“To fail as a poet is to accept somebody else’s description of oneself.”

“When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.”

Like most writers, I exact my revenge upon the Pitiless Universe by pressing its most chaotic intrusions into the service of story. The useless death of my car’s transmission, say, finds fresh purpose as a plot device to keep Frank Everyman in Lonelytown long enough to fall for Miss Adventure. The annoying tic of that adjuster denying my insurance claim gets redeployed as the poker tell of a disgraced CEO tossing his dad’s Rolex into the pot. But making the world right through story isn’t always fun and games. We writers have a responsibility to get it right. Which is why I’m so vexed about what to do with Jordan Peterson. I fear he’s beginning to look like a character who doesn’t know what story he’s in.

Before the YouTube and podcast phenom that goes by the brand name Jordan Peterson was dubbed “the most influential public intellectual in the Western world right now,” by New York Times columnist David Brooks (quoting Tyler Cowen),1 there was Jordan Peterson, the obscure if yeasty University of Toronto professor of psychology who taught a popular class based on his then little known book Maps of Meaning. These increasingly appear to be distinct creatures, though one clearly gave rise to the other.

I began to hear about Peterson during his metamorphosis from the latter to the former, when his one-man storming of the ramparts of Canadian PC culture, a cause for which he appeared fully prepared to martyr himself personally and professionally, began to make waves beyond the campus. To the surprise of many, his irresistibly YouTubeable confrontations with transgender rights activists and subsequent television interviews, in which he likened identity politics to “murderous Marxist ideology,” resulted not in his relegation to obscurity, but in a brassy new international platform. And if what I witnessed at the Fred Kalvi Theater at the end of June is any measure, he has put it to extraordinary use.

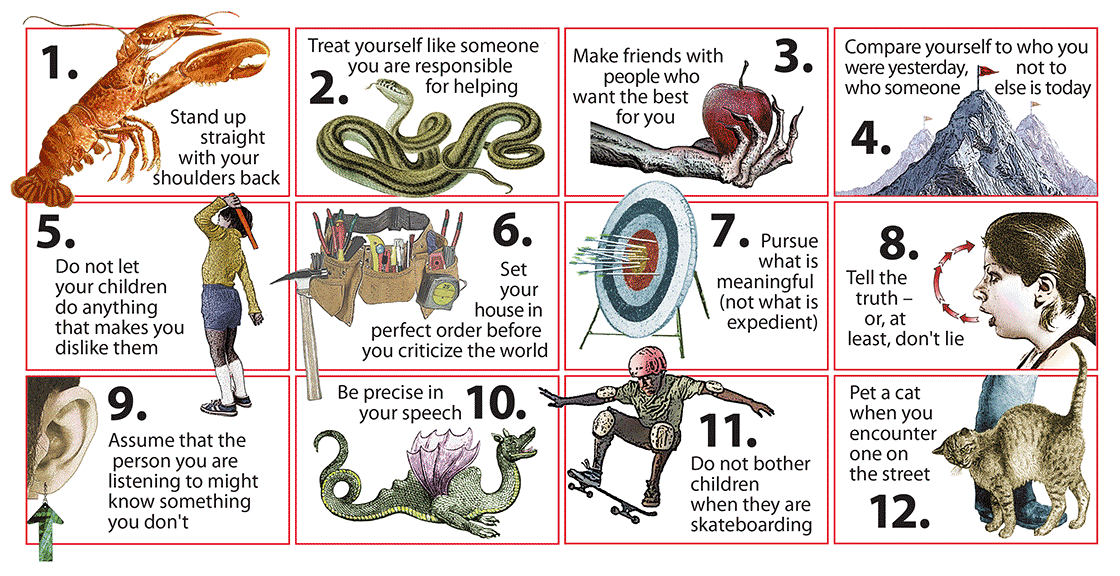

But I don’t want to get ahead of myself. I first want to tell you my impression of Jordan Peterson before he told his Patreon supporters that he feared he would lose his tenure, to which they responded to the tune of $80,000 a month. Before followers from around the world began to (a) proclaim their deep reverence for the transformational power of his lectures and (b) mercilessly troll anyone who didn’t. Before his recently published bootstrapper’s hymnal 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos became an international bestseller spawning what his people call a “live tour”. Before the infamous Cathy Newman interview2 that convinced his detractors that a cordon sanitaire must be established around the dangerous ideological vector Peterson personifies.

I should probably tread lightly here, because these days in polite circles one does not simply express positive opinions about Jordan Peterson. You have to pre-apologize by way of caveats, extenuating circumstances, special pleading, etc. I fear I may resort to all of these before this article is finished but back then, when I began to listen to Peterson’s podcasts and YouTube lectures, he struck me mostly as a rather brilliant-ish fellow who had given a great deal more thought to what constitutes a life worth living than most, and had come up with some answers that he felt were worth sharing. I want to like him, and so should you. Anyone who travels far enough on a narrow enough road becomes an interesting human being because they will eventually come to a place where few others are.

And now, because I’m polite by nature, I feel the urge to apologize for the previous positive statement by pointing out that many of the answers Peterson provides are unfalsifiable assertions or outright speculation presented as common knowledge or as founded upon allegedly inescapable Darwinian realities. But again this was back then, and back then I was perfectly willing to listen to Peterson being wrong, or even sometimes not-even-wrong, and not because there was no stigma attached, but because he could be terribly, frighteningly right in nearly equal measure.

I suppose I’m predisposed to liking Peterson because we share a fascination for the power of narrative. This was the initial appeal of his Maps of Meaning and Psychological Significance of the Bible lectures series. For similar reasons I remember having been smitten with his myths-as-vessels-of-transcendent- wisdom predecessor Joseph Campbell. Bill Moyers’ 1988 miniseries Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth gave me a revelatory new way to look at story. Unfortunately it did the same for every development executive in Hollywood. In the 1990s, the beats of Campbell’s monomythic hero’s journey became the stone tablets of blockbuster moviemaking. Studio corridors rang out with cryptic comments like, “I get the whole water world concept, but how could the Costner character possibly meet the mentor before he refuses the call?”

And what about Peterson’s personality? I spent the better part of an hour in the green room with the subject in question, along with Skeptic publisher Michael Shermer, and as much as I might like to report back one or two obligatory journalistic demystifications, what I got was the close-up version of the same person I’d seen in those YouTube lectures — the pensive gaze, the passionate delivery, and more quintessentially, that earnestness that seems so lost in time that it might have come from another era. If Peterson’s abrasiveness is upsetting, his public displays of tenderness and empathy are downright unnerving. The man has to be the most unlikely celebrity intellectual since Fulton J. Sheen’s blackboard lectures on everything from “how to psychoanalyze yourself,” to “how to think,” had 30 million viewers a week saying later ‘gator to Uncle Miltie back in TV’s first golden age.3

All of this got me thinking, if I were to write Peterson into a novel, how would I portray him? What would he represent? What is his significance in our time? More than a throwback to modernism, it’s as if he is channeling a kind of Edwardian eccentric. The practiced certitude, the testiness when challenged, the relish and sheer, no, manic energy he brings to his role as messenger of revealed truth, it’s all so reminiscent of a certain type of iconoclast that emerged more than a century ago. If you want, think of them as a new wave of meaning makers that arose as a reaction to the increasing uncertainty of the industrial age.

At one end of the spectrum might be a maverick like John Harvey Kellogg, whose Battle Creek sanitarium promised heaven on earth by way of daily enemas and a stentorian adherence to personal hygiene. At the other end of the spectrum is the idiosyncratic trickster Aleister Crowley, who carefully nurtured a reputation as the “most wicked man in the world.” Somewhere between the two are the likes of G.I. Gurdjeiff (Armenian mystic), Alfred Korzybski (general semantics), and Helena Blavatsky (Theosophy).

Parenthetically, the fact that I’m writing here for a skeptical audience is not lost on me. I know that these counterculture figures have been dismissed as either sadly deluded spiritual seekers, mischievous cranks, or even less generously as brazen hucksters peddling their tacky esoterica as secret knowledge. But every skeptic worth their salt must begin by debunking their own biases. And in that spirit I want to put this in a slightly different light by suggesting that we think of them as explorers, intrepid men and women willing to risk their very souls charting the wilderness of ideas.

Using My Religion

If you’ll forgive a bit of exposition, I’d like to take us back to that time and look at how these subversives rose to prominence. Nowadays, when a computer in your pocket can instantly access the bulk of humanity’s accumulated knowledge, it’s easy to underestimate the impact that the first big tastes of science and technology had on culture at the cusp of the 20th century. A wave of discovery had launched science toward its destination as the principle tool for apprehending the world. Every day new technologies dazzled a public that struggled to keep up. Even something as basic to us as electricity was a powerful and deeply mysterious force to the Edwardian laity. Crucially, with the prevailing sentiment of science optimism, no one was giving much thought to the limits of what science might discover. It was not always obvious, even to scientists, what was and what was not science. If radio waves can transmit information invisibly, then why not spirits of the dead roused in a séance?

While there were those who resisted science as a secularizing force, at the same time the potential of undiscovered science shimmered in the collective consciousness as a kind of exotic, unexplored continent of the imaginal. It was in this environment that figures like Kellogg and Crowley thrived, not by rejecting science, but by appropriating it to suit their vision. Kellogg, a Seventh-day Adventist, insisted on the essential “harmony of science and Sacred Scripture.” Crowley boldly claimed that his metaphysical experiments could achieve practical results in the physical world. Magick, he averred, was simply undiscovered science.

Wedded to this new notion of mysticism as a form of occult technology was the theme of embarking on a quest and returning with the gift of knowledge. A common claim was that they had explored the world’s unknown and forbidden places and discovered treasure in the form of wisdom that transcends time and culture. Crowley swore that an ageless angel came to him in Cairo and dictated The Book Of Lies — did Crowley ever interrupt the proceedings for spelling queries, one wonders? Blavastky was said to maintain correspondence with several of the Elder Brothers of the Human Race that she encountered in her travels. These Mahatmas as she called them, function as guardians of a wisdom tradition that predates Christianity.

G.I. Gurdjieff, who, like Peterson regarded biblical texts as woefully misunderstood, claimed to have dedicated his early years to the task of exploring exotic cultures ostensibly as a spiritual quest. His Meetings With Remarkable Men purports to document and syncretise the practical wisdom he had attained. Gurdjieff and Blavatsky may have been tapping into the notion of katabasis, a descent into the underworld, an aspect of the hero’s journey common in myths from many cultures. By claiming to have gone to the far reaches of the world and returned with transcendent wisdom,4 they are making themselves the heroes of their own stories. Jordan Peterson doesn’t have this option. The planet is mapped to the inch, its finitudes now a routine calculus of GPS satellite telemetry, its once-fecund exoticism reduced to picturesque selfie backdrops. But the wilderness of ideas remains a place where souls can be lost.

Peterson’s explorations are of a more bookish sort. He has weathered the furious squalls of Friedrich Nietzsche, penetrated the dense jungles of Carl Jung, and survived the frozen hinterlands of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. But has he returned with the treasure? The answer to that will depend to a large degree on whether you see Peterson as driven by politics or by his work as a clinical psychologist. Not that it’s a simple matter to know. In his YouTube bible lectures, Peterson reconceptualizes the Genesis stories as a kind of primordial self-help book. Abraham’s story of sacrifice becomes a lesson in delayed gratification. The flood becomes a metaphor for surviving the tragedies and trials of life. Transcendent wisdom? Passable. But then something overtly political like class resentment will get smuggled into the Cain and Abel story. No kidding, and it’s this kind of mid-flight engine stall that can have a would-be ticket holder like me wondering if my seat cushion really doubles as a flotation device.5

If you have a more cynical nature, you might be inclined at this point to suspect that Peterson has dusted off one of Crowley’s most reliable parlor tricks. Functioning like a cognitive optical illusion, the trick takes advantage of the brain’s tendency to optimize efficiency by constructing models of increasing abstraction.6 So when ancient tales like Cain and Abel can seem to provide relevant moral lessons in the contemporary world, that new layer of abstraction can feel like truth.7 Sometimes I think an epiphany is simply the brain expressing relief that it has one less rogue data set to account for, one less open file without a drawer to shove it in. It feels good. It feels like your room just got that little bit cleaner, to borrow a metaphor. But here’s the thing. On a personal psychological level Peterson’s observation struck me to the core. How much of my own limited emotional energy has been wasted on useless resentments? How many of those resentments might have metastasized into “bitter malevolence”? And how easily might such bitterness become a kind of hell?

Jordan Peterson talks a lot about hell. Not merely as Christian allegory or Platonic blueprint, but as an actual place that ordinary people wander into daily. He does not shy away from life’s miseries the way someone lauded as an inspirational speaker might. On the contrary, he makes a meal of them, dishing them up with the clinical sobriety of a career soldier who has somehow survived a lifetime in the emotional trenches. At times Peterson seems like a man suffering from PTSD as a result of some trauma he experienced out there in the wilderness of ideas. Visions of “overwhelming and collective murder” as Werner Herzog famously phrased it in the midst of his own descent into the underworld,8 seem to roil within, surfacing as grave warnings about the sickness, disease, depression, madness, malevolence, predation, totalitarianism, and fanatical collectivism that lurk outside the walled garden of ordered existence that we humans create for ourselves.

As Peterson might tell it, much of what those “radical leftists” seek to undo are in fact highly evolved mechanisms to shield society from all of the above. Nevertheless, all this riffing on the dire has the concerted effect of framing his lectures as matters of solemn import. Life and death unfold in the mind’s eye as Peterson sweats it out under the heat of the fresnels. There’s more than a whiff of showbiz in the air here, and Peterson’s years of college lecturing have served to hone a commanding stage presence. Still, there’s something deeply irresistible about watching someone in their element. The man has found his voice, or so I can imagine the lead rep on his CAA team saying.9

Almost Infamous

As of this writing Peterson has taken his one-man tragical history tour on the road, and for the cost of admission you might catch him waxing apocalyptic in a city near you. Everyone wants in, including comedian turned political commentator Dave Rubin, who manages to find time between episodes of The Rubin Report to warm up Peterson’s audiences. Even author and podcast host Sam Harris, after a calamitous first interview that remains one of the most unproductive ism-schisms I’ve ever endured, has climbed aboard for a series of live appearances to hash out their differences.

And the people are coming. People of every sort from what I saw,10 though the subject of just who are Jordan Peterson’s fans is nearly as hotly debated as the man himself. The way Peterson’s detractors heap vitriol on them, you might begin to suspect that they are taking the biblical admonition ye shall know them by their fruits a bit too literally. It’s axiomatic, they seem to imply, that Peterson is an intellectual fraud because his audience is composed of undersexed, over-porned basement dwelling incels.11 It’s a given that Peterson is an ur-fascist because alt-righters love him.12 Of course Peterson is an apologist for the patriarchy, those auditoriums are full of admiring young men.

Houman Barekat’s review of 12 Rules for Life describes Peterson’s readers as, “Gormless dimwits… struggling with masculinity issues.” Matt Welch of Reason magazine has Peterson “playing Pied Piper for a lost generation of lefty-baiting edgelords.” There are pages of similar attempts to delegitimize Peterson’s ideas by way of the rhetorical pump fake to his audience. And while I’m appreciative of the artful insult, much of this invective seems to cross a line. Taken in aggregate, I find it malicious and mercenary. After all, back in the 1980s, no one was making blanket denunciations of Robert Bly’s “Iron Johns” rattling off their Jungian archetypes around campfires and hunkering in sweat lodges to purge their masculinity of toxins. Ditto for the Promise Keepers. Where are the countless articles vilifying the men filling those stadiums as post-pubescent misogynists or inveterate racists?

Remember, if someone wanted to make the lower bar but less damning case that Peterson’s message is coming from what has become an established cultural tradition in the wake of second wave feminism, it wouldn’t be hard. Here’s what Christian pastor and radio host Tony Evans said at one Promise Keepers rally some 20 years ago:

The first thing you do is sit down with your wife and say something like this: “Honey, I’ve made a terrible mistake. I’ve given you my role. I gave up leading this family, and I forced you to take my place. Now I must reclaim that role.”13

Sounds more than a little Petersonish to me. But apparently it’s not damaging enough to write Peterson off as nothing more than the latest prophet of the Mythopoetic Men’s Movement. No, he must be seen as a roving radioactive dump of bad ideas, a “cargo cult intellectual,”14 a dangerous “social order warrior.”15 There are a few theories to account for this scorn. Perhaps the shadow of Trump’s presidency has primed certain writers to see Peterson as a harbinger of some counterculture crypto fascist undercurrent16 — is it wrong to feel nostalgia for the days when it was Commies we were supposed to find under every rock? Or maybe it’s an example of the new tactic in public discourse whereby ideological enemies are dispatched as morally flawed rather than merely wrong. Why bother plowing through your opponent’s “alternative facts” when shaming them out of your hair is just a twitter link to a hit-piece away? Or perhaps we’ve all become so accustomed to our algorithmically enabled cyber bubbles that the slightest pinprick of a successful counter-argument releases hot air in the form of ideological panic.

Now all of this is sounding pretty critical so far, but I’m still not sure if I’ve pre-apologized enough to this point that you might trust me to say something positive about Peterson. I hesitate because it’s something big. One theory that you rarely encounter, but that might better explain all the Peterson censure is the possibility that Peterson has actually tapped into something worthwhile or important. Oh what the hell, I’m just going to blurt it out and see how it sounds: I have a nagging suspicion that Peterson may have put his reproving finger on this generation’s crisis of meaning.

There, I said it. Still with me?

Good. Let me elaborate. First of all, I don’t view crises of meaning as rare. Pretty much every generation has them, sometimes in multiples. They are a natural part of an ongoing dialectic of meaning if you want, and not necessarily tied to younger people, even if the young are often the primary animating force behind them.

There was a famous crisis of meaning in the 60s when all those kids staring at the hamster wheel of generational bourgeois striving hopped a Greyhound for Haight-Ashbury instead. Surely Gordon Gekko’s “greed is good” mantra was an answer to another generation’s crisis of meaning. First amass your fortune, then at least you’ll have the spare time to figure the rest out, right? But what does a crisis of meaning look like to a generation that seems to regard its online presence as both more valuable, and possibly even more real than their corporeal existence? I submit that the current crisis of meaning may be meaning itself.

Enter Jordan Peterson to force a signal moment. In a time when fake news has truth on the run, big data has us doubting our uniqueness, artificial intelligence is robbing us of our most distinctive attributes, and gene editing is poised to flip the script on meritocracy, how is one to, as Peterson might phrase it, construct enough meaning and purpose to make life’s tragedies worth it? Whatever you want to say about him, he has changed the conversation. Those who insist on reducing him to the role of political gadfly may be doing so as means to avoid the larger questions he is posing. Whether or not that’s deliberate, his detractors mostly fail to recognize how he has raised the stakes of the game.

Seeing Peterson’s lecture/show did nothing to dissuade me that he is ready, if not eager to assume the mantle of a generational voice. He morphs effortlessly between charismatic firebrand and humble clinician on a mission. He wants to do for personal responsibility what Timothy Leary did for personal freedom. His answer to “Turn on, tune in, drop out”17 is Nietzsche’s dictum, “He who has a why to live can bear almost any how.” The audience roars when they hear this. Anthem rock for air-philosophers. Leary’s 30,000 man Human Be-In superseded by Peterson’s Human Do-In, 3,000 people at a pop.

Seems everyone wants to breathe the same air as a man with an answer for everything, though I wish Peterson’s answers satisfied me more than they do. His secular sanitizing of Judeo-Christianism,18 his paternalism and individualism, even with all its brilliant psychoanalytical retrofitting, strikes me as too revanchist for prime time. But there again his formidable defense of these begs another big question. Are we going to reconcile with classic liberalism and modernist’s grand narratives, or shut those doors for good? Translating that to Petersonspeak: Are we going to dispense with the transcendent principle and open the landscape to impulsive nihilism?

Jordan Peterson’s rise to prominence, caricatured by his detractors as latter-day tent revivalism for multitudes of burned-over lost boys, might have as much to do with the fact that he is framing his message in a way that forces listeners to confront these larger questions, and that’s a bill that has been buried in our collective in-basket for a long, long time.

Of Iron Johns and Ironists

If you want to wrestle with the problem of constructing meaning in the contemporary world you’re going to first have to go to the mat with irony. Baked into the culture as a default position, irony brands earnestness as the mark of the rube or the fanatic. The catch-22 is that meaning demands that you take a stand for something, earnestness in other words. No problem, as long as the meaning you construct for yourself lies within the accepted bounds of a fairly rudimentary set of established social norms, and as long as those norms provide sufficient meaning to make the tragedy of life worth it. But if they don’t, and you find yourself looking for meaning outside those norms, i.e., taking a stand where everyone else is sitting, you risk exposure and censure. That’s where irony kicks in.

The problem of irony as a meaning-negating force was expressly argued in David Foster Wallace’s 1993 essay E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction. Wallace looked at instances of irony from the 1960s, when writers like Ken Kesey and Thomas Pynchon employed it sparingly as a tool to expose hypocrisy. But by the mid ‘90s, what had begun as postmodern rebellion had morphed into throwaway hipster chic. Wallace regarded irony increasingly as a tyranny of meaninglessness. “All irony,” he writes, “is a variation on a sort of existential poker-face.” And in another passage, irony is “singularly unuseful when it comes to constructing anything to replace the hypocrisies it debunks.”

This dagger to the heart of irony would have no doubt raised the brow of the neopragmatist philosopher Richard Rorty. His 1989 treatise Contingency, Irony and Solidarity divided people into two broad categories, the metaphysicians and the ironists. Metaphysicians believe that the moral dilemmas of ethics, truth, and individual purpose can be solved by wellgrounded theories that converge on general transcendent principles. For them the world is a set of facts that, once revealed and codified, lead to a rationally correct set of values. Metaphysicians believe in an order beyond time and chance that can be described using a “final vocabulary”.

Ironists on the other hand, believe that because languages are made up rather than discovered, no final vocabulary is possible. This means that any description of truth is merely a linguistic property, and any search for truth as such is more akin to a genre of literature than an epistemological inquiry. Intellectual and moral progress is a function of “increasingly useful metaphors” rather than a greater understanding of how things really are. For the ironist, truth, and therefore any meaning predicated on it, is a moving target, a never-ending game of propositional whack-a-mole.

Rorty figured that the number of ironists was growing amongst intellectuals, and he saw this as a positive development. But he cautioned that the ironist stance is largely a private, individual matter. When interacting with greater society you should rely on the local vernacular — what he called the “common sense of the West.” In other words, you should act as if essential truths were attainable. Rorty is no longer with us, but these days irony is on a tear. Banal in its presence, conspicuous in its absence, irony functions like cultural gravity, pulling everything toward the largest mass.

With irony as inescapable as the cell phone, I have to wonder what Rorty would have thought of Lewis Hyde’s admonishment “Irony has only emergency use. Carried over time it is the voice of the trapped who have come to enjoy their cage.” Would Rorty have given the thumbs up to today’s weaponized irony, the kind that Jon Stewart made a career of, the kind that functions like comedic razor wire establishing perimeters of moral cliché in sitcoms, the kind that bullies, shames and silences on social media?

It’s easy to get lost in the weeds of weaponized irony, because self-styled ironistas tend to pop up wherever they are needed to conduct guerilla warfare on behalf of the culture. Thus, Elizabeth Sandifer’s savagely funny takedown, Jordan Peterson — Bumbling Cult Leader or Delightful Satire?19 hails “Jordan Peterson” as a brilliant piece of performance art, a fine example of a style of Soviet-era earnest parody called stiob:

His commitment to the bit is commendable. Peterson is portrayed as a pompous, self-serious buffoon. Though I have to admit, the fake Canadian accent is a bit over-the-top, it really challenges the believability of the character.

Ten years ago it was thought that the march of the ironistas was going to be halted by the countervailing forces of New Sincerity Movement, but today who really believes that this was ever more than a decoy deployed with a clunky wink to reassure the rubes and the fanatics that we have their backs as they step into the lines of fire? The weapon of choice, the social corrective, remains the glancing blow of irony. Sure, we can thank the New Sincerity for giving television and superhero films a new character trope, the smart-ass with the heart of gold, but in the wider context of a culture on a 30-year irony bender, attempts at sincerity tend to feel rote, sentimental, nostalgic and naïve when they work, or emotionally unearned, fake, and cynically manipulative when they don’t. And besides, these islands of sincerity are only embedded into general audience entertainments. Take a gander at the Jordan Peterson reddit fan site Maps of Memeing20 to see weaponized irony stripped of all pretenses to gentility.

The Big As If

Someone had posted an image on the Maps of Memeing site depicting Canadian Mounties marching like Nazi Brownshirts under a giant moose effigy. The caption: “Grand Patriarch Jordan Peterson’s angry young white men on THOT patrol, enforcing monogamy after his coup.” This kind of post, and you see this a lot — irony deployed like close air support for the ground troops of earnestness — raises the question of how these seemingly contradictory forces can coexist without cancelling each other out. Is the person who posted this also following Peterson’s 12 proscriptions, dutifully cleaning his room and stopping to pet cats on the street? Does he/she view this kind of broadside as a personal expression of the mythopoetic hero’s journey? Or is the cultural civil war soldiered exclusively by cyber-ops ironistas whose own search for meaning is sacrificed to the cause of keeping the real world safe for civilian sincerity?

My bet is on the former. Social media has made it easy to step into the fray, deliver the glancing blow, then step back out into civilian life. Part of the appeal of Facebook, Reddit, and Twitter is that these formats allow participants to alternate between performer and spectator. As fields of battle they function like stadiumwave riots, tempting bystanders to pick up a rock and throw it through a window, then fall back into the mob to watch the mayhem circle back around. Everybody else is doing it. The show must go on.

Does this toggling between performer and spectator signal a greater trend in society? Is it possible to shapeshift between ironist and metaphysician without negating both? According to Luke Turner at metamodernism.com the answer to both questions is a cautious yes. His essay, Metamodernism: A Brief Introduction,21 attempts to offer a way out of the modernist/ postmodernist standoff that has defined the culture in recent years.He writes:

Thus, rather than simply signaling a return to naïve modernist ideological positions, metamodernism considers that our era is characterized by an oscillation between aspects of both modernism and postmodernism. We see this manifest as a kind of informed naivety, a pragmatic idealism, a moderate fanaticism, oscillating between sincerity and irony, deconstruction and construction, apathy and affect, attempting to attain some sort of transcendent position, as if such a thing were within our grasp. The metamodern generation understands that we can be both ironic and sincere in the same moment; that one does not necessarily diminish the other. (Italics in original)

Now, unless you are convinced that Wes Anderson is the future of cinema you probably think metamodernism isn’t really a thing. I’d describe it more as aspiring to thingness. But its have-your-cake-and-eat-it appeal is obvious. The as if formulation allows us to make tentative excursions into earnestness while dodging the whack-a-mole hammers of irony. It occurs to me now that Peterson’s “low resolution grand narratives” may be an accommodation to this new way of thinking.

As someone who believes that all meaning, or at least all the good A-list meaning, is socially constructed, I’m willing to be convinced that acting as if your life has meaning has a Darwinian fitness upside. But it’s not entirely clear that such a belief doesn’t out me as a plain old ironist, rather than a hip new metamodernist.

And metamodernism doesn’t take into account the fact that for many, the search for meaning is really a quest for something bigger than themselves. True purpose, almost by definition, is that thing for which you willingly fall on your sword. If your transcendent truth doesn’t mark you as a fanatic, it’s only because the bulk of society shares your enthusiasm. In this light it’s hard not to see metamodernism as anything more than the latest expression of irony’s existential poker face.

Richard Feynman No Longer Takes Requests

So where does all of this leave the would-be earnest young men and women who have yet to come out of the closet as yearners for transcendent truth and meaning in their lives? As I’ve been writing this, one of Christopher Hitchens’ most quoted remarks keeps popping up in my mind. Responding to a challenge to his atheism based on the idea that whatever you hold sacred is essentially your idea of God, The Hitch retorted, “No, nothing is sacred. And even if there were to be something called sacred, we mere primates wouldn’t be able to decide which book or which idol or which city was the truly holy one.”22

It strikes me now as a fine anthem for militating ironists. But then Hitchens, like the other new atheists, was part of what I might call the meaning elite. They enjoy wonderful careers, satisfying intellectual pursuits, positive emotional engagement with the world. They are not schlubs who have seen their best years slip away in a factory, or whose greatest potential lies in the desperate hope that their children don’t fall into the same traps as they.

At Jordan Peterson’s best he is talking past the Hitchens of the world, past the rancor and white noise of gotcha’ journalism in order to deliver a message to those searching for the antidote to despair. That message seems to boil down to gather up enough meaning in your life to make enduring the tragedies that are coming your way worth it. Looking at the world through his lens, it’s easy to understand that a great many people see a loss of faith not as a rational awakening, but a breach in the walled garden that separates habitable order from unmanageable chaos. New atheists have failed to fully contend with the fact that when they ask people to open their eyes to what the non-believer sees as the obvious falsehoods of religion, what those people actually hear is someone asking them to embrace a world without meaning.

For many atheists, truth is the greatest meaning, and an end unto itself. But if they wish to free more people from religious capture23 they need to recognize that their simple truth is no match for the fixed stars of meaning and sheer narrative oomph that religion retails.

Of course, if Peterson were always at his best, I probably wouldn’t be writing this. I want to like him, but he doesn’t make it easy. It’s hard to tell if he is cynically provocative, or passionately principled. Is he a social order Cassandra, or just a sincere worrywart with a big vocabulary? Is he an apologist for the patriarchy, or as Eric Weinstein put it, “a one man answer to the world’s uncle shortage?” Should I be impressed with his willingness to be challenged publicly, or wary about the fact that it’s childsplay for the professional ironistas to turn him into a cutting-room demagogue? I’m suspicious of his bento box approach to self-help, but I’ve heard the saved-my-life testimonials. I struggle to believe that a man as careful as Peterson has failed to see that his tendentious reading of political correctness as the first step in the march to the gulags is precisely the same kind of where-there’s- smoke-there’s-fire alarmism that his opponents engage in when calling him a (choose one: paleo-, proto-, stealth-) Nazi.

Back in the green room in the Thousand Oaks theater I ask Peterson about Captain Ahab. Surely his life was so rich with meaning and purpose that he experienced deep personal fulfillment, so what if he got a few whalers killed? This led to a discussion, well, nano-lecture, about ideology as a meaning disorder to which those with “pathologized neurological machinery” are more susceptible. If I were a real journalist instead of a screenwriter posing as one I might have pressed him on this. I might have asked, weren’t a lot of celebrated historical figures playing Ahabs to the white whales of tyranny, intolerance, exploitation, and disease? But instead my mind went somewhere else. I started to wonder, what if Starbuck had managed just a little bit of hipster irony? Could he have saved the Pequod crew from their watery grave? I flashed on old Ahab, surviving, hitting the lecture circuit to extol the virtues of wooden legs. “That which doesn’t kill you,” and so forth. Moby merch on offer in the lobby.

Later on I observe Peterson’s audience. They hang on every word, but when the brickbats come against “safe spaces”, the “radical left”, the coddling of boys or dangers of weak men, the arms fly up, the cheers ring out. It is evident that what is energizing the crowd is political animus. Peterson may have more to offer those willing to push past the gridlocked space where the culture war rages hottest, but how many are? Crowds are all kink and quirk. Sure, we like our fights, but not like we like our novelty.

A thought experiment: Take Richard Feynman. He was a theoretical physicist, and he was good at it. He worked on the Manhattan project in Los Alamos. He received the Nobel Prize for his collaboration on quantum electrodynamics. In his later years he became a remarkable science communicator and teacher.

He also played the bongos.

Now picture a scene: Feynman taking his show on the road, a mission to bring physics to masses, or whatever. But wherever he goes the audience gives him blank stares — until he breaks out the bongos and lays down a cover of Wipe Out in double time. Suddenly everyone is happily clapping along, finally getting what they came for. The media gleefully covers the tour, but it’s all b-roll of Feynman furiously pounding the skins while reporters warn in grave tones about the moral turpitude of Feynman’s army of beat-worshipping alt-science fans. His manager is like, “Hey, The Feyn Man is just puttin’ his message out there, baby. Didn’t you see how many hits our latest YouTube video got?”

A final anecdote here, it’s not exactly a vessel of transcendent wisdom, but it serves as an appropriate note to go out on. Back in my college days, my roommate Nick was an assistant to a famous artist, who for reasons that will become obvious, I won’t name. Now this was a thankless job in which he did everything from taking out the garbage to playing session guitar (uncredited, bien sur) on the famous artist’s vanity record. So one day, to his surprise, he gets an invitation to dinner and he is stunned to find himself sitting down with the likes of Dennis Hopper and art scene tastemaker Leo Castelli as I recall. Nick tries to settle in and enjoy the dinner, but he can’t stop wondering why the famous artist invited him to meet all his famous and powerful pals. Is this really the generous gesture it appears to be? Does it mean that the famous artist sees Nick as having real potential after all? Could it be that he’s finally accepted Nick as part of his inner circle? And then, somewhere between crêpes à l’orange and the demitasse the Pitiless Universe made its presence manifest. “Nick,” the famous artist said, “why don’t you do your Jack Nicholson for us?”

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 23.3 (2018).

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Well, you can imagine the horror and embarrassment. Some of the people presently staring at him had partied with Nicholson, they knew his kids fer chrissakes. How could he measure up? But Nick wasn’t concerned about all that. Because his Nicholson was world class. If anything Nick’s Nicholson was better than Nicholson’s Nicholson. The famous artist’s crude ambush was actually Nick’s big chance in disguise. It was as if the curtains opened up on a cyclorama sky and the stage manager cued the god rays. He was going to have those Manhattan luminaries falling off their designer chairs. He was going to parlay his moment into a dozen other dinners and win over dozens of other celebs. He was going to become one of them at last. Instead, and to his everlasting amazement, he stood up and said, “I’m not your trained seal,” and stomped the four miles back to the apartment in the driving rain. Nick was the hero of his story that night. He found himself deep in the wilderness of entitlement, belonging, and envy and somehow found his way out, pride intact.

It’s not altogether certain which Jordan Peterson will emerge from the media wilderness he’s been invited into. I have little doubt that he regards himself as the hero of his own story, but how will he juggle the consequences of playing the villain in the stories of so many others? Will he manage to get beyond his role as the mean, mad, white man,24 or will he content himself with a beach ball balanced at the end of his nose?

Not that I would blame him if he did. Applause is applause, is it not? And everything comes down to showbiz these days, does it not? It’s just a matter of finding your audience. One man’s earnest attempt is another man’s ironic entertainment. ![]()

About the Authors

Stephen Beckner is a screenwriter and filmmaker. He is best known for his feature film A.K.A. Birdseye. He is currently developing a feature film project based on the American militia movement of the early 1990s. In addition to his work in film, he has collaborated on video games, notably as head writer for the award-winning multi-platform adventure game Perils of Man.

References

- https://nyti.ms/2BvPibl

- https://bit.ly/2DCcG9H

- See, For example see “How to Think”: https://bit.ly/1kfI5Ai

- By the mid 19th century this was standard practice. L. Ron Hubbard kept the tradition alive, gloriously bloviating “I’ve slept with bandits in Mongolia, and I’ve hunted with Pygmies in the Philippines. As a matter of fact I’ve studied 21 different primitive races, including the white race.”

- Nowhere is Peterson more slippery than in his readiness to port the personal/psychological over to the social/ideological. For example, in any sufficiently complex economic system, there will be many who experience the winning of the few as oppression. Dismissing their experience as resentment, even if this were good medicine in a psychological sense, has little remedial value on the level of the social, but it’s mana to those attempting to morally justify their own position within the economic hierarchy.

- This may remind some of a process known in cognitive psychology as chunking.

- What the Barnum effect is to the individual, the Crowley effect is to ancient myth.

- In his 1982 film Burden of Dreams.

- Creative Artists Agency, one of the top talent agencies in the world.

- To be fair, the prohibitive cost of admission could skew the audience away from Peterson’s younger, less polite fan base.

- A portmanteau of “involuntary celibate,” mostly white, males, heterosexuals who have been unable to establish a relationship or find a sexual partner, though they desire one.

- Here, if you’ve the stomach for it, is a critique of Peterson from an alt-right perspective. Puts to bed any notion that he is their man: https://youtu.be/zR5oJW0MoYw

- Quoted in:Williams, Rhys H. 2001 Promise Keepers and the New Masculinity. Lexington Books, 21.

- https://bit.ly/2NzCkk4

- https://bit.ly/2IIqhSN

- Grab a coffee and read Pankaj Mishra’s “Jordan Peterson& Fascist Mysticism” in the New York Review of Books. You’ll be rewarded with one of the most artful reductio ad Hitlerums you are likely to encounter. https://bit.ly/2lXXXhn

- Marshal McLuhan gave the phrase to Leary. Beware of Canadians bearing gifts.

- Clinical psychologist Alan Fridlund has pointed out that Peterson’s notion of discovering your purpose by assuming personal responsibility is strikingly similar to the Protestant notion of “God has a plan for you.”

- https://bit.ly/2uccz0o

- Reddit: https://bit.ly/2zi4Xiv Facebook: https://bit.ly/2m1WFS

- http://tny.im/fud

- https://bit.ly/2uzpIUr

- I’ll define religious capture as the conviction that the great texts of your religion are specific and literal descriptions of immutable truth rather than a compilation of metaphorical containers for generalized wisdom.

- Michael Dyson’s phrase, from this debate: https://bit.ly/2IYxFJ4

This article was published on October 30, 2018.

“. . . drenched in word salad to sound deeper than they are.”

What a gem!

“If asked if Jesus was a real and the son of God, watch him double-talk, obfuscate, dodge, and contradict himself trying not to say no, like a worm twisting on a hook. ”

This clearly is a sign of certain serious weakness in Peterson’s thought patterns and computations. Why does he not see this?

I mostly do not understand what the hell you are writing about.

I sat through about 12 hours of his classroom via youtube, when he was teaching the Maps of Meaning book referred to in the article. He’s a very captivating speaker to listen to. It reminded me of an interview from KLAX radio done with Charles Manson in prison. They speak in much the same way: very charismatic, and if you accept that their jumping-off point is true they both are very persuasive (for Charlie, that he was innocent and didn’t belong in prison, and for Jordan that everything means what he says it means and could mean nothing else…I accept neither).

I thought he had some very interesting opinions, and a lot of ideas which are worthy of getting behind, particularly his concept of free speech and law. But the content also had plenty of crap; his interpretations of meta-narratives that he presents as is they were facts, drenched in word salad to sound deeper than they are.

I don’t have the standard PC reaction to what he says about gender. I believe he is closer to the truth than the (mostly straw-manned, but not totally invented) people saying biological sex is a “social construct”. But after seeing his discussions with Sam Harris and Matt Dillahunty, I have zero respect for the guy. If asked how many sexes there are, it’s a one-word answer from him (“Two”), anyone saying different is fooling themselves. If asked if Jesus was a real and the son of God, watch him double-talk, obfuscate, dodge, and contradict himself trying not to say no, like a worm twisting on a hook. At that point in the conversation, he goes from being all about truth to a bunch of woo-woo crap. I don’t understand how someone could point out people fooling themselves in case a and then jump through hoops to validate people fooling themselves in case b and be regarded as having any integrity.

As far as his new book full of common-sense advice, good for him. He can be the new Dr. Phil, or at least Canada’s answer to him: An unremarkable clinician giving obvious answers to the rabble, whose only real talent is self-promotion.

This phrase occurred to me: Maundering after plaudits.

maun·der

[ mawn-der]

VERB (USED WITHOUT OBJECT)

1. to talk in a rambling, foolish, or meaningless way.

2. to move, go, or act in an aimless, confused manner: He maundered through life without a single ambition.

plau·dit

[ plaw-dit]

NOUN

1. an enthusiastic expression of approval: His portrayal of Romeo won the plaudits of the critics.

2. a demonstration or round of applause, as for some approved or admired performance.

So many better pieces out there. This author was trying sickeningly desperately to please everyone, but esp. skeptics. I found myself embarrassed reading it (couldn’t finish it all & I’ve read all 3 vols of the Gulag, no problem! :-)

Peterson DEVELOPED his ability to coin a phrase. Read the Intro to Maps of Meaning (at his site) where he tells of his mental hell & the bored voice that started to speak to him over his shoulder (“silently” but audibly in his ear) telling him, whenever he blabbed ideology, “You don’t believe that. ” or “That isn’t true…” Shocked, he stopped talking as much & tried to say ONLY what HE believed to be TRUE, to silence the voice. This started in his teens.

That’s why he has the uncanny ability to express himself with dead-on, fresh, eye-opening and orienting things (vista opening) every other sentence. To get the right words he’ll stop and look heavenward. Not like he’s trying to talk to God or anything, but that’s what he does.

I once hear a “silent voice” but it said over my R shoulder, “WHY do you always SHOW, EXACTLY what you feel? Does he?” I looked over at my husband & he was grinning saying that XY&Z was wrong with me…

I thought, “I was happy before. Why should I lose that now and pout & be in his power for the next half hour till HE works me out of it?” We’d been married 8 years (now it’s been 38!) and this syndrome was familiar.

Due to that voice’s question, I turned to him and said, “What YOU say doesn’t bother me, because I’m HAPPY!” & I gave him the sh*t-ass grin back that he was giving me. He got all flummoxed & said, “But you can’ t DO that! You can’t BE this way!” I faltered but gained strength remembering the Voice (& figuring he wouldn’t hit me), so I said again, “Oh yes I can! Because I’m HAPPY!”

Then we talked and talked and figured out how he’d learned this behavior from his mother. (We thought of many instances.)

If the syndrome popped its ugly head up again, we’d joke. I’d say, “I’m HAPPY!” and he’d say, “I’m happier than you are, because I’m so happy you’re HAPPY!” and we’d laugh & the evil spell was broken.

Isaiah 30:21 (Sorry, Holy Joe has made his appearance) “And thine ears shall hear a word behind thee, saying, This IS the way, walk ye in it, when ye turn to the right hand, and when ye turn to the left…”

Beautifully written piece about a man who stirs up many mixed feelings. However, we need to keep in mind that he is someone who claims to uphold Enlightenment ideals and then goes ahead and cherry-picks climate data to suit a climate change denialist attitude. He is either self-deluded or a out-and-out fraud.

This opinion pieace is well written, but not backed by scientific examination or facts – which is of course nigh impossible when it comes to a discussion of philosophy and psychology in very broad contexts (e.g. the meaning of life…). Unless of course one is prepared to engage in real experiments with religion, communism, marxism, fascism, etc. We all know how that can go so terribly wrong when applied at scale. So we are left with a critical article that amounts to very little content with respect to contested ideas that may or may not be worthwhile contemplating. But one cannot escape the the thought – Jordan Petersen is easily recognised by many, but who is this Stephen Beckner?

That’s a whole lot of words to say “what’s the deal with this Koch Bros funded intellectual who denies climate change, shills for the rich and says lots of sexist, silly stuff”.

A fairly long article that can be summed up as: “I’m envious of how this Peterson guy got so famous. Why not me?”…Just exercising my right to irony.

I think Peterson’s audience is rebelling against the rampant nihilism that exists in our universities. Nihilism may be the truth, but folks don’t like it so they seek something else and thus find Peterson’s message comforting.

Beautiful, engaging writing by Beckner!

Peterson seems to me to be doing for young(er) white men (and some white women) what Oprah has done for black women (and many white women and gay black & white men): promulgating for the present time a neoliberal, cryptoChristianist, individualism-based worldview that remains suspicious of collective approaches/answers to solve wisespread societal problems.

Just as Oprah stepped out of her apolitical world to endorse a neoliberal Democrat (who happened to share her race and inspiring tone), I await the day when Peterson does the same with a popular carbon copy of himself!

Like Oprah, he has a good life now with enough money to further separate himself from his adherents and their daily struggles, which I guess could be the greatest example of irony!

Peterson to me (as a student of theology & culture & identity) and his bestselling text are analogous to what I’ve examined in the megachurch phenomenon. The text/12 Rules against Chaos/ Bible/what have you is the focal point of the communal gathering/sharing by the believers. But just under the surface, and bubbling up between the auditorium talks/Sunday services, is the sociopolitical, the culture warring, the staking of positions & standing their ground of ideology that has harmed and has the potential to erase progress on many fronts so dear to skeptics & freethinkers.

We skeptics feel immediate outrage when the ugly underbelly of the Christian Right uses its scripture, money, & power over human minds to advance an anti-science, anti-civil rights, anti-progress society. But we must not allow ourselves as skeptics to be triggered over “freedom of speech” by the likes of avuncular Peterson. If other educates cisgender white male thinkers like Shermer, Harris, and Haidt throw their political lot with Peterson, will they then be associated with the agenda & sophistry of the likes of Shapiro and Cernovich and Yiannopoulos? Caution advised. Skeptics, apply that skepticism!

Intriguing article, enviably lively writing. But it leaves me grateful to know I’d never heard of Jordan Peterson before reading it.

This piece seems to be intended to display the breadth of the writer’s knowledge rather than to inform the reader. It is not even remotely scientific.

“After all, back in the 1980s, no one was making blanket denunciations of Robert Bly’s “Iron Johns” rattling off their Jungian archetypes around campfires and hunkering in sweat lodges to purge their masculinity of toxins. Ditto for the Promise Keepers. Where are the countless articles vilifying the men filling those stadiums as post-pubescent misogynists or inveterate racists?”

Au Contraire. In the 1980s, leftists and especially feminists were strident in their denunciations of Bly as some sort of crazed male chauvinist, patriarchal ogre. At the time, I was actively debunking the “P.C. science” of the day, the feminists’ beloved “ancient matriarchies” and “recovered memories”, both pretty well discredited now but then fiercely defended. And Bly, by talking about male suffering and identity, violated the acceptable norms of the Left and was denounced as fiercely as Peterson is today. I remember seeing a cartoon in some Leftist publication depicting Bly and his followers as wild apes, smashing things up and swinging in trees.

One time in the late 1980s I saw that Bly was going to be giving a poetry reading near me. I decided that I had to attend, to see what kind of monster this was. Of course, the reality was nothing like that. Bly was soft-spoken, professorial, and even for the most part Politically Correct – he made several of the obligatory put-downs of President Reagan that were used at that time to signal virtue. Bly was very much an intellectual of the left, but his challenge to the dominant ‘male chauvinist / female victim’ paradigm went beyond the acceptable.

As for “Promise Keepers,” they too were endlessly criticized as “post-pubescent misogynists or inveterate racists” or something like that. If you don’t remember this invective, it’s probably because your attention was focused somewhere else.