In recent discussions about the “replication crisis” in science, in addition to a large percentage of famous psychology experiments failing to replicate, suggestions have also been made that some classic psychology experiments could not be conducted today due to ethical or practical concerns, the most notable being that of Stanley Milgram’s famous shock experiments. In fact, in 2010, Dr. Michael Shermer, working with Chris Hansen and Dateline NBC producers, replicated a number of classic psychology experiments, including Milgram. What follows is a summary of that research, from Chapter 9, Moral Regress, in Dr. Shermer’s book The Moral Arc, along with the two-part episode from the Dateline NBC show, called “What Were You Thinking?”

In 2010, I worked on a Dateline NBC two-hour television special in which we replicated a number of now classic psychology experiments, including that of Yale University professor Stanley Milgram’s famous shock experiments from the early 1960s on the nature of evil. Here we provide links to the two-part segment television episodes of our replication of Milgram.

In public talks in which I screen these videos I am occasionally asked how we got this replication passed by an Institutional Review Board (an IRB), which is required for scientific research, inasmuch as such experiments could never be conducted today. We didn’t. This was for network television, not an academic laboratory, so the equivalent of an IRB was review by NBC’s legal department, which approved it. This seems to surprise — even shock — many academics, until I remind them of what people do to one another on reality television programs in which subjects are stranded on remote islands or thick jungles and left to fend for themselves — sometimes naked and afraid — in various contrivances that resemble a Hobbesian world of a war of all against all.

Watch Replicating Milgram on Dateline NBC’s special “What Were You Thinking?” Part 1 & 2 (playlist)

Shock and Awe in a Yale Lab

Shortly after the war crimes trial of Adolf Eichmann began in Jerusalem in July of 1961, psychologist Stanley Milgram devised a set of experiments, the aim of which was to better understand the psychology behind obedience to authority. Eichmann had been one of the chief orchestrators of the Final Solution but, like his fellow Nazis at the Nuremberg trials, his defense was that he was innocent by virtue of the fact that he was only following orders. Befehl ist Befehl — orders are orders — is now known as the Nuremberg defense, and it’s an excuse that seems particularly feeble in a case like Eichmann’s. “My boss told me to kill millions of people so — hey — what could I do?” is not a credible defense. But, Milgram wondered, was Eichmann unique in his willingness to comply with orders, no matter how atrocious? And just how far would ordinary people be willing to go?

A contestant for our faux television reality show “What a Pain!” talks to our actors playing the learner and the authority to be obeyed.

Obviously Milgram could not have his experimental subjects gas or shoot people, so he chose electric shock as a legal nonlethal substitute. Looking for subjects to participate in what was billed as a “study of memory,” Milgram advertised on the Yale campus and also in the surrounding New Haven community. He said he wanted “factory workers, city employees, laborers, barbers, businessmen, clerks, construction workers, sales people, telephone workers,” not just the usual guinea pigs of the psychology lab, i.e., undergraduates participating for extra credit or beer money. Milgram assigned his subjects to the role of “teacher” in what was purported to be research on the effects of punishment on learning. The protocol called for the subject to read a list of paired words to the “learner” (who was, in reality, a shill working for Milgram), then present the first word of each pair again, upon which the learner was to recall the second word. Each time that the learner was incorrect, the teacher was to deliver an electric shock from a box with toggle switches in 15-volt increments that ranged from 15 volts to 450 volts, and featured such labels as Slight Shock, Moderate Shock, Strong Shock, Very Strong Shock, Intense Shock, Extreme Intensity Shock, and DANGER: Severe Shock, XXXX.1 Despite the predictions of 40 psychiatrists that Milgram surveyed before the experiment, who predicted that only one percent of subjects would go all the way to the end, 65 percent of subject completed the experiment, flipping that final toggle switch to deliver a shocking 450 volts, a phenomenon the social psychologist Philip Zimbardo characterizes as “the pornography of power.”1

Who was most likely to go the distance in maximal shock delivery? Surprisingly — and counter-intuitively — gender, age, occupation, and personality characteristics mattered little. Similar levels of punishment were delivered by the young and the old, by males and females, and by blue-collar and white-collar workers alike. What mattered most was physical proximity and group pressure. The closer the learner was to the teacher, the lower on the ladder of shock they climbed. And when Milgram added more confederates to encourage the teacher to administer ever more powerful shocks, most complied; when the confederate themselves rebelled against the authority figure’s instructions, the teacher was equally disinclined to obey. Nevertheless, 100 percent of Milgram’s subjects delivered at least a “strong shock” of 135 volts.3

Shock and Awe in a New York Studio

In our 2010 replication in a New York City studio, we tested six subjects who believed they were auditioning for a new reality show called “What a Pain!” We followed Milgram’s protocols and had our subjects read a list of paired words to a “learner” (an actor named Tyler), then present the first word of each pair again. When Tyler gave a prearranged incorrect answer, our subjects were instructed by an authority figure (an actor named Jeremy) to deliver an electric shock from a box modeled after Milgram’s contraption that, like ours, was just a hollow box that delivered no shocks at all.

Milgram characterized his experiments as testing “obedience to authority,” and most interpretations over the decades have focused on subjects’ unquestioning adherence to an authority’s commands. What I saw, however, was great reluctance and disquietude in all of our subjects nearly every step of the way. Our first subject, Emily, quit the moment she was told the protocol. “This isn’t really my thing,” she said with nervous laughter. When our second subject, Julie, got to 75 volts (having flipped five switches) she heard Tyler groan. “I don’t think I want to keep doing this,” she said.

Jeremy pressed the case: “Please continue.”

“No, I’m sorry,” Julie protested. “I don’t think I want to.”

“It’s absolutely imperative that you continue,” Jeremy insisted.

“It’s imperative that I continue?” Julie replied in defiance. “I think that — I’m like, I’m okay with it. I think I’m good.”

“You really have no other choice,” Jeremy said in a firm voice. “I need you to continue until the end of the test.”

Julie stood her ground: “No. I’m sorry. I can just see where this is going, and I just — I don’t — I think I’m good. I think I’m good to go. I think I’m going to leave now.”

At that point the show’s host Chris Hansen entered the room to debrief her and introduce her to Tyler, and then Chris asked Julie what was going through her mind. “I didn’t want to hurt Tyler,” she said. “And then I just wanted to get out. And I’m mad that I let it even go five [toggle switches]. I’m sorry, Tyler.”

Our contestant/subject Julie refuses to continue shocking the learner once he begins to cry out in pain.

Our third subject, Lateefah, started off enthusiastically enough, but as she made her way up the row of toggle switches, her facial expressions and body language made it clear that she was uncomfortable; she squirmed, gritted her teeth, and shook her fists with each toggled shock. At 120 volts she turned to look at Jeremy, seemingly seeking an out. “Please continue,” he authoritatively instructed. At 165 volts, when Tyler screamed “Ah! Ah! Get me out of here! I refuse to go on! Let me out!” Lateefah pleaded with Jeremy. “Oh my gosh. I’m getting all…like…I can’t…”; nevertheless Jeremy pushed her politely, but firmly, to continue. At 180 volts, with Tyler screaming in agony, Lateefah couldn’t take it anymore. She turned to Jeremy: “I know I’m not the one feeling the pain, but I hear him screaming and asking to get out, and it’s almost like my instinct and gut is like, ‘Stop,’ because you’re hurting somebody and you don’t even know why you’re hurting them outside of the fact that it’s for a TV show.” Jeremy icily commanded her to “please continue.” As Lateefah reluctantly turned to the shock box, she silently mouthed, “Oh my God.” At this point, as in Milgram’s experiment, we instructed Tyler to go silent. No more screams. Nothing. As Lateefah moved into the 300-volt range it was obvious that she was greatly distressed, so Chris stepped in to stop the experiment, asking her if she was getting upset. “Yeah, my heart’s beating really fast.” Chris then asked, “What was it about Jeremy that convinced you that you should keep going here?” Lateefah gave us this glance into moral reasoning about the power of authority: “I didn’t know what was going to happen to me if I stopped. He just — he had no emotion. I was afraid of him.”

Our fourth subject, a man named Aranit, unflinchingly cruised through the first set of toggle switches, pausing at 180 volts to apologize to Tyler after his audible protests of pain: “I’m going to hurt you and I’m really sorry.” After a few more rungs up the shock ladder, accompanied by more agonizing pleas by Tyler to stop the proceedings, Aranit encouraged him, saying, “Come on. You can do this. We are almost through.” Later, the punishments were peppered with positive affirmations. “Good.” “Okay.” After completing the experiment Chris asked, “Did it bother you to shock him?” Aranit admitted, “Oh, yeah, it did. Actually, it did. And especially when he wasn’t answering anymore.”

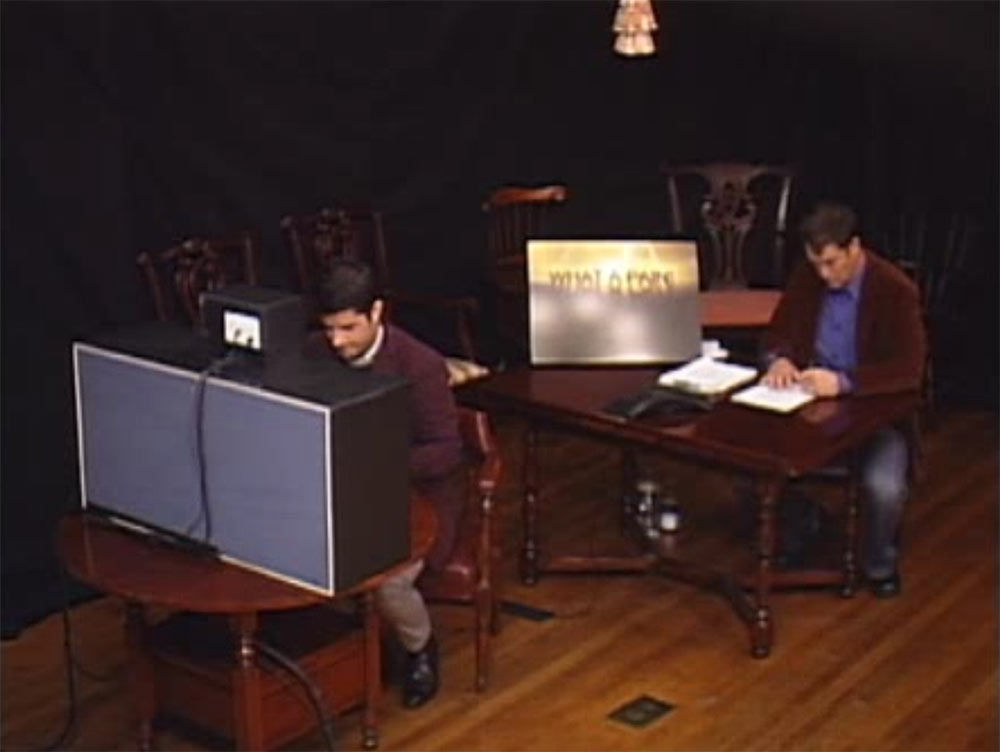

Our subject Aranit (left) continues shocking the learner upon the encouragement of our “authority” figure Jeremy (right).

Two other subjects in our replication, a man and a woman, went all the way to 450 volts, giving us a final tally of five out of six who administered shocks, and three who went all the way to the end of maximal electrical evil. All of the subjects were debriefed and assured that no shocks had actually been delivered, and after lots of laughs and hugs and apologies, everyone departed none the worse for wear.

Active Agents or Mindless Zombies?

What are we to make of these results? In the 1960s — the heyday of the Nurture Assumption4 — it was taken to mean that human behavior is almost infinitely malleable, and Milgram’s data seemed to confirm the idea that degenerate acts are primarily the result of degenerate environments (Nazi Germany being, perhaps, the ultimate example). In other words, evil is a matter of bad barrels, not bad apples.

Milgram’s interpretation of his data included what he called the “agentic state,” which is “the condition a person is in when he sees himself as an agent for carrying out another person’s wishes and they therefore no longer see themselves as responsible for their actions. Once this critical shift of viewpoint has occurred in the person, all of the essential features of obedience follow.” Subjects who are told that they are playing a role in an experiment are stuck in a no-man’s land somewhere between authority figure, in the form of a white lab-coated scientist, and stooge, in the form of a defenseless learner in another room. They undergo a mental shift from being moral agents in themselves who make their own decisions (that autonomous state) to the ambiguous and susceptible state of being an intermediary in a hierarchy and therefore prone to unqualified obedience (the agentic state).

Milgram believed that almost anyone put into this agentic state could be pulled into evil one step at a time — in this case 15 volts at a time — until they were so far down the path there was no turning back. “What is surprising is how far ordinary individuals will go in complying with the experimenter’s instructions,” Milgram recalled. “It is psychologically easy to ignore responsibility when one is only an intermediate link in a chain of evil action but is far from the final consequences of the action.” This combination of a step-wise path, plus a self-assured authority figure that keeps the pressure on at every step, is the double whammy that makes evil of this nature so insidious. Milgram broke the process down into two stages: “First, there is a set of ‘binding factors’ that lock the subject into the situation. They include such factors as politeness on his part, his desire to uphold his initial promise of aid to the experimenter, and the awkwardness of withdrawal. Second, a number of adjustments in the subject’s thinking occur that undermine his resolve to break with the authority. The adjustments help the subject maintain his relationship with the experimenter, while at the same time reducing the strain brought about by the experimental conflict.”5

Put yourself into the mind of one of these subjects — either in Milgram’s experiment or in our NBC replication. It’s an experiment conducted at the prestigious Yale University — or at a studio set up by a major television network. It’s being supervised by an established institution — a national university or a national network. It’s for science — or it’s for television. It’s being run by a white-lab-coated scientist — or by a television director. The authorities overseeing the experiment are either university professors or network executives. An agent — someone carrying out someone else’s wishes under such conditions — would feel in no position to object. And why should she? It’s for a good cause, after all — the advancement of science, or the development of a new and interesting television series.

Dr. Shermer explains for the television audience why people commit evil acts.

Out of context, if you ask people — even experts, as Milgram did — how many people would go all the way to 450 volts, they lowball the estimate by a considerable degree, as Milgram’s psychiatrists did. As Milgram later reflected: “I am forever astonished that when lecturing on the obedience experiments in colleges across the country, I faced young men who were aghast at the behavior of experimental subjects and proclaimed they would never behave in such a way, but who, in a matter of months, were brought into the military and performed without compunction actions that made shocking the victim seem pallid.”6

In the sociobiological and evolutionary psychology revolutions of the 1980s and 1990s, the interpretation of Milgram’s results shifted toward the nature/biological end of the spectrum from its previous emphasis on nurture/environment. The interpretation softened somewhat as the multidimensional nature of human behavior was taken into account. As it is with most human action, moral behavior is inextricably complex and includes an array of causal factors, obedience to authority being just one among many. The shock experiments didn’t actually reveal just how primed all of us are to inflict violence for the flimsiest of excuses; that is, it isn’t a simple case of bad apples looking for a bad barrel in order to cut loose. Rather the experiments demonstrate that all of us have conflicting moral tendencies that lie deep within.

Our moral nature includes a propensity to be sympathetic, kind, and good to our fellow kith and kin, as well as an inclination to be xenophobic, cruel, and evil to tribal Others. And the dials for all of these can be adjusted up and down depending on a wide range of conditions and circumstances, perceptions and states of mind, all interacting in a complex suite of variables that are difficult to tease apart. In point of fact, most of the 65 percent of Milgram’s subjects who went all the way to 450 volts did so with great anxiety, as did the subjects in our NBC replication. And it’s good to remember that 35 percent of Milgram’s subjects were exemplars of the disobedience to authority — they quit in defiance of what the authority figure told them to do. In fact, in a 2008 partial replication by the social psychologist Jerry Burger, in which he ran the voltage box only up to 150 volts (the point at which the “learner” in Milgram’s original experiment began to cry out in pain), twice as many subjects refused to obey the authority figure. Assuming these subjects were not already familiar with the experimental protocols, the findings are an additional indicator of moral progress from the 1960s to the 2000s caused, I would argued, by that ever-expanding moral sphere and our collective capacity to take the perspective of another, in this case the to-be-shocked learner.7

Alpinists of Evil

Milgram’s model comes dangerously close to suggesting that subjects are really just puppets devoid of free will, which effectively lets Nazi bureaucrats off the hook as mere agentic automatons in an extermination engine run by the great paper-pushing administrator, Adolf Eichmann (whose actions as an unremarkable man in a morally bankrupt and conformist environment were famously described by Hannah Arendt as “the banality of evil.”). The obvious problem with this model is that there can be no moral accountability if an individual is truly nothing more than a mindless zombie whose every action is controlled by some nefarious mastermind. Reading the transcript of Eichmann’s trial is mind numbing (it goes on for thousands of pages), as he both obfuscates his real role while shifting the blame entirely to his overseers, as in this statement:

What I said to myself was this: The Head of State has ordered it, and those exercising judicial authority over me are now transmitting it. I escaped into other areas and looked for a cover for myself which gave me some peace of mind at least, and so in this way I was able to shift — no, that is not the right term — to attach this whole thing one hundred percent to those in judicial authority who happened to be my superiors, to the head of State — since they gave the orders. So, deep down, I did not consider myself responsible and I felt free of guilt. I was greatly relieved that I had nothing to do with the actual physical extermination.8

The last statement might possibly be true — given how many battle-hardened SS soldiers were initially sickened at the site of a killing action — but the rest is pure spin-doctored malarkey and Arendt allowed herself to be taken in by it more than reason would allow, as the historian David Cesarani shows in his revealing biography Becoming Eichmann and as recounted in Margarethe von Trotta’s moving film Hanna Arendt.9 The evidence of Eichmann’s real role in the Holocaust was plain for all to see at the time, as dramatically re-enacted in Robert Young’s 2010 biopic entitled simply Eichmann, based on the transcripts of the interrogation of and confession by Eichmann just before his trial, conducted by the young Israeli police officer Avner Less, whose father was murdered in Auschwitz.10 Time and again, throughout hundreds of recorded hours, Less queries Eichmann about transports of Jews and gypsies sent to their death, all followed by denials and lapses of memory. Less then presses the point by showing Eichmann copies of transport documents with his signature at the bottom, leading Eichmann to say in an exasperated voice, “what’s your point?”

The point is that there is a mountain of evidence proving that Eichmann — like all the rest of the Nazi leadership — were not simply following orders. As Eichmann himself boasted when he wasn’t on trial: “When I reached the conclusion that it was necessary to do to the Jews what we did, I worked with the fanaticism a man can expect from himself. No doubt they considered me the right man in the right place…. I always acted 100 per cent, and in giving of order I certainly was not lukewarm.” As the Holocaust historian Daniel Jonah Goldhagen asks rhetorically, “Are these the words of a bureaucrat mindlessly, unreflectively doing his job about which he has no particular view?”11

The historian Yaacov Lozowick characterized the motives in his book Hitler’s Bureaucrats, in which he invokes a mountain-climbing metaphor: “Just as a man does not reach the peak of Mount Everest by accident, so Eichmann and his ilk did not come to murder Jews by accident or in a fit of absent-mindedness, nor by blindly obeying orders or by being small cogs in a big machine. They worked hard, thought hard, took the lead over many years. They were the alpinists of evil.”12

About the Author

Dr. Michael Shermer is the Founding Publisher of Skeptic magazine, the host of the Science Salon Podcast, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University where he teaches Skepticism 101. For 18 years he was a monthly columnist for Scientific American. He is the author of New York Times bestsellers Why People Believe Weird Things and The Believing Brain, Why Darwin Matters, The Science of Good and Evil, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His new book is Giving the Devil His Due: Reflections of a Scientific Humanist.

References

- Milgram, Stanley. 1969. Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View. New York: Harper.

- Interview with Phil Zimbardo conducted by the author on March 26, 2007.

- Milgram, 1969.

- Harris, Judith Rich. 1998. The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do. New York: Free Press.

- Milgram, 1969.

- Ibid.

- Burger, Jerry. 2009. “Replicating Milgram: Would People Still Obey Today?” American Psychologist, 64, 1–11.

- The Trial of Adolf Eichmann, Session 95, July 13, 1961. https://bit.ly/35AzK8W

- Cesarani, David. 2006. Becoming Eichmann: Rethinking the Life, Crimes, and Trial of a “Desk Murderer”. New York: De Capo Press. Von Trotta, Margarethe (Director). 2012. Hannah Arendt. Zeitgeist Films. See also: Lipstadt, Deborah E. 2011. The Eichmann Trial. New York: Schocken.

- Young, Robert. 2010. Eichmann. Regent Releasing, Here! Films. October.

- Quoted in: Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah. 2009. Worse Than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity. New York: PublicAffairs, 158.

- Lozowick, Yaacov. 2003. Hitler’s Bureaucrats: The Nazi Security Police and the Banality of Evil. New York: Continuum, 279.

This article was published on October 2, 2020.

People certainly don’t behave like automatons – they can act very differently under circumstances which may seem to be only slightly differently. One motive which is very powerful for humans – as for other social animals – is the need to do what the group does or expects. The group presumably was originally identified as a family group or small tribe but in modern society can be a nation, a religion, a political party or any number of other non-genetic groups. If an individual authority is perceived as representing a group, his commands must be more imperative. Obviously the commands of a national leader such as Hitler carry much more weight than those of scientist in a lab, regardless of any agreements that are made beforehand. There is no doubt whatsoever that people will act very cruelly, contrary to their own supposed morality, when acting for their group – wars as well as torture camps would not be possible if they didn’t. To really replicate the situation in war or torture camps (for example) the interests of the group with which the subject identifies would have to be invoked.

Can i speak is such a fashion as follows and retain the sacred space needed for such dialogue? Michael is true to his libertarian roots in the first paragraph…essentially saying because ‘they’ do this and worse, and it wasn’t against the law, the academics are appeased, or quieted or at worse dismissed relative to any concerns raised. The law is the basic ground upon which rests ethics; which gestures toward a morality of sorts, ultimately longing for the most aspirational expression/enactment of virtue. (So reckless here to try to create sacred space with such few words!….)i love these sorts of replication studies and enjoy the outcome as a professional psychologist yet wouldn’t it have been more admirable to not simply seek to justify his actions, Michael could have said perhaps this was not his best moment and remind us that we never should judge a person by their less than best or worse moments. There is no way a man as thoughtful as Michael Shermer would ever suggest that just because something is it is legal, do it!

It would be interesting to consider the test subjects religion. Does holding strong beliefs in God and the teachings stemming from such a background and upbringing have an effect?

It would definitely be interesting. I think if subjects held strong beliefs in God and the teachings stemming from such a background, they would be more likely to obey, and to administer the strongest of shocks.

Some may but then again some may not. A strong belief in God could override the act of obedience.

I first became aware of the Milgram experiments when I saw part of a TV Film called, “The Tenth Level” back in the 1970s. It starred William Shatner and I was a huge Star Trek van, so I watched more of the movie than you’d think a kid would stick around for. I’ll have to surf around and see if the film is available online now that I am old enough to understand it better.