The Abortion Debate in Context

In the mid-1980s, demographer Ron Lesthaeghe staked his career on an undiscovered—and shocking—aspect of human societies he had been documenting.1 Birth rates had rapidly slowed in the most industrialized countries and were steadily slowing across developing countries. Family structures were also changing rapidly, including more people getting divorced and living alone or raising children alone.

Demographers and social scientists today2 know this phenomenon as the “second demographic transition.” But you certainly don’t need to be a demographer to see that family life is changing.

As women, the working class, and others have increasingly accessed occupational, educational, and political opportunities previously denied to them, more and more people are getting married later in life and having fewer children. Why? Because they are prioritizing career specialization over longer periods so as to be competitive in the growing global marketplace. More people in the world today are reaping the rewards of economic specialization than at any time in human history.

It is a fascinating transitional period. And it is, in significant part, a transitional period of family formation and of reproduction. Amongst other things, the ability for women to control their reproduction has been key to their success in higher education and high career achievement. The birth control pill was approved by the FDA in 1960, and this, along with many other factors, changed the demographics of colleges, universities, and the labor force forever.

It is in this complex and dynamic context that we find our culture embroiled in a national debate over abortion access.

The history of abortion legislation in the United States is a punitive and heavy-handed one. Every state in the U.S. had outlawed abortion by 1910, and, by 1967, 49 states classified commission of abortion as a felony crime.3

However, things had begun to change in the late 1960s. By the mid-1970s, a third of U.S. states had adopted legal allowances for abortion under circumstances of medical emergency. And, of course, in 1973 the landmark Roe v. Wade ruling came out. What made Roe (along with its peer Doe v. Bolton) powerful was its framing of abortion access as a right that state laws could not constitutionally restrict.

Over a dozen Supreme Court rulings have since followed, clarifying what is required from women, and what protections women have when getting an abortion. But the bombshell ruling repealing Roe v. Wade in June 2022 thrust the issue back into public discourse. Though economic recession, crime, and healthcare continued to be Americans’ top concerns heading into the 2022 midterm elections, Pew Research Center polling found abortion was a “very important” issue to 56 percent of registered voters, up from 43 percent four months earlier.4 Looking first towards within-party primary elections, many Republican politicians are in an arms race to top one another on how restricted they want to make abortion so as to appeal to their conservative base, even while realizing that this extreme position could backfire in general elections because most Americans support relatively liberal abortion policies.5

Bringing Data to the Discussion

So, what’s real and what isn’t when it comes to the politics around abortion? Can we navigate this topic as sanely and as rationally as possible? If so, how? Here at the Skeptic Research Center, we can’t promise to provide answers to culture’s most complex topics, but what we can do is provide context.

We asked 3,014 adults in the U.S. to fill out a 15-minute survey between August 2022 and October 2022. Everyone taking the survey passed attention, response time, fraud, duplication, and bot check. The average survey taker was 44 years old; 46.4 percent of participants identified as White, 32.2 percent as Hispanic, and 21.2 percent as Black.

We polled people on a variety of topics. In addition to asking about their preferred abortion policy (ranging from a total banning of abortion to unrestricted abortion access), we asked them two “accuracy” questions. These questions can help us understand how informed individuals are on the general topics of abortion, and how this impacts their abortion policy attitudes. For example, the number of abortions performed over the last forty-or-so years has steadily declined, but how many people know this? So, the first accuracy question we asked was, “How has the number of abortions performed changed since 1980?”

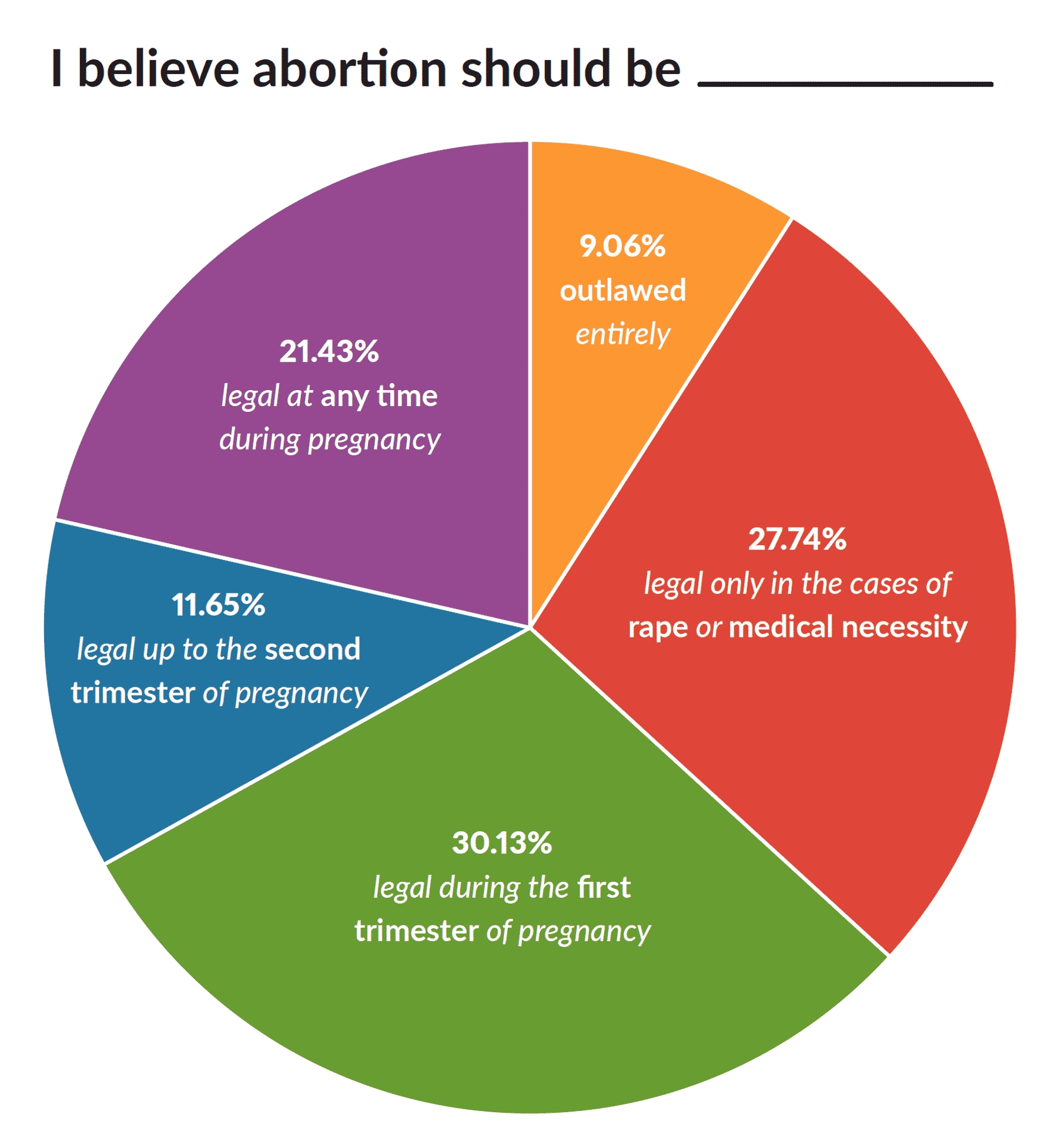

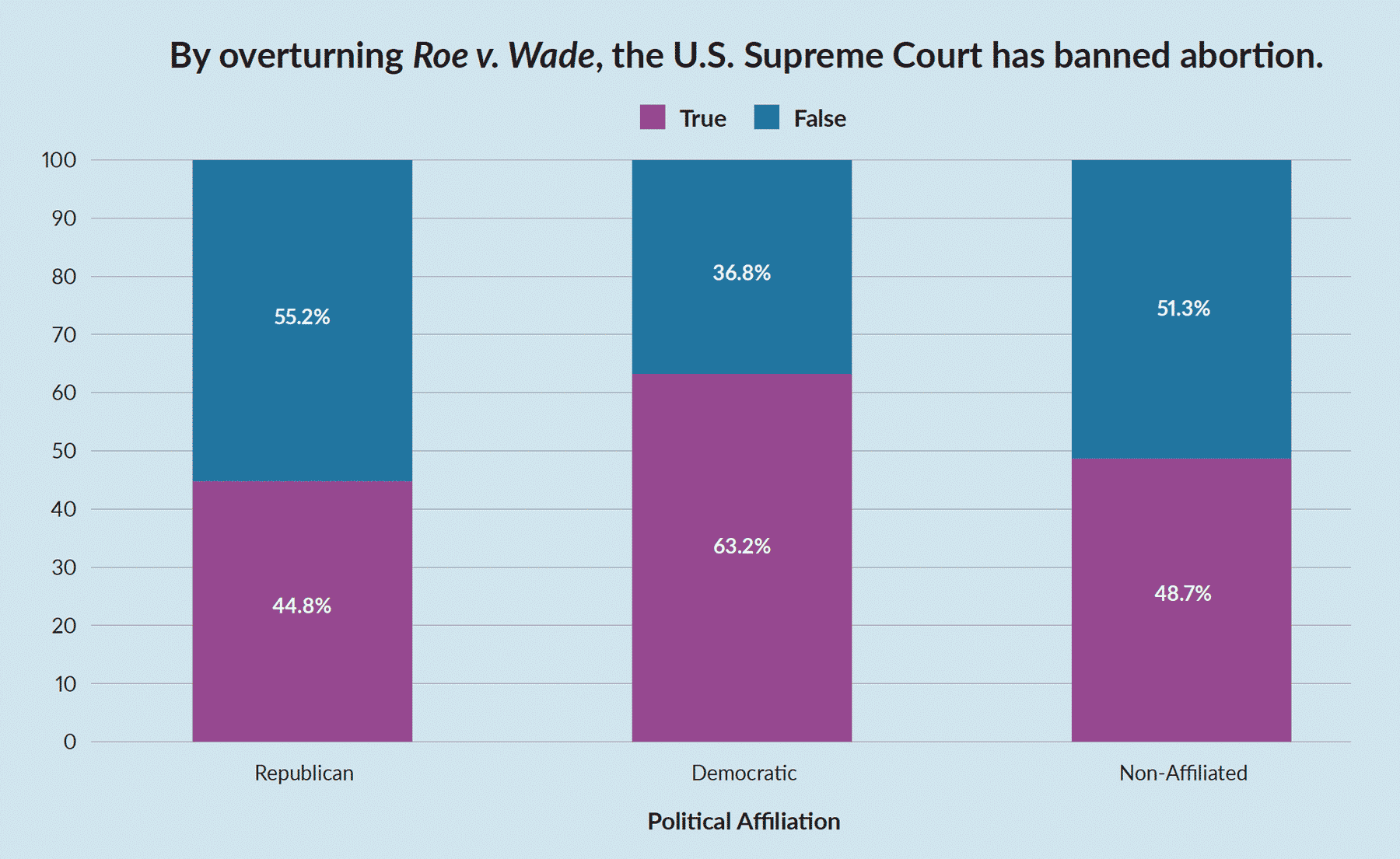

Our second accuracy question pertained to the recent Supreme Court overturning of Roe v. Wade: “By overturning Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court has banned abortion,” with two answer options: “true” or “false.” Of course, the overturning of Roe v. Wade did not ban abortion; rather, it delegates abortion policy to state governments instead of to the federal government.

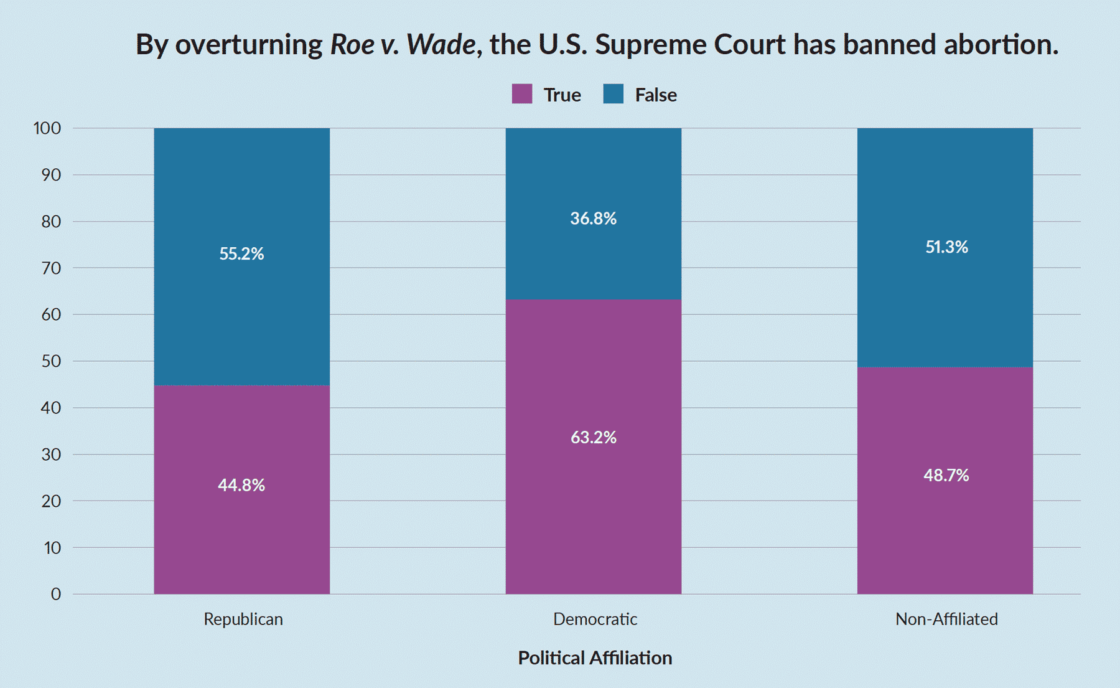

Now, to our results. First, we asked people about which abortion policy they support (see Figure 1). We gave them five options ranging from “outlawed entirely” to “legal at any time during pregnancy.” We found that both extreme positions on abortion are unpopular. For example, only about 20 percent of Americans appear to believe that abortion access should be legal at any time during pregnancy. This is an extreme-left position, given that this could potentially allow the termination of fully viable human fetuses. At the other end of the political spectrum, fewer than 10 percent told us abortion access should be outlawed entirely. This would be an extreme-right position because it would completely strip women of their ability to make decisions about their pregnancy.

While we did find some people holding extreme positions, the important point is that those extremes were not popular amongst most people surveyed. In fact, as seen in Figure 1, the majority of people polled (69.52 percent) either believe abortion services should be accessible to women in cases of emergency (rape or medical necessity) or for any reason up to either the 1st or 2nd trimester. And, again, those hoping to outlaw abortion entirely were a tiny minority—about 90 percent of our sample believed abortion should be accessible to some extent.

Figure 1. Source: Skeptic Research Center. Download full report.

We did, however, find an astonishing degree of ignorance and inaccuracy in our sample. It would seem that the American public is profoundly ill informed on the topic of abortion. For example, half of Americans—regardless of political affiliation—were incorrect about the consequences of Roe v. Wade being overturned by the Supreme Court! (See Figure 2.) Democrats were the least accurate, with only 36.8 percent understanding that overturning Roe did not outlaw abortion. About half of Republicans and political non-affiliates also got this wrong.

Figure 2. Source: Skeptic Research Center. Download full report.

Why are people so confused about the meaning of the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe? Following the Court’s decision, some state legislatures did swiftly enact abortion-ban policies. For example, within 100 days of the overturning of Roe, 66 abortion clinics across 15 states were forced to close.6 Activists in many more states fought to maintain their existing abortion protections, to the relief of many. So, despite the reality that Roe v. Wade’s overturning did not, in fact, mean that the United States Supreme Court banned abortion, it is reasonable to suppose that some people—fearing the worst—mistakenly came to believe that it did.

We also found a surprising degree of inaccuracy regarding peoples’ estimates of the number of abortions performed since 1980. While the number of abortions being performed each year has dropped steadily over the ensuing decades, the vast majority of people believed the number of abortions being performed had been increasing.

In a follow-up analysis, we were able to determine what demographic characteristics were associated with inaccuracy. We found that people in our sample who were younger, less educated, more religious, more anxious, and more trusting of political figures were also more inaccurate about abortion-related topics. Each of these traits, e.g., age, educational attainment, and religiosity, independently correlated with being inaccurate.

Why were these characteristics correlated with inaccuracy about abortion-related issues? There are many probable reasons. Being younger (relative to older) means that most of our reproductive years are still ahead of us, and this might make it more difficult to reason coolly about an emotional topic like abortion. More religiously-inclined individuals may view abortion in moralistic terms and become more anxious about the encroaching sin of abortion access, leading them to overestimate the prevalence of abortions or the sweeping impact of the SCOTUS decision overturning Roe v. Wade. And trusting politicians may be associated with inaccuracy because of politicians’ tendency to overstate or misinterpret facts to further their political agenda.

It is difficult to know for certain why these characteristics were related to inaccuracy on these issues. Most likely, other factors (perhaps even more significant), which we happened to miss in our survey, are driving inaccuracy as well. Our goal is to point in the direction of some of the context on this issue.

Finally, we did something that analysts rarely do—we looked at how accurate people are in their perceptions of one another. What we found was shocking. Democrats told us that they believe almost 60 percent of Republicans want to outlaw abortion entirely, while the actual proportion of Republicans in our sample that wanted to outlaw abortion entirely was only 15.7 percent. Those with no political affiliation told us that they believe 51.8 percent of Republicans want to outlaw abortion entirely. But, most interesting of all, Republicans themselves told us that they believe about half (49.6 percent) of Republicans want to outlaw abortion entirely.

In other words, not only are Democrats and politically non-affiliated people inaccurate about what most Republicans believe on this issue, but even Republicans are inaccurate about what members of their own preferred party think about abortion policy!

How Best to Discuss Politically-Charged Issues

Much more information is available in the full Skeptic Research Center report on abortion, which you can access for free online. The following are a few big-picture observations from our standpoint:

First, abortion is fundamentally a tradeoff. Where does the right to autonomy begin and end? Where does the responsibility of society to protect human life begin and end? These are enormous questions that involve some core components of our collective knowledge, philosophy, and worldviews. Answers aren’t likely to be simple, intuitive, or easily agreed upon.

Second, data and context provide the only intelligent way forward. One must leave emotions out of it. Telling pro-lifers or pro-choicers that they are immoral probably won’t convince anyone inclined to disagree with you. Inevitably, you are more in love with your favored reasons than with the actual details of the counterargument. Looked at from an adversary’s perspective, you have simply regurgitated talking points that their own talking points are designed to rebut.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 28.3

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

How do we get out of this intellectual cul-de-sac? The most promising path would seem to lie in disseminating facts and accurate information. With this report, you can now see which abortion policies Americans tend to support and which they tend to oppose. Most Americans do not embrace either extreme, and what informed debate there is takes place amongst more moderate positions. Additionally, it would appear that our sources of information on abortion are overloaded with falsehoods and inaccuracies. Most Americans were uninformed on the issues about which we asked, and, tragically, they were even uninformed about one another.

What might our national discourse on abortion look like if more people were more informed about the world, the issues at hand, and each other? One might only hope—or one might actually collect and distribute helpful and accurate information! ![]()

About the Author

Kevin McCaffree has a PhD in sociology from the University of California, Riverside. He is an associate professor at the University of North Texas and co-directs the Worldview Foundations Research Team.

References

- Lesthaeghe, R., & Van de Kaa, D.J. (1986). Twee demografische transities. Bevolking: groei en krimp, 1986, 9–24.

- https://rb.gy/x4u7q

- https://rb.gy/7w6vz

- https://rb.gy/7l7pg

- https://rb.gy/1lf5u

- https://rb.gy/d8dar

This article was published on November 15, 2023.