When we think of prominent atheists, we may conjure up an image of one of the “Four Horsemen” of the New Atheism—Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, and Daniel Dennett—authors famous for their steadfast rejection of any form of deity and their willingness to confront the world’s religions. Ironically, however, when we see them in debates and interviews, the confidence with which they make their case and discount the opposition may at times seem indistinguishable from the offputting dogmatism of the hyper-religious. How typical of atheists are the Four Horsemen?

Our research, based on a sample of hundreds of respondents to a survey distributed through social media, indicates that they probably represent a common form of atheism but not the majority view. Most atheists express some degree of tentativeness in their beliefs and would be prepared to consider contrary evidence and arguments. In other words, they are skeptical in their orientation rather than dogmatic. However, the prevalence of dogmatic atheism may come as a surprise to some observers, including Richard Dawkins,1 who stated that he “would be surprised to meet many people” who would say “I know there is no God.” Many respondents in our survey said this.

Distinguishing Between Categories of Atheistic Belief

To categorize the various forms of atheism, it is necessary to distinguish among several closely related concepts.

Formal v. informal meanings of atheism. The term atheism literally means an absence of belief in a deity, as in a theism—without theism. This formal usage broadly encompasses both nonbelief and the explicit rejection of a deity. Nonbelief without any inclination to reject a deity is similar to, but distinguishable from, agnosticism, a term introduced by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1876 at a meeting of Britain’s Metaphysical Society, many of whose members were clergymen, and elaborated upon at a symposium published in 1884 by The Agnostic Annual. Huxley defined agnosticism as the absence of belief one way or the other and the absence of a claim to having any scientific knowledge on the issue:

Agnosticism is of the essence of science, whether ancient or modern. It simply means that a man shall not say he knows or believes that which he has no scientific grounds for professing to know or believe.

Huxley described how he arrived at this position:

When I reached intellectual maturity and began to ask myself whether I was an atheist, a theist, or a pantheist…I found that the more I learned and reflected, the less ready was the answer. They [believers] were quite sure they had attained a certain ‘gnosis,’—had, more or less successfully, solved the problem of existence; while I was quite sure I had not, and had a pretty strong conviction that the problem was insoluble.2

In informal usage atheism usually refers to an explicit belief—or at least an inclination toward the view—that no deity exists. Within this category a further distinction can made between atheists who claim to have knowledge or proof that no deity exists (gnostic position) and atheists who claim that no such knowledge is available and may never be attained (agnostic position).

Agnostic-atheism v. gnostic-atheism. Robert Flint, an influential Scottish philosopher and theologian, advanced a concept of agnostic-atheism in his Croall Lecture of 1887–1888.3 He suggested that the two terms were synonymous and should not be differentiated, arguing that it was possible for an individual both to believe that there is no God and that the question of God’s existence is unanswerable. However, agnostic-atheism clearly differs from Huxley’s agnosticism in that the former includes the belief that no deity exists whereas the latter is noncommittal on the issue. Agnostic-atheism, in turn, implies a concept of gnostic-atheism in which the atheist claims to have proof or knowledge that no deity exists.

From this discussion we may identify three basic categories of atheistic belief:

- nonbelief in a deity without taking any position on the issue;

- agnostic-atheism, expressing disbelief to some degree but without a claim of knowledge (skepticism); and

- gnostic-atheism, firmly rejecting the existence of a deity and claiming to have knowledge or proof that no deity exists (dogmatism). We describe now our research showing that these categories are empirically distinguishable in survey respondents’ explanations of why they do not believe in any form of God.

Survey Methods

Data were collected from several questions included within a larger survey that was developed by the first author for a Master’s Thesis at California State University, Fullerton, on the topic of patterns of moral values among atheists, deists, and theists.

Identifying atheists. A total of 666 participants (a purely coincidental number!), gathered through Facebook and other social media, was categorized according to their responses to six “belief” questions that began with, “Do you believe in a God that…” and then stated a particular trait. Five traits were theistic (e.g., “monitors your behavior,” “intervenes in human affairs”) and one trait was deistic (“created the universe, but refrains from interacting with it”).

An atheist was operationally defined as a respondent who answered “No” to all six belief-in- God questions, thereby meeting the requirements of the formal definition of an atheist. As a check on the validity of this definition, the page that followed asked respondents to indicate if they had a “religious affiliation,” with 11 affiliative options arranged alphabetically from “Buddhist” to “Seventh Day Adventist” (with “Other” at the end) plus two rejectionist options, “None-Atheist” and “None- Agnostic.” It was expected that virtually all of the operationally defined atheists would identify as atheist or agnostic.

Exploring the thoughts of self-identified atheists. A total of 233 respondents selected “Atheist” instead of a religious affiliation and were transferred to another page that presented the question, “Since you selected atheist, would you please elaborate on why ‘atheist’ is a more appropriate characterization of your beliefs than ‘agnostic’? How do you differentiate between these two terms?” Respondents could answer by typing in an open-ended text response (219 total).

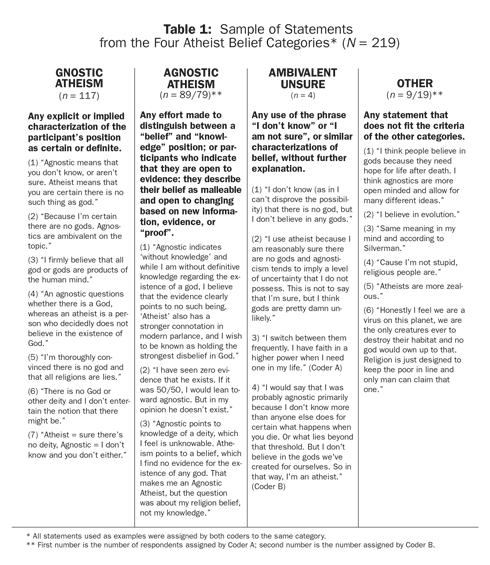

Development of coding criteria. The authors initially created tentative criteria for assigning responses to categories based on respondents’ flexibility of belief and whether or not they made a distinction between belief and knowledge. There were four categories, which in current terms were: gnostic-atheism, agnostic-atheism, ambivalentatheism, and “other” (not classifiable).

The authors independently applied the criteria to the first 50 responses and the level of agreement was assessed statistically (using Cohen’s kappa, maximum value =1) to see if it was greater than the level expected by chance. The value found was .746, which was above chance and would generally be considered to show “good agreement” (.60–.80= “good”, .80–1.00=“very good”).4 After discussion of cases of disagreement, the authors independently applied the criteria to the remaining 169 respondents. The kappa value for all 219 cases was .700. The criteria were as follows:

Gnostic-Atheism: Any explicit or implied characterization of the participant’s position as certain or definite.

Agnostic-Atheism: Any effort made to distinguish between a “belief” and “knowledge” position; or participants who indicate that they are open to evidence: they describe their belief as malleable and open to changing based on new information, evidence, or “proof.”

Ambivalent-Atheism: Any use of the phrase “I don’t know” or “I am not sure,” or similar characterizations of belief, without further explanation.

Other: Any statement that does not fit the criteria of the other categories.

Table 1 shows examples of statements that were assigned by both coders to each category.

Survey Results I: Nonbelievers Who Do Not Reject a Deity

Nonbelief and religious affiliation. Of the 666 social media respondents, 366 (55%) met our operational definition of an atheist (which is also the formal definition) by responding “No” to all six belief-in- God questions. Of those who were operationally defined as atheist, responses to the religious affiliation question were as follows: 306 (83%) responded “None”; 232 (63%) identifying as “Atheist”; and 74 (20%) as “Agnostic”.5

Nonbelievers are thus highly likely to reject a religious affiliation (95% confidence interval: 79% to 87%) but a substantial percentage of nonbelievers (at least 13%) do not reject it. It would seem that one could affiliate with a religion for a variety of social and psychological reasons other than belief in a deity, for example, secular Jews who attend religious services for social or emotional reasons, a family that practices the religion, identification with the religion’s moral values, or the absence of a deity in the religion’s ideology, such as Buddhism.

Defining nonbelief: agnosticism + formal atheism. The lightest shade of atheism in our model is nonbelief without taking a position on whether a deity exists. Respondents who identified as agnostic rather than as atheist would meet this requirement provided that they also responded “No” to all belief-in-God questions.

As noted above, there were 74 such respondents. However, there were 34 additional agnostics who could not be classified as nonbelievers because they did not answer No to all the belief-in-God questions.6 One could not simply go with the agnostic label. Combining it with the belief questions was essential.

In contrast, if a respondent self-identified as atheist, in virtually every case she or he answered “No” to all the belief questions. Beyond the 232 validated atheists, one additional respondent was classified as a deist.

Survey Results II: Nonbelievers Who Reject a Deity

Distribution of agnostic- and gnostic-atheists. The majority of self-identified atheists were gnosticatheists, an orientation that we have characterized as dogmatic rather than skeptical. Table 2 shows the distribution of respondents across these two categories.

Most of the respondents were classified as either gnostic- or as agnostic-atheists (206 or 196 depending upon the coder). Both coders classified 117 respondents as gnostic-atheists (53.4%; confidence interval: 47% to 60%) and classified an average of 84 respondents as agnostic-atheists (38.4% of respondents; confidence interval: 32% to 45%).

The Majority of Atheists are Skeptical, Not Dogmatic

The survey data indicate that most atheists in the sample maintained a skeptical orientation toward their own position and were open to considering evidence and arguments favoring a theistic position. The numbers of respondents in each belief category were as follows:

Gnostic-Atheist, 117;

Agnostic-Atheist, 84;

Nonbeliever (uncommitted), 74.

As percentages of the total (275) the distribution was:

Gnostic-Atheist, 43%;

Agnostic-Atheist, 31%;

Nonbeliever (uncommitted), 27%.

Combining the last two categories, 58% (95% confidence interval: 51% to 63%), acknowledged a distinction between what they believed and what they thought they knew, a precondition for critical thinking and reasoned debate.

Conclusions: Faith-Based Atheism

In demonstrating a sizable category of gnostic atheists, our data reveal a way of thinking among many atheists that is fundamentally religious in nature.

Do atheists accept atheism on faith? In The God Delusion, Dawkins proposed a “spectrum of probabilities”7 to represent the range of judgments that people could make on the question of God’s existence. It is a continuous scale highlighted by seven landmarks: (1) strong theist, (2) de facto theist, (3) leaning towards theism, (4) completely impartial, (5) leaning towards atheism, (6) de facto atheist, and (7) strong atheist. Dawkins characterizes his own position as (6) and “leaning towards” (7). He states that it is not (7) only because, in principle, one cannot prove that something does not exist. It would have to be accepted on faith, and in contrast to believers in God, “Atheists do not have faith…”

However, when we look at the data we find that more than half of atheists who take a belief position express certainty in the non-existence of God, with statements such as “Atheist means that you are certain there is no such thing as god,” “I’m certain there are no gods,” and “There is no God or other deity and I don’t entertain the notion that there might be.” As Dawkins states, “reason alone could not propel one to total conviction that anything definitely does not exist.” What fills the gap here is faith. At the extreme ends of Dawkins’ scale we essentially have two opposing religions.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 22.2 (2017)

Buy this issue

The two shades of theism. The dogmatic and skeptical shades of atheism seem likely to have counterparts on the theistic side of the issue, so that with appropriate defining criteria the methodology we have described here should also reveal gnostic and agnostic forms of theism.

Gnostic-theists would be individuals who equate their beliefs with facts, dogmatically insisting that they have positive knowledge of God’s existence. Agnostic-theists would be individuals who accept the distinction between belief and knowledge, thereby demonstrating a degree of skepticism about their own position, and would indicate that their belief is based on faith, intuition, or an interpretation of natural phenomena. A 5-level, bipolar scale relating theistic and atheistic beliefs would be:

- Gnostic-Atheism

- Agnostic-Atheism

- Nonbelief

- Agnostic-Theism

- Gnostic-Theism

The scale represents maximum darkness at both ends, the domains of dogmatic thinking. Maintaining a skeptical attitude toward one’s own beliefs can be a challenge but, as the achievements of science have shown, it is a better route to enlightenment. ![]()

About the Authors

Brittany Page earned her BA in Psychology from California State University, Fullerton (CSUF). She is currently in her third and final year to obtain her Master of Science in Clinical Psychology at CSUF. Page’s research interests focus on issues related to morality, political psychology, and anti-atheist prejudice. Her master’s thesis is entitled, “Are atheists immoral? Patterns of values of atheists, deists, and theists on moral foundations.” Brittany also hosts the podcast, “I Doubt It with Dollemore” a twice-weekly news and comment show dedicated to all things news, politics, and religion.

Dr. Douglas J. Navarick is an experimental psychologist and Professor of Psychology at California State University, Fullerton. He regularly teaches courses in Introductory Psychology and Learning and Memory. Since the 1970s, Navarick has published research articles on choice behavior in pigeons and humans and is currently investigating how we make intuitive moral judgments.

References

- Dawkins, Richard. 2006. The God Delusion. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 73.

- Huxley, Thomas H. 1894. Collected Essays, New York: D. Appleton and Co., Vol. 5, 237–238.

-

Flint, Robert. 1903. Agnosticism: The Croall Lecture for 1887–88. Edinburgh, Scotland: William Blackwood and Sons, 49–51:

If a man has failed to find any good reason for believing that there is a God, it is perfectly natural and rational that he should not believe that there is a God; and if so, he is an atheist… if he goes farther, and, after an investigation into the nature and reach of human knowledge, ending in the conclusion that the existence of God is incapable of proof, cease to believe in it on the ground that he cannot know it to be true, he is an agnostic and also an atheist—an agnostic-atheist— an atheist because an agnostic… while, then, it is erroneous to identify agnosticism and atheism, it is equally erroneous so to separate them as if the one were exclusive of the other.

- http://bit.ly/2n6HxSy (retrieved 3/4/2017)

- Of the 28 nonbelievers who did not identify as atheist or agnostic, and who responded to the religious affiliation question, the affiliations were as follows: 6 Buddhist, 4 Christian – Catholic, 2 Christian – Other, 4 Christian – Protestant, 3 Jewish, 3 Seventh Day Adventist, 6 unaffiliated (“other”). An additional 32 nonbelievers did not respond to the religious affiliation question.

- 15 were deists (responded “Yes” to deistic trait, not to the five theistic traits), 9 theists (“Yes’ to at least 1 theistic trait), and 10 unclassifiable because they did not complete the belief questions.

- Dawkins, op. cit., 72–73.

This article was published on June 9, 2017.

![Jacques-Louis David [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.skeptic.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/Jacques-Louis_David_The_Death_of_Socrates-2x-1120x737.jpg)

Well, now that we have had a thoughtful thrashing, I would add this one fun thing…

My friend wrote me years ago to talk of a diety.

Noting the spelling, I replied: “Wouldn’t that be the god of weight-watching?”

For the authors

I found the article thought-provoking.

I had a question on the sampling methods. How did you select the 666 (really a coincidence ?!)? The article says from social media sources. Was the attempt to model the US as a whole or was it designed toward people inclined to atheism – random or targeted? I just thought the % of stated atheists at >33% and operational atheist at 55% seems to suggest you are targeting that group. Just trying to understand the method.

Thanks!

Since I subscribe to the simulation hypothesis, where do I fit on the quadrant?

Meh

As one mentioned having so many concepts for God floating around makes these surveys difficult. So let’s just say that we could include any very old intelligence in the universe or before our universe. This is not impossible to imagine. But most Gods would have very low probabilities.

As Doug Hubbard points out people are not very well calibrated until they learn how to estimate quantities with confidences. If I am totally agnostic I might say for me to be 90% certain about the truth of the statement then p(any God) is somewhere in [0,99] % range. I am mostly unknowing. A strong atheist might say with 90% confidence p(any God) is in [0, 0.0001]. The smaller interval demonstrates gnosis as more certain. Each person’s interval is calibrated to what she knows.

When I was a believer I was 90% sure p(my God) is in [90,100]. It doesn’t mean I was well-calibrated. Now it’s p(any God) is in [0,5]. Less agnostic both times. I think this is what the authors were getting at. Not sure what the point to this exercise is though. I also thought these terms were already settled in the past.

Hubbard showed that once a person is trained in estimating 90% confidence intervals for questions like “what is the wingspan of a 747?” And they start being in the intervals 90% of the time, they are calibrated and they can use it in multiple scenarios and the ability to remain calibrated in other estimations will tend to stick with them.

It seems to me that if God really walked the earth as a man, performed miracles, was crucified and rose from the dead, after 2,000 years there would be no scientific proof.

One thing to consider is that in addition to the utter lack of evidence present for any diety/spiritual entity, we also have plausible explanations for why humans would invent diety(ies) and spiritual entities.

As a social psychologist, I can articulate a cluster of theoretically-based reasons (e.g. the problematic nature of existentialism for us, terror management theory [fear of death, not terrorism], need for belongingness, social control, in-group/out-group dynamics, etc.) for humans to construct dieties and organize around those dieties (i.e. build temples/churches, have religious/spiritual rituals, etc.). Having *both* a lack of evidence for the existence of dieties *and* a plausible, theoretically-driven explanation for why humans would construct and organize around them is the reason why I am a strong atheist. This is a scientific, not a dogmatic, position.

You can say I am picking and choosing theories that support my position, conflating belief and knowledge and falling prey to a confirmation bias, and if you are thinking that, then leave me a reply and we’ll collaborate on some research. I’d rather research this question with someone who disagrees with me. These theories are well-established, have bases in evolutionary psychology, and can be tested in this context.

As a scientist, I am disheartened by the use of the word “dogmatic,”

the equivalency of atheism to theism presented in this work, and the way the methods were carried out. While the methodology used is conventional for the type of research the authors are doing (inductive, qualitative), the choice of wording in the presentation of findings is naive and unnecessarily inflammatory, the operationalization of “atheism” is oversimplified and the methods are potentially biased.

Instead of labeling gnostic-atheists as “dogmatic,” why not focus on the intersection of belief and knowledge and leave the label out of it? The authors themselves acknowledge in the introduction that religious dogmatism is offputting. It’s sexy to put labels in the 2×2’s that are sometimes seen in the analysis of results of this type of work, but in this case, the label of dogmatism suggests a negative valence in work that is presented as an effort to illuminate the nature of atheists’ self-categorizations. If I assume this work is a neutral effort at improving knowledge/understanding, why set the stage for both gnostic theistic and gnostic atheistic positions to be offputting?

This is compounded by the use of the “informal” definition of atheism. If the authors had chosen to focus on belief and knowledge, there is no need to use an “informal” definition of atheism, the use of the terms gnostic and agnostic would not be confusing to readers, and the work would at least appear to be more rigorous and neutral. The equation of gnostic athieism and gnostic theism as both religious demonstrates, as others have pointed out, a gross misrepresentation of what theism and atheism are, by definition.

While I’m at it, why not have the responses coded by individuals naive to the research question? The authors stated that during coding they used tentative, pre-determined categories and interrater reliability (Cohen’s kappa) was solid (big surprise). If the model was sound, naive coders would have produced the 2×2 hypothesized. If I really wanna get picky, there should have been no a priori model presented given the nature of the research question. Data should have been gathered, coded by trained (in method, not content), naive coders and emergent themes analyzed; the research question was stated as open, why don’t the methods align with that?

The effect of all of this is that when I read the paper, there is some question as to whether or not the research is biased. This is a problem. Furthermore, it’s either willful, in which case, as some commenters have suggested, the authors hold a theistic position and are taking passive-aggressive jabs at atheists, or they are needlessly stirring a pot and undermining objective discussion about how atheists view themselves. It’s also possible that the research is simply naive and the work needs development in its rigor. Either way, there’s significant room for improvement. I’m kinda disappointed that this article would get so much attention from the Skeptic’s Society with such serious internal issues.

Replying to J. Anderson, Comment 41

You said that there is an “utter lack of evidence” for a deity and that I should leave you a reply if I think you’ve fallen prey to the “confirmation bias”.

Your comment does suggest that confirmation bias is influencing your thinking on this issue. You never addressed my preceding comment (#40) that presents evidence for a non-material, willful influence on natural processes (origin of life).

Perhaps it was just an oversight that you did not see my name there and the heading in caps indicating what the comment was about, but the fact is that you did not address evidence that was potentially in conflict with your own strongly held beliefs. It’s worth considering the possibility that a confirmation bias is present.

How would you assess this evidence in Comment 40?

A QUICK TEST OF RELIGIOUS VS SCIENTIFIC THINKING

Many commenters are saying they would consider evidence supporting the concept of a deity if it was available but it just isn’t there. Maybe it’s there and it’s just not being seen.

In The God Delusion Dawkins stated that he was surprised that chemists had not yet created a living cell from something that was not already alive. It’s now 10 years later, and despite advances in molecular biology, chemists have still not demonstrated that “abiogenesis” really happens, that life could have had a material origin.

Does this continuing inability to demonstrate abiogenesis reduce your confidence in a material origin of life?

If your answer is NO, suppose that another 10 years went by and nothing changed. Would that reduce your confidence?

If STILL NO, then could ANY amount of time reduce your confidence?

If you’re still a true believer, then you may want to consider the possibility that you’re thinking religiously, not scientifically. How would you distinguish abiogenesis from a religious prophecy?

No, no, no! There are not 3 types of atheism!!! There is only ONE type & I can prove it as well! The ONLY sort of atheist is someone who doesn’t accept claims some god exists. That’s IT. That’s ALL. Any additional issues about whether they can really know whether god claims are untrue or not muddies the water. Theists came up with a claim: A god (or gods) is real. Atheists of ANY sort don’t believe this claim. Atheism isn’t any sort of ‘claim’. If you think it IS then is health ‘a type of disease’ or simply NO disease at all? …Well?

YOU might distinguish ‘evangelic Atheist’ for ‘atheist’.

Richard Dawkins and the like see so desperate to make other people ‘not believe in “God” that one suspects that, like Evangelical Christians, they are really trying to convince themselves

Rubbish!

Atheism means “No God” – disbelief in any god or deity.

If a person is willing to consider that there might be a God. then they are correctly called Agnostic — “aka No Knowledge”

I find the whole article highly insulting! No God — no weird whatever anybody means by God.

@Jenny H sez:

“Rubbish!

Atheism means ‘No God’ – disbelief in any god or deity.

If a person is willing to consider that there might be a God. then they are correctly called Agnostic — ‘aka No Knowledge’

I find the whole article highly insulting! No God — no weird whatever anybody means by God.”

Hear-hear! One wonders that the authors don’t get that — or chose not to.

I think a small part of the problem might be that atheism is properly described as the absence of belief in gods, but any number of theists have replaced ‘absence’ with ‘lack’, bringing the false implication that there is something desirable missing. There is not.

One could look at two lumps of gold, and note that one has a streak of lead embedded in it, while the other does not. Do we observe that the second nugget “lacks” a lead inclusion? Or, in context, might we observe that the pure nugget is absent any impurity, while the other is an amalgam? It takes a convoluted – one could say biased(?) – turn of mind to consider the pure nugget to be ‘lacking’ an impurity.

Now bring that latter sort of thinking to concepts like theist and a-theist, and you have the makings of an article in Skeptic. An article that would have benefited (or more accurately, Skeptic would have benefited) from better screening.

A very interesting and useful discussion I hope will be augmented with a more thorough discussion on the shades of Theism. On both sides of the theistic/atheistic spectrum, reasonable people assume there are things that monkey brain 2.0 is incapable of understanding; not because of complexity, we have computers for that, but entire logic systems we can never grasp. The Scientific Method,that wonderful invention of the 18th century Enlightenment , is a discipline that applies only to measurable, observable phenomenon and certainly stops short of explaining what lies outside of our mental realm. Indeed, one has to ask, what sort of scientific evidence could possibly produce a Theistic outcome. The thought process that filters all possibilities through what is measurable, is doomed to produce a very limited world view which sometimes forces us to step outside of scientific reductionism in trying to understand what we are.

You are conflating “what is measurable” (or not) with “what has been measured” (or is yet-to-be measured).

If something can have an effect on the physical world (or the physical human), then it necessarily has a physical component and is ‘natural’. In principle, then, it or its effects can be measured. If it or its effects are _defined_ as forever unmeasurable, then that is the equivalent of doesn’t exist or doesn’t matter.

… angels… dancing… pinheads…

The article has more than a whiff of ‘Well, atheists have a religion, too!’.

No, I don’t.

I do not “believe” in “no god”, I simply don’t believe in claims for which there is no evidence, and my life has suffered in no way as a result.

But to paraphrase Shermer, I’m all for eternal life; just give the me evidence, and I’ll be right there!

I’ll let those who compose the surveys call that what they may. I have no control over it.

I am in agreement with Mathew Goldstein and many others here. Indeed, I take very strong exception to the labeling of my probabilistic/ almost certain belief that there is no god as being dogmatic.

As others have noted, why can’t one have a strong tentative view of reality and yet simultaneously be open to new evidence? Why does my confidence in my tentative but strong view make me dogmatic?

By sticking the “dogmatic” label on overt disbelief in a god, the authors have not only been incredibly unfair but have done a great disservice.

Ditto, well said.

And it is not being dogmatic to say that the burden of proof and evidence rests on the ones making unsubstantiated statements.

@Dr Michael Ecker says:

“As others have noted, why can’t one have a strong tentative view of reality and yet simultaneously be open to new evidence? Why does my confidence in my tentative but strong view make me dogmatic?”

Very well said. Where’s the upvote/like button when you need one?

My opinion, having read the article and having seen some of the follow-on apologetics, is that the entire ‘study’ was based on a presumption and faulty reasoning and the imposition of unwarranted definitional restrictions… FOR THE PURPOSE of supporting the presuppositions. In other words, bass-ackward ‘science’.

Has Skeptic been secretly purchased by that Indian company that is buying up science journals and turning them predatory and antiscientific? Anybody wanna start yet-another conspiracy theory? :-)

Respondents were classified according to what they wrote.

If you had written the phrases you used here:

Probabilistic/almost certain

Strong tentative view of reality

Open to new evidence

you would have been classified as AGNOSTIC-ATHEIST (skeptical), not gnostic-atheist (dogmatic).

We probed participants’ thoughts as expressed spontaneously, without prompting or debate.

For additional perspective on your views you may want to check out my comment listed as #40.

Theists, too, should realize the difference between gnostic theism, which early Christian church fathers fought so fiercely. Isn’t it better just from the agreeableness factor to be agnostic in anything? It is easier than taking a position between atheism and theism. Perhaps being one-day atheist, the next day theist, average the polar opposites and one gets a wishy-washy agnostic!

A lot of posts seem to call out for evidence in a empirical, scientific fashion about theist position. “What’s their proof?” could someone says.

But that seem wrong from the start. How you search then exclude any “meta-empirical” thought and arguments. If you say that empical scientific knowledge is giving you confidence about ordinary knowledge believes, that is a thing.

But if that confidence means that it is only the empirical evidence that is worth believing to, there is always at least a moral assumption that what is “worth” something is emprical thruth alone.

“What should I do ?” is not a question for scientists, when we ask ourselves what is good and what is evil.

Also, keeping the research to empirical evidence exclude existencial thoughts like “why do thing exist ?” “why do I exist?”

Either :

1- things exist by themselves (then it is a irrelevant question) Things happen because … they happen

2- things exist by a cause

Typical philosophical consideration arround “God” as a meta-empirical hypothesis.

When I am asked : do you believe in God?

I ask back: do you believe in Kukuriku?

Most people would ask: what is kukuriku?

My answer is : I don’t know.

Therefore I do not belong to any category mentioned in your article.

To say that one does not believe in god, is admittance of knowing what got is.

Since I have no idea what one means by “god” or by “God” I cannot answer the first question, as stated above.

Whatever believers think that God/Allah/Brahma/whatever is, we do not know — because I have yet to meet a believer who can say what he/she actually believes “god” is, and every believer will tell you something different.

Even if you discover some force/matter that seems to be akin to what some believers have sais “god’ is does NOT mean that you have discovered “God.”

@Arieh Ben-Naim said:

“To say that one does not believe in god, is admittance of knowing what got (sic) is.

Since I have no idea what one means by ‘god’ or by ‘God’ I cannot answer the first question, as stated above.”

In isolation, that comment stands. The trouble with it is that, as long as I can remember, no-one has ever asserted to me that “god exists” without being more than willing to define/describe what they mean.

Not well, mind you, but they always try.

It’s pretty-much impossible to live in society without encountering such definitions. Whether they are coherent or contradict each other or are self-contradictory is a separate question.

I do see any possibility that an anthropic fantasy creates any responsibility on the universe’s part to create a possibility. I think of this to be the Atheist Special Creation Myth. It is just a philosophic dodge to endlessly pursue dead ends and denial of how little what people fantasize about matters.

I also don’t see this as an absence of evidence claim. The evidence is the source of the claim and the incessantly changing and self falsifiable claims of the source.

One thing I think you could do to parse this line of inquiry is to identify ideological atheist as separate from philosophical atheist from epistemological atheist.

They should have started their article by saying “We are defining knowledge as a degree of certainty no one can have about anything. By our definition of knowing you can not know 2+2=4.” That is the definition they appear to be using without saying so.

Search You Tube for “three shades of atheism” for a video about this article and more comments.

Contemporary culture is awash with conspiracy theories, whether Obama’s birthplace, 9/11, JFK’s assassination, Elvis sightings, Roswell, NM or the moon landings. Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary these theories manage to gain traction over time and with an ever increasing population of adherents. The rest of us know these people are wrong and usually find futility in trying to change their minds. Conspiracy theories are therefore false beliefs, the strongest of them held with a religious fervor.

Belief in super natural agency and all the religions that sprouted from it is therefore the world’s oldest, largest and most elaborate conspiracy theory. The conditions that occurred 100, 1000 or 10,000 years ago that gave rise to supernatural explanations for the natural world can be explained by science with exceptional accuracy, yet “believers” gave rise to God(s) and the religious phenomenon via the mental failing which today we call conspiracy theories. Religious belief is therefore a mental failing, often though not always correctable.

Thank you Ann W – succinct and excellent exposition of the deistic narrative. This is already in my rebuttal file.

@Ron

I can tell from your posts that you are one of the intelligent, good-looking ones!

Thanks, Dad!

LOL!

When it comes to the existence of God, there are only two possibilities:

A: God does not exist

B: God does exist

If the answer is in fact A, then that is the end of the matter even if we don’t realize that.

If the answer is in fact B, then there are only two possibilities:

B1: God exists but never interacts with us

B2: God exists and does interact with us.

If the answer is in fact B1, this is a proposition that merely dissolves into Deist fantasy. A god who “never interacts with us” is the same as “no god at all.”

And there is no difference between “no god at all” and “the same as no god at all.”

If the answer is thought to be B2, then it is based on false information because no supernatural being or event ever interacted with us. Not ever. Not from the beginning of time up to the present moment, not from the most minute organism or subatomic particle to the largest galaxy. Not anything. Not ever. Every single phenomenon ever is strictly due to natural causes and no supernatural phenomenon has ever been observed. No supernatural intervention has ever occurred or has been necessary to have attained the natural universe. Not ever. Not even once.

So in summary:

A God (or anything supernatural) does not exist — End of story

B: Something supernatural does exist

B1: But does not interact with us — Same as “does not exist”

B2: Does interact with us — False

If this argument was presented in a formal debate about anything watever , the police would have to be called.

This is because the audiece would start throwing stuff.

There’s something basically wrong with the argument and people respond to this with anger at having be asked to waste their time.

Douglas Hofstadter has

written to exhaustion on this type of verbal banderwhacky.

Alan Ginsberg hs presented the prototype:

Is God holy?

Are You holy?

Is Holy Holy ??

Dr. Sidethink Hp. D.

Yes, brilliant, Ann W.

Except you just killed Santa Claus with one B2 strike.

But like all fakes and human fantasies, he is indestructible.

One thing that has to be considered when addressing the matter of atheism is the person’s upbringing. Did the parents believe and attend religious services or were the children merely sent to Sunday school to get ring of them? Did they reject all religions or just the one in which they were brought up?

The very fact that we are thinking and asking questions indicates something about us that reflects a greater spiritual entity of which we are all a part.

Most of those who have responded claim to be atheists of one kind or other, but are they rejecting a deity that sits in the sky somewhere or the essence that gives us life?

@Barbara Harwood said:

“Most of those who have responded claim to be atheists of one kind or other, but are they rejecting a deity that sits in the sky somewhere or the essence that gives us life?”

Given that we all (reading this) have life, and that we observe countless organisms around us that also have life, how could one differentiate between naturally living organisms with no supernatural component or influence, and organisms that have all the structure and content but require a supernatural “essence” to live?

And if you can answer that, we can talk about viruses….

In other words, if the definition is made sufficiently nebulous, how can one discern between god and no god?

Where does this “essence” live, when it’s not in a living organism? And if it can’t live anywhere but in a living organism, why is it not generated BY the living organism? And if it doesn’t exist without a living organism, what is the point of claiming that it somehow exists in any meaningful way? What is gained? What can we predict from the claim, and test?

As a different approach, we know that the entire world is covered in a thin layer of excrement. We know where that “essence” came from. . .

I discuss this issue of life being material or non-material in my comment below listed as #40.

It is also the focus of my article on “The ‘God’ Construct” that was in Skeptic a couple of years.

God: “Don’t blame me, I don’t exist”

@Traruh Synred sez:

“God: ‘Don’t blame me, I don’t exist’ ”

As near as I can tell, the only ‘valid’ personal reason for wanting a god to exist is to have something to blame for the gratuitous crap of life.

“I wish you existed, so I could punch you in the face.”

What kind of an atheist I am depends on what kind of God you’re talking about.

If you’re talking about a good and powerful (‘all powerful’) God than the experimental evidence is overwhelmingly against it. Call me a plain old atheist — though I have evidence!

If God through so called representatives offer the excuse that “My good is not your” good, then we have another word for that — evil!

If your talking about the Gods of Martin Gardner or Thomas Jefferson, I’m a little more moderate. Such a Gods is unprovable or disprovable as their existence has no consequence. But you could call me an agnostic, but one not much interested in the answer.

After reading the definitions in the study, which are erroneous in my opinion, then I see the results, I can see why they came to conclusions I believe to be wrong. Perhaps it is me, but I see a definite decline in the quality of articles published by Skeptic starting a several years ago.

Was this written by closet theists?

I expect the “atheism is nothing but another religion/belief system” arguments from the local preacher.

Dogmatic? Am I dogmatic that I don’t think evidence for the Easter Bunny or Thor will pop up soon?

I think this is one of the worst articles I’ve had the displeasure of reading on a skeptic site.

@MajorityofOne said:

“Was this written by closet theists?”

The article, as well as the apologetics in response to some comments, draws one unavoidably to that conclusion.

We had long discussions about the “proper” meanings of atheism and agnosticism back in the early 1990s in the alt.atheism Usenet newsgroup. We even did a survey similar to the one described here. What emerged was less than complete consensus, although we semi-settled on the term “weak atheism” to describe the absence of belief in deities, and “strong atheism” as a belief in the nonexistence of deities. For the “strong atheists,” the degree of confidence or certainty was a secondary issue.

Coming to a common understanding of agnosticism/gnosticism was more difficult. We did not use the term to refer to certainty, a position the current article seems to favor. Although some folks wanted to equate agnosticism with uncertainty, it was pointed out that Huxley’s own words expressed near-certainty about the impossibility of ever knowing one way or the other about gods, e.g., “I was quite sure I had not, and had a pretty strong conviction that the problem was insoluble.” Today, while many people use agnosticism to mean “I currently do not know or am not certain,” some self-described agnostics follow Huxley’s strong conviction that there are some things that we will never have knowledge of or be certain about, and God is one of those things. Agnostics can therefore be very dogmatic.

Another important wrinkle in this, totally ignored by the current article, is that “God” means so many different things to different people. Given the multitude of conceptions of gods, when someone asks me if I believe in God, I ask “which one?” I can be dogmatically certain that some gods do not exist because their descriptions are logically self-contradictory. Others I might be simply a-theistic about because I haven’t been presented with any good reasons to believe. The most difficult version of God to discuss is the undefined, hypothetical one, as in “Might there be some sort of God that has not been described yet?” Given that there might be some highly-evolved, super-intelligent and powerful beings in the universe who would seem godlike to us, I might affirm the possibility of a hypothetical god. Then the person would say, “A-ha, so you are not really an atheist!” Then we go back to playing games with definitions.

I regard myself as an agnostic atheist, as depicted on the representation of four quadrants from two axes.

Gnostic atheist – absolutely certain no gods exist, nor could exist; brooks no doubt on the matter

Agnostic atheist – has no belief in any gods, with a level of confidence (when questioned) ranging from relative indifference to a confidence level of ‘many-nines’ after the decimal

Agnostic theist – believes, on balance, that there probably is a god, but does not claim certainty – ranges from “hedging one’s bets” (Pascal’s Wager), to very high confidence that could be shaken, but isn’t likely to be

Gnostic theist – absolutely certain that a particular god exists, and would not even entertain the possibility of being wrong

This piece takes a theoretical and semantic approach, but many people probably approach the questions more pragmatically and empirically. They have been presented with many religious arguments and have found no substance in any of them, hence see no practical need to consider an obviously remote hypothesis that some sort of gods exist. There is little practical significance to the attitude that gods may exist – you can’t make burnt offerings or human sacrifices to hypothetical gods.

Of course there may be a tribal element in any characterization. Religious belief is very rarely arrived at by an intellectual process. It is almost entirely social, produced by indoctrination in most cases.

The problem with discussion of atheism/theism is that it is an intellectual exercise that does not engage with why people believe one thing or another. Now I understand that that is tantamount to saying that “God” is not the central concept in religion, but I can go with that. On the basis that belief actually comes before the rationalisation of explanation, surely it would be more useful to explore the dynamics of belief, which means, it seems to me, to involve the question of why some beliefs give you a good feeling and why some give you a bad feeling. Religion seems to be focussed mostly on generating good feelings. Which would you choose, good or bad feelings, especially if you did not have the benefit of sufficient scientific knowledge to sift through the related beliefs? There is perhaps a hint here that religion has, or has had, an evolutionary role in helping one feel good no matter what.

I think the general rationale for religion is to control. Therefore it presents persuasive reasons to experience bad feelings, and then offers its ‘out’ to evade the fearsome destination (stick and carrot). Avoiding pain and fear is generally more motivating than seeking pleasure and good feeling.

That’s why [at least some] religions don’t rest on the enticement of life-after-death, but add the additional motivation of a place of lasting punishment and horror that can be avoided if one complies with – insert list of rules, here -…

To bring up a classic example, is it dogmatic to be certain* that there’s no teapot in orbit about Mars? Just because people can imagine something and put that imagining into words, doesn’t mean we have to take it seriously as a a real possibility.

*Recognizing ‘certain’ in the common usage, as simply very high confidence. Otherwise, there would be no occasion to use the word at all.

bingo

“Recognizing ‘certain’ in the common usage, as simply very high confidence. Otherwise, there would be no occasion to use the word at all.”

Excellent point. My sentiments, expressed.

I might adopt the confidence notion, in place of my ‘operational assumptions’ that I’ve been using in discussions with theists and the religulous.

It seems to me that discussions about atheism are really requests to listen to /support someone who has reason to want to confront you in this matter.

the correct answer is

“Why do you ask ? ”

The BEST response you should want is something like

“Buster done told me you was a commie sheeny ”

Actually , the best answer is

“beats me .. how about them Rockies this year ?? ”

Dr. Sidethink Hp. D.

My confidence that there is no god is equal to my confidence that a ghost is not seated next to me, a sprite is not buzzing around my computer and slowing down my Internet, a giant cyclops is not hiding in the woods outside my window, and there is no falling snow in my town on June 21, 2017. It is quite reasonable to draw hard conclusions on all of these matters and stand by those conclusions without suffering a smidgen of doubt.

At some point, you need to review the facts on hand, lay your money down and go about your daily life. I didn’t fall to my knees in prayer today and I didn’t wear a winter coat; I’ve concluded that there is no god, and that it is not snowing today in my town, so no need for contingencies. No reliable evidence to the contrary exists.

It’s confounding that some skeptics are so careful about providing religion and other backwards beliefs with a lifeline by hedging about whether any opinion, point of view, or belief can be 100 percent absolutely proven or dis-proven. No such proof actually exists for anything. A case that is closed can be reopened at any time, as long as there is compelling evidence to do so. Meanwhile, we shouldn’t be afraid to close a case.

There is a singular issue on the wording of certainty. Given the evidence or lack of evidence of a phenomena- for example gravity.

“Are you certain that gravity exists?”

Yes. As the model stands I’m certain of it.

“If you were introduced to a rational evidence based new model that contradicted this certainty would you change your mind?”

Yes. I would.

“Does our certainty in any way mean we are religiously dogmatic about the science of gravity?”

Until introduced to evidence that contradicts it we may say we are certain but we may change.

Certainty as presented in the study doesn’t seem to be accounting for this.

This is not an either or situation (A=B) I’m certain there is no deity therefore dogmatic, it is a conditional paramater (A=B when C [evidence or lack of evidence], if when D [new compelling valid evidence] then A not =B) I am certain there is no deity because there is no evidence for it, however if new evidence were presented then I could change my mind.

People not completely familiar with the scientific method and jargon probably are not aware that they are being dogmatic when they say with certainty that things without evidence do not exist, such as leprechauns, unicorns and gods.

@ Gabriel

The utter absence of any reason, no matter how slight, to believe in leprechauns is absolutely fatal to entertaining the idea that they might exist.

I do admit I enjoy the image of your drifting through reality not knowing if the Easter Bunny is real or not. I bet you’re a trip walking through the park shying away from dragon holes.

At issue here is the psychological tendency of different individuals to accept or not accept a particular idea. Some people are, for whatever reason in their biochemistry or childhood experiences, prone to belief in a god. Others are not so predisposed.

The differences between them are no so much a question of evidence as of how their brains are canalized. People of a mystical bent will believe in some sort of supernatural factor. People without a tendency to mysticism will not. Neither is likely to be swayed by evidence, though both think they are.

Research should be done on why the tendency to mystical thinking exists and what can be done to prevent or cure it. Alleged evidence for or against the beliefs is irrelevant.

I am a second order atheist. James Randi adorns my wall. It is an enlarged picture of him from the back of Flim-Flam. The picture is pretty small, so the enlargement is a little garbled.

I keep the folks who would convert me at bay by saying “I am atheist”.

I like most of those folks. I do not want to offend them. There is little chance though that they are going to look at the conundrums and grasp why it is I can neither prove nor disprove the existence of god. Saying I am an Atheist, lets them see me in a tower that they at least sort of understand. They can see the tower anyway. They can see the rocks coming off the tower in response to the rocks they throw at the tower.

Agnostics are out in the field exposed and seem like viable targets. We run around trying to avoid the rocks being thrown at us, but it looks like we are running towards someone when we do.

@Ron — Perfectly said.

We have to be wary of creating new deities when we get sarcastic. Most of the people in the center are much more worried about the beer at the end of the day than they are the wrath of any god.

I can wholeheartedly concur wit J. Gravelle. Keep it simple. As he stated, the problem started with Huxley and others who opted out of taking a stand and tried to obfuscate his atheism to spare him being “burnt at the stake”. Huxley employed “Pseudointelectual BS” to extricate him out of the fix, and although intellectually stimulating, we are perpetuating this nonsense with above studies and commentaries.

On a further note and a pet peeve of mine: Nobody in his sane mind are going to do this exercise with Pastafarianism (The believe in the Flying Spaghetti Monster) because we know who invented it.

I therefore refuse to be labeled or be associated with any base construct I don’t even accept!

People can label themselves as deists and pastafarians all they like, just don’t call met an atheist or apastafarian. I just plain and simple do not accept such a construct.

I am a completely-convinced and certain atheist for reasons which I can articulate. I harbor no doubts or equivocations.

Yet at the same time, I think it would be ridiculous to say that I would never consider any evidence to the contrary. In fact, I seek out such “evidence” to sharpen the grounds for my convictions.

I have never encountered any evidence that I could not successfully refute, and I confidently expect that I never shall.

It is absurd to say that my willingness to explore new evidence somehow makes me not an atheist.

I am like a Darwinian evolutionist who has never encountered any evidence that Creationism is true, and who confidently expects that no such evidence will ever materialize — but who nevertheless examines with an open mind any fossil which is claimed to refute Darwinian evolution.

Let me add that “arguments” are not evidence, and can safely be dismissed except for entertainment purposes.

The foundation for my own certainty does not depend on “argument” either.

I know that no supernatural beings or events ever existed for the same reason that the authors themselves know that Dumbo the Flying Elephant ever existed.

This flawed article is yet another lame effort to promote the position that hijacks the status of “atheist” while ducking the heavenly consequences of offending the god they still secretly believe in.

It’s not so much fence-sitting as edge-clinging. “I know God will forgive my manly doubts considering the really bad reasons to believe in Him,” they secretly reason, “but I don’t think He will forgive a direct, in-your-face assertion that He does not exist. And his powers of punishment are awesome — so I’ll just waffle on this one.”

I think you may have missed something. If you are willing to consider evidence, then that gets you labeled as an agnostic-atheist. It doesn’t get you labeled as “not an atheist.” You’re still an atheist, and there is no shame attached to your willingness to consider evidence. You still get to claim you’re an atheist.

A second point: you don’t refute evidence, you explain how it fits within your world view. What you refute is arguments concerning said evidence. If the evidence turns out to be false, it’s not really evidence at all.

@ Ken

My willingness to evaluate new evidence — my eagerness to have that opportunity — does not make me an agnostic-atheist.

For one thing, I’m a hard atheist, not an “agnostic-atheist” — even assuming that such an expression has a meaning, and using the term as this article does. That is, I flatly deny that anything supernatural does exist or even can exist. AND I delight in examining all purported evidence to the contrary.

Refusing to examine any such evidence would be just ridiculous, and a bad sign of the strength of my convictions if they can be so easily threatened. Not to mention that only morons think they can make evidence to the contrary go away by closing their eyes.

Furthermore, if (unimaginably) the evidence turned out to be unassailable and definitive, I would naturally have to re-assess my Darwinian timeline — oops, sorry, I meant “my cosmology.” But like any scientist, I confidently expect that no such evidence does exist or can exist.

So bring it on, and allow me the pleasure of demolishing it.

And for another thing, these agnostic-atheist/gnostic-atheist neologisms are absurd. That’s another reason that being happy to examine any purported evidence that contradicts my convictions does not make me an “agnostic-atheist.” It’s because it is an absurd designation.

May I ask you what word you use to describe a person who is undecided about the existence of God?

I claim to be a probabilistic atheist based on probabilism, the philosophical doctrine that probability is a sufficient basis for belief and action since certainty in knowledge is unattainable.

I prefer probabilistic rather than agnostic or gnostic that result in epistemological arguments.

I place the disbelief in the existence of a god based on the state of being probable. Given the claims attributed to the deity, the lack of empirical evidence to support the claims, and the requirement of deity deemed unnecessary in the material world, the likelihood of some god existing is unlikely to warrant any concern.

I’m with Matthew Goldstein. When gnostic-atheism is defined as “Any explicit or implied characterization of the participant’s position as certain or definite”, and agnostic-atheism contains, “participants who indicate that they are open to evidence: they describe their belief as malleable and open to changing based on new information, evidence, or ‘proof.’ “, they’re not mutually exclusive. Let’s just look at a few other knowledge claims as examples.

I am certain the Earth revolves around the Sun. However, if somebody showed me convincing evidence to the contrary (and it would take a hell of a lot of evidence at this point), I could be convinced to change my mind.

I am certain that the American Revolution took place in the late 1700s. However, with sufficient evidence, I could be convinced to believe that all of our history books were wrong.

I am certain garden fairies don’t exist. However, I could be swayed by convincing evidence.

As long as we’re using language in the normal way, ‘certain’ just means very, very high confidence. And there are lots of things were reasonably certain about, but could be convinced to change our minds on given sufficient contrary evidence. But for some reason, out of all the mythical and imagined possibilities dreamt up by humans, gods get treated differently, and saying you’re reasonably certain they don’t exist gets you labeled dogmatic.

Well, I’m glad that there are no value judgments being made here. (“Dogmatic”, anyone?)

Modern science works based on confidence levels. The more evidence one adduces for a particular view, the more confidence one has in it. At a certain point, we use a shorthand and say that something is proven when the chance of its being wrong is 0.000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001. In practice, that works out just fine.

Sorry, but for any non-trivial issue of reality, levels of confidence are all you get. As the old saying goes, if you want proof, study Geometry. (And, as a ex-mathematician, I’ll warn you that there are issues there, too.)

You may feel that’s not staying a true skeptic (“Well, you didn’t *prove* it!”), but that’s a poor use of the term “skeptic”, which, to my mind, should be reserved for situations where there are reasonable odds of different answers being true. Being skeptical when there is overwhelming evidence for a given viewpoint and overwhelming evidence against other viewpoints isn’t being a good skeptic. It’s being an anti-vaxxer.

In terms of a belief in deities, given that the universe has operated according to physical law from, at the worst, a few microseconds after it began (or after this cycle began), one has pretty good evidence that all-powerful mythological beings aren’t running rampant. If you want to call that kind of logical thinking “dogmatic”, then I guess I’ll have to accept that label.

Well said!

how about (0.000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000t00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000)to the power 0.000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

?

rjp

“Most atheists [as opposed to the Four Horsemen] …would be prepared to consider contrary evidence and arguments” –

– Do you really think that Richard Dawkins or Daniel Dennett would not consider contrary evidence?!

The whole problem is the scarcity of such evidence, or, to put it bluntly, its non-existence. PLEASE deliver the evidence and any true scientist or philosopher will of course consider it.

Arguments in favour of God, such as they are, have of course been considered and discussed, both by Dawkins and by atheists long before him. It is exactly because of these arguments, or their weakness, that people like Dawkins arrive at their atheism. There is nothing dogmatic about such position.

“…when we look at the data we find that more than half of atheists who take a belief position express certainty in the non-existence of God, … At the extreme ends of Dawkins’ scale we essentially have two opposing religions. ” –

– I cannot understand how one may propose any kind of similarity between a rationally adopted, thought-through position based on careful consideration of arguments and logic, and religious faith. Such a proposition is in my eyes an insult of reason. If the complete absence of direct evidence and the weakness of arguments in favour of God’s existence lead one to a logical conclusion that there is no valid reason for believing in God, and, therefore, the only logical position is being reasonably certain of His or Her non-existence (as certain as it is possible to be certain of anything in this world), how on Earth can such a position be equated with faith?

I should not jump to conclusions here but the only plausible explanation for such propositions that comes to my mind is that this is one way in which believers might like to defend their beliefs, that is, by equating them with the atheists’ position. “It’s all just a matter of faith!”

No it is not.

In The God Delusion, Dawkins wrote that he was surprised that chemists had not yet created a living cell from something that was not already alive. That was 10 years ago. With advances in cellular biology and biochemistry since then, he should now be even more surprised.

Question: wouldn’t the continuing inability of chemists to demonstrate “abiogenesis ” count as evidence (not proof, obviously) against a material origin of life? If you’re open to evidence, this should count for something and at least lower your confidence in a purely material explanation of life.

Douglas Navarick asked,

“Question: wouldn’t the continuing inability of chemists to demonstrate “abiogenesis ” count as evidence (not proof, obviously) against a material origin of life? If you’re open to evidence, this should count for something and at least lower your confidence in a purely material explanation of life.”

The more interesting question would be, should chemists ever create life in the lab, how many people will become atheist?

I like Dawkin’s seven grades of belief. I would categorize myself as a 6+. That is, I think the statement “there are no gods” describes all the evidence I know, but if some new evidence were discovered, I’d consider it.

I second this statement.

Huxley be damned for muddying the waters, and condemning generations of us to waste our breath re-re-re-educating people on the distinction between a-/gnosticism and a-/theism.

I long for a formal survey that simply asks “Are you a theist?” and casts each response that isn’t “Yes” (including every “No”, “I don’t know”, and insipid “let me explain my unique pantheo-deism concept” monologue) into the “Atheist” tally column.

In that scenario, I suspect the ranks of our infidel/apostate brethren and sistren far exceed even those recent optimistic projections from our friends at Pew Research.

Howzabout we focus on that which unites our ranks in lieu of whatever dis-similarities which may only serve to marginalize…?

-jjg

Many people are epistemologically unsophisticated and this is a problem. How we justify our beliefs is important, it makes a difference apart from what our conclusions are, and it also affects what our conclusions will be. Too often atheists justify atheism weakly/dogmatically, for example by declaring that anything that is true is automatically naturalistic by virtue of its being true so atheism is merely an axiom. I am convinced that Richard Dawkins adopts a best fit with the evidence based approach when he decides in favor of naturalism. If you would place him in the gnostic category then, given how you are defining gnosticism, I think you are making a mistake.

Where opinion ends and knowledge begins can be a fuzzy boundary. My perspective is that there is a meaningful distinction between supernatural and natural explanations (altough again, there is a fuzzy boundary problem), our successfully tested modern knowledge about how our universe functions rests exclusively on naturalism as both the type of methods utilized to acquire that knowledge and the type of conclusions reached, and this is powerful evidence that we live in an exclusively universe. Lots of scientists are theists and I conclude that this is because theism is psychologically compelling, not because they have a compelling counter-argument for abandoning supernaturalism in the workplace. I concede that our evidence is necessarily limited in time and place and even that the evidence we have could be misleading. Yet I think the evidence for naturalism over supernaturalism has been so persistent and consistent that the probability that new evidence in the future will change the overall best fit conclusion to favor supernaturalism is small. Given that total, perfect, absolutely knowledge is impossible, and given the successful track record of following the empirical evidence, it seems to me that the evidence we already have is sufficient to be confident that metaphysical naturalism is true, and I think everyone today should be an atheist. I am committed to an empirical evidence based approach to reaching conclusions about how the universe functions, and I am convinced that naturalism is indisputably the best fit conclusion.

Naturalism is not as solid a conclusion as macro-evolution because the conclusion is more general, so general that there is no group of people that qualifies as “the experts” for deciding. But the supporting evidence is also substantially larger in quantity since it encompasses all evidence that could be more consistent with supernaturalism than naturalism but is not, and all evidence that is more consistent with naturalism than supernaturalism, not just biology, biochemistry, geology. When the empirical evidence speaks we are obligated to acknowledge and respect what it says. So am I agnostic or gnostic?

Based on everything you said, that evidence bears that there is no God(s), I would say that you’re a Gnostic atheist. There isn’t any shame in holding a strong belief. In fact, some would argue that it’s human nature to believe in things.

It’s also important to remember, that atheism isn’t just not believing in a supernatural God as mankind has defined deities, but not believing in a manifestation of god beyond our comprehension as well. And the concept of ‘beyond our comprehension’ is important as it’s impossible to prove something we can’t form a concept of doesn’t exist.

Therefore, true agnostic atheism means that it may exist. A ‘god’ could exist but based on the evidence we suspect it’s not so, not impossible, but highly unlikely. It’s frustrating that with all we know there is such a paramount question we don’t have a straight answer to. But we don’t have an answer, and that’s a crucial distinction.

The concept of “beyond our comprehensive” as a justification for disregarding the available evidence when reaching conclusions is special pleading. It is a fallacious catch-all argument that can be deployed in any/all contexts to overrule the best fit with the available evidence conclusion. The possibilities are endless, so citing mere possibility is vacuous and cannot properly justify a conclusion. Proper belief justification is all about probabilities, certainty in some ultimate and total sense is impossible and thus is nonsensical as a standard.

Brittany Page and Douglas Navarro are overloading their definitions of agnostic and gnostic that link together multiple concepts which are actually separate. It appears that the main concept that they are trying to capture is empiricism and I think they should characterize it that way instead of agnosticism/gnosticism. It is both true, and important, that empiricism, properly understood, has a built in uncertainty. So by this criteria, under their terminology, I am pretty sure that I qualify as agnostic, and I sometimes characterize myself that way, because I am an empiricist. But empiricists are obligated to reach firm conclusions when the evidence warrants firm conclusions (the available evidence is numerous in quantity, diverse, consistent, etc.) and that is why the agnostic/gnostic distinction can be misleading.

People who are saying “I [do not] believe” are being labeled as gnostic atheists. But their use of the word “belief” to characterize their atheism is fully consistent with their being agnostic atheists. The available evidence is not absent or ambiguous on this question. The available evidence decisively favors no gods. So at least some atheists who firmly believe there are no gods do so because they respect the evidence and follow the evidence wherever it takes them, not because they adopt a closed minded approach. It does not sound like the authors of this study share this perspective about what the available evidence communicates and as a result I think they are over counting the gnostic atheists.

Mathew Goldstein says: “their use of the word “belief” to characterize their atheism is fully consistent with their being agnostic atheists.”

(1) It is not fully consistent. They don’t just use the word “belief”; they say or imply that their belief is certain. Agnostic-atheists do not express certainty; they show a degree of tentativeness.

(2) For the gnostic-atheist, belief and knowledge are one and the same. Belief represents fact, like with gnostic-theists (Table 2). Because they equate belief and fact, there is no need to mention knowledge as a separate issue. Therefore, in many cases the claim to positive knowledge is implied rather than formally stated.

This is supported by comparing the 117 respondents in the gnostic-atheist category with the 4 respondents in the ambivalent-unsure category (Table 1). If respondents expressed a belief without mentioning evidence, they were 30 times more likely to express certainty than tentativeness. Certainty was a marker for a claim of positive knowledge.

It’s possible that if gnostic-atheists were challenged on this point, many would concede that they can’t know for sure, but raising the issue of evidence changes the situation. It’s not how they usually think about it. An advantage of the open-ended text method is that it minimizes artifactual prompts.

In contrast to gnostic-atheists, agnostic-atheists mention evidence WITHOUT PROMPTING, indicating that they recognize the separation between belief and knowledge and this is how they usually think about God.

This article and the first handful of comments here are…quite stupid.

Agnosticism has NOTHING TO DO WITH “belief” (theism or atheism). Agnosticism pertains to KNOWLEDGE. An ‘Agnostic-Atheist’ is one who both lacks (direct) knowledge of God and says so (as opposed to many who also lack such knowledge but claim otherwise) and also lacks belief in God’s existence.

My f***ing word the country has spiraled into massive ignorance in the last 10 years. Does anyone know or remember what Strong and Weak atheism and strong and weak agnosticism are anymore?!

Most constructive comment here….

Exactly!