhoods have the same chances of success. In other words, poor White kids and poor Black kids who grow up in the same neighborhood in Los Angeles are equally likely to become poor adults.

The fact that these outcomes are driven by family structure and the characteristics of communities that impact all races similarly poses a serious challenge to the bias narrative18—the belief that anti-Black bias or structural racism underlies all racial differences19 in outcomes—and suggests that the underlying reasons behind the racial gaps lie further up the causal chain. Why then do we so frequently use race as a proxy for the underlying causes when we can simply use the causes themselves? Consider by analogy the fact that Whites commit suicide at three times the rate of Blacks and Hispanics.20 Does this mean that being White is a risk factor for suicide? Indeed, the link between the income of parents and their children may seem so obvious that it can hardly seem worth mentioning. What would it even mean to study social mobility without controlling for parental income? It is the elephant in the room that needs to be removed before we can move on to analyze more subtle advantages. It is obvious, yet elusive; hidden in plain sight.

If these results are so clear, why is there so much confusion around this issue? In a disconcertingly ignorant tweet, New York Times writer Nikole Hanna-Jones, citing the Chetty study, wrote:

Please don’t ever come in my timeline again bringing up Appalachia when I am discussing the particular perils and injustice that black children face. And please don’t ever come with that tired “It’s class, not race” mess again.21

Is this a deliberate attempt to serve a particular ideology or just statistical illiteracy?22 And why are those who define themselves as “progressive” often the quickest to disregard the effects of class? University of Pennsylvania political science professor Adolph Reed put what he called “the sensibilities of the ruling class” this way:

the model is that the society could be one in which one percent of the population controls 95 percent of the resources, and it would be just, so long as 12 percent of the one percent were black and 14 percent were Hispanic, or half women.23

Perhaps this view and the conviction shared by many elites that economic redistribution is a non-starter accounts for this laser focus on racism, while ignoring material conditions. Racial discrimination can be fixed by simply piling on more sensitivity training or enforcing racial quotas. Class inequities, meanwhile, require real sacrifices by the wealthy, such as more progressive tax codes, wider distribution of property taxes used to fund public schools, or the elimination of legacy admissions at elite private schools.24 The fact that corporations and an educated upper class of professionals,25 which Thomas Piketty has called “the Brahmin left,”26 have enthusiastically embraced this type of race-based identity politics is another tell. Now, America’s rising inequality,27 where the top 0.1 percent have the same wealth as the bottom 90 percent, can be fixed under the guidance of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) policies and enforced by Human Resources departments. These solutions pose no threat to corporations or the comfortable lives of the elites who run them. We are obsessed with race because being honest about class would be too painful.

There are, however, also a number of aspects of human psychology that make the powerful impact of the class into which we are born difficult to see. First, our preference for binary thinking,28 which is less cognitively demanding, makes it easier to conjure up easily divisible, discrete, and visible racial categories (e.g., Black, White, Asian), rather than the continuous and often less visible metric of income. We run into problems when we think about continuous variables such as income, which are hard to categorize and can change across our lifetimes. For example, what is the cutoff between rich and poor? Is $29,000 dollars a year poor but $30,000 middle class? This may also help to explain why we are so reluctant to discuss other highly heritable traits that impact our likelihood of success, like attractiveness and intelligence. Indeed, a classic longitudinal study by Blau and Duncan in 196729 which studied children across the course of their development suggests that IQ might be an even better predictor of adult income than their parent’s income. More recently Daniel Belsky found that an individual’s education-linked genetics consistently predicted a change in their social mobility, even after accounting for social origins.30 Any discussion of IQ or innate differences in cognitive abilities has now become much more controversial, however, and any research into possible cognitive differences between populations is practically taboo today. This broad denial of the role of genetic factors in social mobility is puzzling, as it perpetuates the myth that those who have succeeded have done so primarily due to their own hard work and effort, and not because they happened to be beneficiaries of both environmental and genetic luck. We have no more control over our genetic inheritance than we do over the income of our parents, their marital status, or the neighborhoods in which we spend our childhoods. Nevertheless, if cognitive differences or attractiveness were reducible to clear and discrete categories, (e.g., “dumb” vs. “smart” or “ugly” vs. “attractive”) we might be more likely to notice them and recognize their profound effects. Economic status is also harder to discern simply because it is not stamped on our skin while we tend to think of race as an immutable category that is fixed at birth. Race is therefore less likely to be seen as the fault of the hapless victim. Wealth, however, which is viewed as changeable, is more easily attributed to some fault of the individual, who therefore bears some of the responsibility for being (or even growing up) poor.

We may also fail to recognize the effects of social class because of the availability bias31 whereby our ability to recall information depends on our familiarity with it. Although racial segregation has been falling32 since the 1970s, economic segregation has been rising.33 Although Americans are interacting more with people from different races, they are increasingly living in socioeconomic bubbles. This can make things such as poverty and evictions less visible to middle-class professionals who don’t live in these neighborhoods and make problems with which they may have more experience, such as “problematic” speech, seem more pressing.

Still, even when these studies are published, and the results find their way into the media, they are often misinterpreted. This is because race can mask the root causes of more impactful disadvantages, such as poverty, and understanding their inter-relations requires a basic understanding of statistics, including the ability to grasp concepts such as multicollinearity.

Of course, none of this is to say that historical processes have not played a crucial role in producing the large racial gaps we see today. These causes, however, all too easily become a distraction that provides little useful information about how to solve these problems. Perhaps reparations for some people, or certain groups, are in order, but for most people, it simply doesn’t matter whether your grandparents were impoverished tenant farmers or aristocrats who squandered it all before you were born. Although we are each born with our own struggles and advantages, the conditions into which we are born, not those of our ancestors, are what matter, and any historical injustices that continue to harm those currently alive will almost always materialize in economic disparities. An obsession with historical oppression which fails to improve conditions on the ground is a luxury34 that we cannot afford. While talking about tax policy may be less emotionally satisfying than talking about the enduring legacy of slavery, redistributing wealth in some manner to the poor is critical to solving these problems. These are hard problems, and solutions will require acknowledging their complexity. We will need to move away from a culture that locks people into an unalterable hierarchy of suffering, pitting groups that we were born into against one another, but rather towards a healthier identity politics that emphasizes economic interests and our common humanity.

Most disturbing, perhaps, is the fact that the institutions that are most likely to promote the bias narrative and preach about structural racism are those best positioned to help poor children. Attending a four-year college is unrivaled in its ability to level the playing field for the most disadvantaged kids from any race and is the most effective path out of poverty,35 nearly eliminating any other disadvantage that children experience. Indeed, the poorest students who are lucky enough to attend elite four-year colleges end up earning only 5 percent less than their richest classmates.36 Unfortunately, while schools such as Harvard University tout their anti-racist admissions policies,37 admitting Black students in exact proportion to their representation in the U.S. population (14 percent), Ivy League universities are 75 times more likely38 to admit children born in the top 0.1 percent of the income distribution as they are to admit children born in the bottom 20 percent. If Harvard was as concerned with economic diversity as racial diversity, it would accept five times as many students from poor families as it currently does. Tragically, the path most certain to help poor kids climb out of poverty is closed to those who are most likely to benefit.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 28.3

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

Decades of social mobility research has come to the same conclusion. The income of your parents is by far the best predictor of your own income as an adult. By using some of the largest datasets ever assembled and isolating the effects of different environments on social mobility, research reveals again and again how race effectively masks parental income, neighborhood, and family structure. These studies describe the material conditions of tens of millions of Americans. We are all accidents of birth and imprisoned by circumstances over which we had no control. We are all born into an economic caste system in which privilege is imposed on us by the class into which we are helplessly born. The message from this research is that race is not a determinant of economic mobility on an individual level.39 Even though a number of factors other than parental income also affect social mobility, they operate on the level of the community.40 And although upward mobility is lower for individuals raised in areas with large Black populations, this affects everyone who grows up in those areas, including Whites and Asians. Growing up in an area with a high proportion of single parents also significantly reduces rates of upward mobility, but once again this effect operates on the level of the community and children with single parents do just as well as long as they live in communities with a high percentage of married couples.

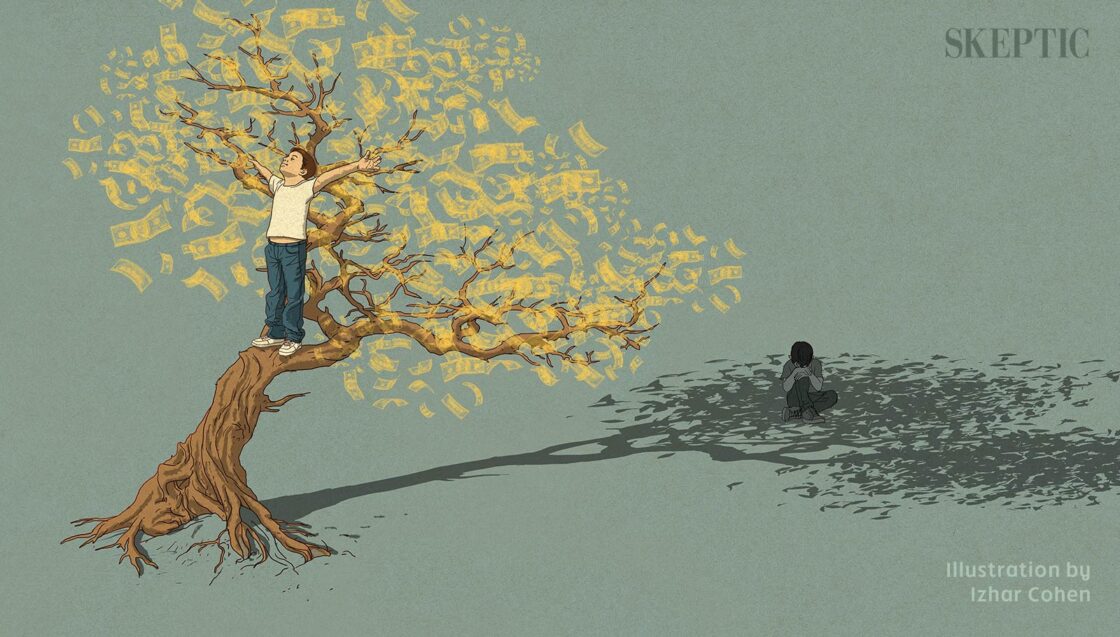

One thing these data do reveal—again, and again, and again—however, is that privilege is real. It’s just based on class, not race. ![]()

About the Author

Robert Lynch is an evolutionary anthropologist at Penn State who specializes in how biology, the environment, and culture transact to shape life outcomes. His scientific research includes the effect of religious beliefs on social mobility, sex differences in social relationships, the impact of immigration on social capital, how social isolation can promote populism, and the evolutionary function of laughter.

References

- https://rb.gy/n0b2s

- https://rb.gy/hyrbb

- https://rb.gy/e72y9

- https://rb.gy/borp3

- https://rb.gy/hhbv7

- https://rb.gy/4y12m

- https://rb.gy/ws3ri

- https://rb.gy/885jf

- https://rb.gy/swsnm

- https://rb.gy/fqske

- https://rb.gy/xamwr

- https://rb.gy/6hgl4

- https://rb.gy/gyd8f

- https://rb.gy/wevmn

- https://rb.gy/8603b

- https://rb.gy/j31um

- https://rb.gy/njjfe

- https://rb.gy/zey0m

- Ibid.

- https://rb.gy/tvgor

- https://rb.gy/m8d6d

- https://rb.gy/hjnr1

- https://rb.gy/vhiqi

- https://rb.gy/ci5jd

- https://rb.gy/1x19z

- https://rb.gy/il8nx

- https://rb.gy/5wkgb

- https://rb.gy/du3le

- https://rb.gy/ayncj

- https://rb.gy/6h3e4

- https://rb.gy/kav1r

- https://rb.gy/sp0vu

- https://rb.gy/d61g7

- https://rb.gy/6n3r3

- https://rb.gy/7wi4s

- https://rb.gy/dd5gp

- https://rb.gy/bwrqt

- https://rb.gy/5jsod

- https://rb.gy/wg63i

- https://rb.gy/dj43h

This article was published on December 27, 2023.