Do me a favor and picture yourself sitting in the stands at a swim meet. The winner touches the wall after swimming 1650 yards. Now, count to 38 seconds to note the time before the second-place competitor hits the plate that stops the clock: “one one-thousand, two one-thousand, three one-thousand, four one-thousand, five one-thousand….”

When (or if) you get to “thirty-eight one-thousand,” consider the fact that this was the margin between the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) Male-to-Female (MTF) transgender swimmer Lia Thomas and her nearest competitor—teammate Anna Kalandadze—in the 1650-yard freestyle on Sunday, December 5 at the 2021 Zippy Invitational (15:59.71 vs. 16:37.44 in minutes, seconds, hundreds of a second). If you got bored counting and stopped at “five one-thousand”, this was the gap between Thomas and the nearest competition in the 200-freestyle race against Columbia in early November.

A senior at Penn, the 22-year old Thomas from Austin, Texas transitioned from male to female and went through the required one-year testosterone suppression treatment required by the NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association), apparently during the 2020—2021 school year when Covid-19 shut down all swimming meets. Here is the rule in the NCAA Transgender Handbook:

A trans female (MTF) student-athlete being treated with testosterone suppression medication for Gender Identity Disorder or gender dysphoria and/or Transsexualism, for the purposes of NCAA competition may continue to compete on a men’s team but may not compete on a women’s team without changing it to a mixed team status until completing one calendar year of testosterone suppression treatment.

Did the testosterone suppression treatment slow Thomas’s performance? According to Swimming World Magazine it did, but with this qualification:

It’s worth noting that Thomas, from her time on the men’s team, was a six-time finalist at the Ivy League Championships, including three runnerup performances at the 2019 meet. Her times were 4:18.72 in the 500 free, 8:55.75 in the 1000 free and 14:54.76 in the 1650 free. Following hormone therapy, her 2021 times are far slower but still fast enough to be championship quality.

Comparing Thomas’s 1650-yard freestyle time as a man of 14:54:76 to her latest time of 15:59.71 as a transgender woman, the testosterone suppression treatment would seem to have had an effect. To be exact, that 65-second difference constitutes a 7.2 percent decline in performance. Even considering confounding variables—such as the lost-year of competition due to Covid and the subsequent differential training regimes, dietary and other factors—it seems reasonable to conclude that the testosterone suppression treatment has had a nontrivial effect on her performance, to say the least (at the elite level of any sport, a 7.2 percent deficit would likely be the difference from finishing on the podium and somewhere in the middle of the field).

However, it isn’t just Thomas’s performances against her male self that we need to compare; she’s now competing against biological women (those “assigned as female at birth” in the current lingo), and it is that comparison that makes this a controversial subject. According to Swimming World Magazine, since she transitioned from male to female, and subsequently transitioned from the men’s division to the women’s division in swim meets, Thomas has been “crushing the school records” and “is even rising in the all-time rankings: her 200 free performance makes her the 17th-fastest performer in history, and she is less than three seconds off Missy Franklin’s American record. In the 500 free, she ranks 21st all time.” According to Penn Athletics, at the 2021 Zippy Invitational “Lia Thomas delivered another record-breaking performance for the Red and Blue at the event. She won the 200 free with a pool, meet and program record time of 1:41.93. She won the race by nearly seven seconds and her time was the fastest in the country.” One one-thousand, two one-thousand, three one-thousand….

That alone would seem to gainsay this conclusion drawn by Eric Vilain, M.D. Ph.D. and Director of the Center for Gender-Based Biology and Chief Medical Genetics Department of Pediatrics, UCLA, quoted in the Transgender Handbook:

Research suggests that androgen deprivation and cross sex hormone treatment in male-to-female transsexuals reduces muscle mass; accordingly, one year of hormone therapy is an appropriate transitional time before a male-to-female student-athlete competes on a women’s team.

Comparing the swim-times between male Thomas and trans Thomas may support the first part of Vilain’s observation on reduced muscle mass, but the comparisons between trans Thomas and his biological female competitors do not support the second part of the statement when a MTF trans competes against other biological women. Since data is thin in these matters, and anecdotes thick, consider Ellie Marquardt, a Princeton University all-American swimmer who in her freshman year set an Ivy League record in the 500-meter freestyle. This past November Lia Thomas crushed Marquardt in the event by over 13 seconds (4:35.06 vs. 4:48.64). One one-thousand, two one-thousand, three one-thousand….

In my opinion, from the scientific studies and the athletic time comparisons available, the data are simply not there to support this conclusion in the NCAA Transgender Handbook:

It is also important to know that any strength and endurance advantages a transgender woman arguably may have as a result of her prior testosterone levels dissipate after about one year of estrogen or testosterone-suppression therapy. According to medical experts on this issue, the assumption that a transgender woman competing on a women’s team would have a competitive advantage outside the range of performance and competitive advantage or disadvantage that already exists among female athletes is not supported by evidence.

On the contrary, it is not at all clear that one-year of cross sex hormone treatment after puberty turns a biological male into a biological female, at least in the athletic competition sense. Why? Because of all the other differences that result from puberty, most notably a more productive cardiovascular system with larger hearts and lungs that deliver more oxygenated blood to muscles, significantly more upper and lower body muscle mass and corresponding strength in propelling arms and legs, the different leverage strengths from having longer and stronger limb bones and spine, and much else. It is possible, as the NCAA report states, that “transgender girls who medically transition at an early age do not go through a male puberty, and therefore their participation in athletics as girls does not raise the same equity concerns that arise when transgender women transition after puberty,” but that they even note this seems to contradict their statement quoted above. Before vs. after puberty makes all the difference in the world!

As well, the NCAA Transgender Handbook is confused about variational differences between men and women, stating:

Transgender women display a great deal of physical variation, just as there is a great deal of natural variation in physical size and ability among non-transgender women and men. Many people may have a stereotype that all transgender women are unusually tall and have large bones and muscles. But that is not true. A male-to-female transgender woman may be small and slight, even if she is not on hormone blockers or taking estrogen. It is important not to overgeneralize. The assumption that all male-bodied people are taller, stronger, and more highly skilled in a sport than all female-bodied people is not accurate.

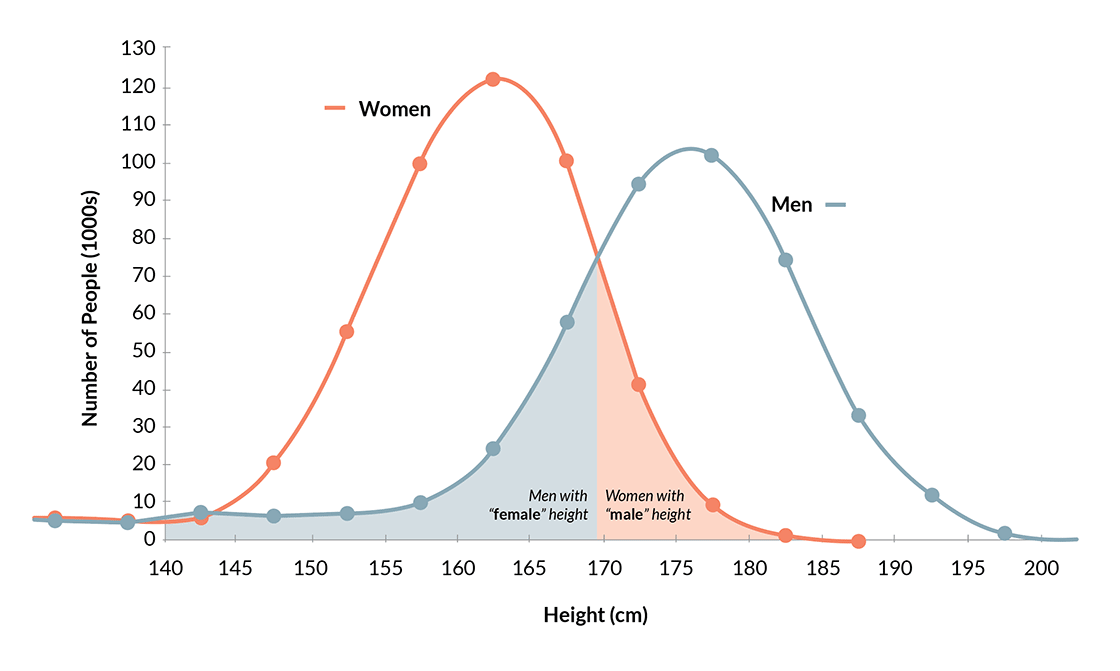

No one who thinks at all about this issue thinks that all transgender women are unusually tall and big-boned muscular men. Picture two overlapping bell curves, like the one (above) for male and female height differences. Of course, there are some men on the far left tail of the men’s distribution who are shorter than most women, and there are some women on the far right tail of the women’s distribution who are taller than most men; but on average men are taller than women, and in such natural variation we can say that most men are taller than most women.

I’ve not found any data graphs like this for transgender athletes, but think of Lia Thomas as a successful male collegiate swimmer falling on the right tail of the men’s bell curve and better than most male swimmers who, after a year of post-pubescent cross sex hormone treatment slides a little ways leftward along the horizontal axis toward the mean for men. But that’s not the comparison that matters! Compared to even elite female swimmers, a slightly (7.2 percent) slower Thomas is still going to be to the right of most women on such an overlapping bell curve comparison, and that makes it unfair for the biologically female competitors.

None of this is to deny that Gender Identity Disorder, or gender dysphoria and/or Transsexualism, are real phenomena, and I mostly agree with the NCAA that “fears that men will pretend to be female to compete on a women’s team are unwarranted.” Of course, it’s possible a few are faking, but from my read of the culture and literature most people who say that they identify as a different gender actually do and are not pretending, especially when gender identity issues arise in early childhood. (I’ll leave aside recent examples of male adult prisoners claiming to identify as female in order to be transferred to female prisons, since they clearly have other motives). Teenagers with no prior history of gender identity issues who suddenly feel trans may be influenced by social media and peer pressure, and much more research is needed to untangle the confounding variables at work to get at the true cause of both gender identity and transgenderism. Suffice it to say, anyone who responds to an analysis like this with “transphobe!” or “anti-trans!” has ipso facto removed themselves from any rational conversation, which is sorely needed at this point in time.

As a lifelong athlete myself (I was a professional cyclist in the 1980s competing primarily in ultra-marathon events like the 3,000-mile nonstop transcontinental Race Across America, or RAAM), I am sympathetic to the role of sports in dealing with personal problems. I can’t count the number of days I’ve been stressed, anxious, or sad for which a long hard bike ride didn’t prove to be salubrious. No doubt this is what Lia Thomas means when she says swimming is “a huge part of my life and who I am. The process of coming out as being trans and continuing to swim was a lot of uncertainty and unknown around an area that’s usually really solid. Realizing I was trans threw that into question. Was I going to keep swimming? What did that look like?” Being able to maintain a daily routine of working out no doubt attenuated much of the stress she went through in transitioning.

And, for the record, I am not against men and women competing in the same division if those two bell curves are sufficiently overlapping. It very much depends on the sport and how the comparisons are made. Returning to the overlapping bell curve diagrams above, by way of example the greatest female ultramarathon cyclist throughout the 1990s was Seana Hogan, who shattered two of my own cycling records. On June 9, 1985, I rode my bike from San Francisco to Los Angeles (city hall to city hall), 401 miles in 21 hours, 47 minutes (18.4 mph). A decade later, on May 11, 1996, Seana Hogan covered the same distances in 19 hours, 11 minutes (20.9 mph), a 156-minute difference, or 12 percent. Seana also broke my Seattle-to-San Diego (city hall to city hall) record of 3 days, 23 hours by covering the same 1,250 miles in 3 days, 16 hours, a 9.3 percent difference. But that’s not the relevant comparison.

In the 1993 RAAM Seana Hogan led the entire race—including all of the men—well into the massive mountains of Colorado. Nevertheless, despite breaking the women’s transcontinental record in a time of 9 days, 15 hours, and 17 minutes, the men’s winner, Gerry Tatrai, covered that same 2,910 miles in 8 days, 3 hours, 11 minutes, a difference of over 36 hours, or 16 percent. In 1994 Hogan broke her own transcontinental record in with a time of 9 days, 8 hours, 54 minutes, and again in 1995 with a time of 9 days, 4 hours, 17 minutes, landing her in 6th place and 4th place overall respectively compared to the men. At some point in the off season when we were discussing whether or not RAAM needed different divisions for men and women (I was Race Director at the time), I asked Seana if we should do away with gender divisions. Her answer was as definitive as it was emphatic: No!

In cycling, as in swimming, the male-female biological differences are simply too substantial to justify doing away with sex/gender divisions, much less having biological men compete against biological women in a women’s division, regardless of what they identify as. The default should be that gender divisions remain in place unless and until there is extraordinary evidence for dissolving them or allowing cross-division competition. (Tellingly, there seems to be no rush of FTM trans athletes eager to compete in men’s divisions, just as there is no run of FTM inmates applying to be transferred from women’s to men’s prisons.)

All that aside, and taking a broader overview, we must not confuse the issues of biological differences with those of rights. Of course we should support trans rights for the same reason we support the rights of people of color, women, and gays: it is immoral (and in many cases illegal) to discriminate against someone based on such immutable characteristics as skin color, gender, and sexual preference, so gender identity should be included in our ever-expanding moral circle and our ever-bending moral arc. The problem arises when there are conflicting rights claims.

I explored this problem in Part 1 of my Substack Skeptic column on abortion, in the discussion on the right of the mother to choose (pro-choice) vs. the right of the fetus to live (pro-life). We have to make a choice about whose rights should prevail, and I made the case that the rights of the adult woman to choose what to do with her body should take precedence over the rights of the fetus, who is only a potential person (biologically and legally) in the first trimester and well into the second trimester (after which abortions are almost nonexistent). But even if you’re pro-life, you still have to make an argument for why the rights of the fetus should prevail over those of the mother.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 27.1

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

In the case of Lia Thomas and other MTF trans athletes, we have a conflicting rights issue between the right of biological women to compete against other biological women who fall within the acceptable bell curve range of female performance vs. the right of MTF transgender athletes to compete against biological women. Given that it seems clear from the current evidence that MTF transgender bell curves of performance do not perfectly overlap with those of biological females, we have to make a hard choice between whose rights should prevail. Given the centuries-long history of women fighting to be treated equally and to enjoy the same rights and privileges as men, including and especially the hard-won Title IX laws that protect women’s sports, it seems clear to me that we should and must continue to support the rights of biological women unless and until scientific research and athletic performance evaluations make it crystal clear that the two bell curves perfectly overlap, and/or until there are enough transgender athletes to comprise their own athletic divisions.

As Thomas Sowell likes to note in his many examinations of myriad social problems, “there are no solutions, there are only tradeoffs.” ![]()

Update

Since this article was first published in Skeptic 27.1 (March 2022), the International Swimming Federation (FINA, Fédération Internationale de Natation) has issued new guidelines for transgender swimmers competing in the sport. Trans women who have experienced any part of puberty will not be eligible to compete in elite women’s swimming on the international stage. We applaud this decision as it preserves women’s sports in particular and rights in general.

About the Author

Dr. Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, the host of the podcast The Michael Shermer Show, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University where he teaches Skepticism 101. For 18 years he was a monthly columnist for Scientific American. He writes a weekly Substack column. He regularly contributes opinion editorials, book reviews, and essays to the Wall Street Journal, the Los Angeles Times, Science, Nature, and other publications. He holds a PhD from Claremont Graduate University in the History of Science. His latest book is: Giving the Devil His Due: Reflections of a Scientific Humanist. Follow him on Twitter @michaelshermer.

This article was published on July 5, 2022.