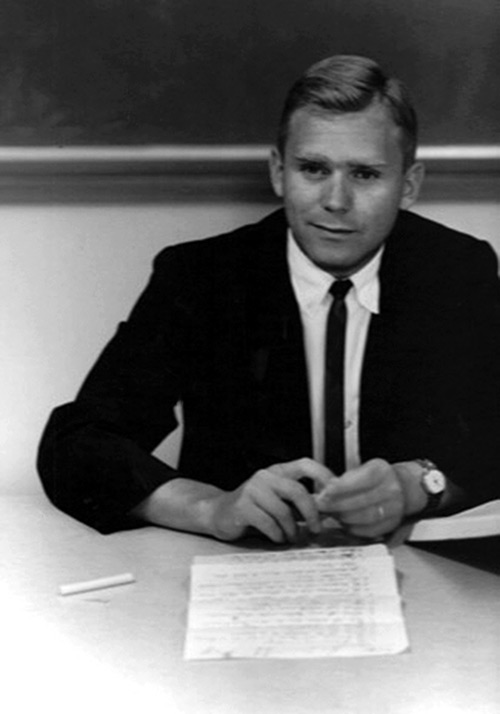

Since skeptics talk a lot about critical thinking it is important to note that the world of critical thinking lost a significant champion on August 30th 2015. After a lengthy battle with Parkinson’s disease Dr. Richard Paul passed away. Richard was the founder and iconic force behind the Foundation for Critical Thinking, headquartered in Sonoma County, California.

This is going to sound like a strange way to begin a tribute, but in the 15 years that I knew him, Richard never taught me a thing. And yet I learned so much. In fact, it would be difficult to adequately describe the profound effect he and his work have had on my life. This notion about the differences between teaching and learning is one of the things that I took from my work with Richard and the Foundation. It is not a minor contrast in mindset or approach—it affects everything. Learning is active, participative and rewards questioning. Perhaps most importantly, learning is how humans construct knowledge of the world. He saw the teacher as a coach to support learning and not an oracle of information to be pleased with predetermined correct answers. As he used to say, “If the coach is sweating, there is a problem.” It is the learner who should be doing the work. Many classrooms are unfortunately full of sweating teachers. So are conferences and other “learning” events.

Dr. Paul saw critical thinking as a way of understanding thinking in general, applying standards to thinking, and where needed improving thinking. No one sets out to think poorly, of course, and yet we do. Critical thinking is an antidote to this problem. His conception of critical thinking was the most complete that I have encountered. Richard did not conceive of critical thinking as simply a tool for solving particular problems, but as a way of understanding and working on all of life with a purpose. That purpose was to make life better for the living. He felt that in order to achieve this purpose, critical thinking could not be divorced from ethics. In other words, it couldn’t just a be a set of tools that you practiced so that you could manipulate particular outcomes, but a way of thinking and living that leads to better lives for all of us. He called this “strong sense critical thinking”—it is strategic thinking in service of a life and not just in service of some tactical consideration.

Dr. Paul’s most enduring and important contribution will be the development of a model that allows for the systematic development of critical thinking skills. This is a keystone requirement for improving thinking on a population-wide basis. I have known many decent thinkers and some great ones, but two things were always troubling. What standards do we use to determine how good the thinking really is and, even if it turns out to be great, how do we teach others to adopt these habits? The model that he built contains three interlocking components:

- The Elements of Thought—the parts of thinking that are present in all thinking.

- The Intellectual Standards—the measurement criteria for the quality of thinking.

- The Intellectual Traits—capacities that a thinker has and should develop.

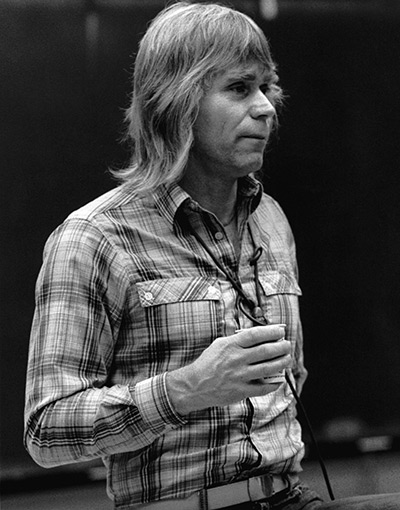

Richard along with his wife of 20 years and chief collaborator, Dr. Linda Elder, authored many publications providing detailed support for the model, including a series of mini-guides that highlight particular issues in the model, along with barriers to the adoption of critical thinking. He didn’t invent the components of the model, but as Steve Jobs once said, “Creativity is just connecting things.” Jobs had a gift for seeing what was fundamental, for seeing the things that transcended the specifics or novelty of situations.

Through their foundation, Richard and Linda offered an annual international conference in and around Sonoma and the Bay Area (that conference will continue). I was fortunate to give presentations at several of them. The conferences are very participative and require the practice of the model from the beginning of the event to the end. There are few conventional lectures, but I saw Dr. Paul give several excellent keynotes over the years. My favorite perhaps was the “Top Ten Ways to Impair Student Learning”—sadly, all ten were (and are!) in constant circulation in the public and private schools of North America and serve as a painful contrast to a critical thinking approach.

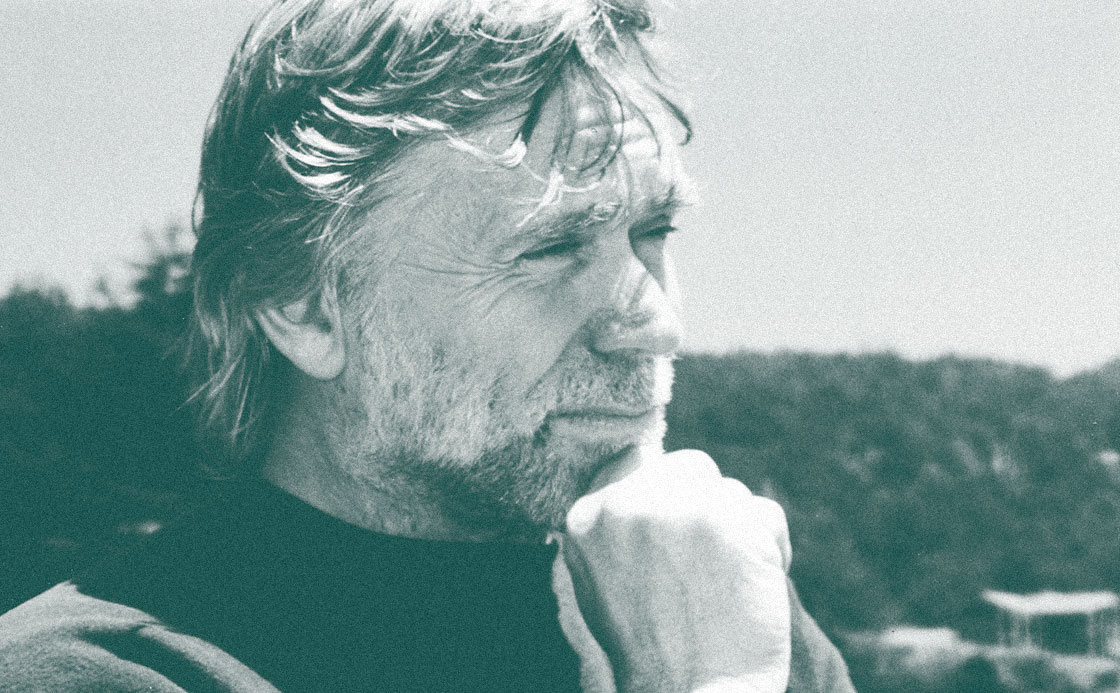

Richard was one of those people who loved what he did, so in that sense he never worked a day in his life. He also lived the ideals, practiced the model with discipline and conviction, while creating the space for others to do so as well. He modeled his program with patient listening, relevant and important questions, and a subtle but incisive and twinkling sense of humor. He wanted to help build more critical societies. According to the foundation’s obituary:

Paul established the first Center for Critical Thinking worldwide in 1980 at Sonoma State University in Northern CA and established the Foundation for Critical Thinking in 1991, to support the work of the Center. The work of the Foundation for Critical Thinking is widely used in education, at all levels of instruction, where critical thinking is to be found. It is also advanced in the current Army Field Manual for all military leadership education in critical thinking. Due largely to Paul’s work and the theoretical foundations of critical thinking he developed over a lifetime, Paul revolutionized the way in which critical thinking is conceptualized in academia and in intellectual communities across the world. Paul wrote eight books and more than 200 articles on critical thinking, including his early seminal work on critical thinking published in 1992 entitled: Critical Thinking: What Every Person Needs to Survive in a Rapidly Changing World. Throughout his life, Paul wrote books for every grade level and developed extensive teaching tactics and strategies that advance critical thinking in instruction.

I will miss him. I wish I had been able to spend more time with him. We are fortunate that he has left such a generous legacy and that Linda and the rest of the Foundation will continue the work. We all have a lot at stake in building societies that think more critically and the tools that are available through his work make that possible. I encourage readers to visit the links to his obituary to see more details of his fascinating life and to look into the model he developed through the Foundation for Critical Thinking. And in his memory, may we all continue working towards building more critical societies. Here is a good place to start. ![]()

About the Author

Greg Hart spends his time designing the invisible but powerful influences on behavior. He has a formal background in ergonomics and kinesiology. He can tell you exactly why sitting is one of the most dangerous things you could ever do. His work and research in ergonomics is fed by a fascination with the relationship between explicit and subconscious behaviour and how the effects are felt in the world — from offices to helicopters to muddy trenches and into Urban Ergonomics (how citizens interact with the built and natural environment of their cities and towns). He has published and presented on the impact of human nature on design, strategy and process. Greg is a lifelong student and advocate of critical thinking — he leads workshops and helps organizations embed the principles in the work they do. He lives in Calgary, Alberta.

This article was published on October 14, 2015.

What are the “Top Ten Ways to Impair Student Learning”? I can’t find any reference to it on the web, not even at the Centre for Critical Thinking.