With the recent brouhaha over the Queen’s funeral crowd size, it might be interesting to explore the ways enormous crowd sizes have been determined in the past, and the science behind crowd estimation.

Way back in 1991, Paul Simon gave a free concert on his Rhythm of the Saints Tour in Central Park. Simon’s promotional poster read, “What If You Threw a Party and 750,000 People Came?” I recall thinking that seemed like an extraordinary number of people. The official tally, I was told later, was somewhere closer to 600,000.

So where did they get that “official” number? How did they count all those people? Short answer—They didn’t! Until recently, extraordinary crowd claims kept growing—and without any supporting data. The 600,000 estimate was used for promotional purposes. In fact, attendance at Simon’s concert was probably much lower than the official estimates, as are official estimates for other concerts.

Those estimates come from the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. According to their website,1 performances such as Simon’s have drawn crowds “estimated at hundreds of thousands.”

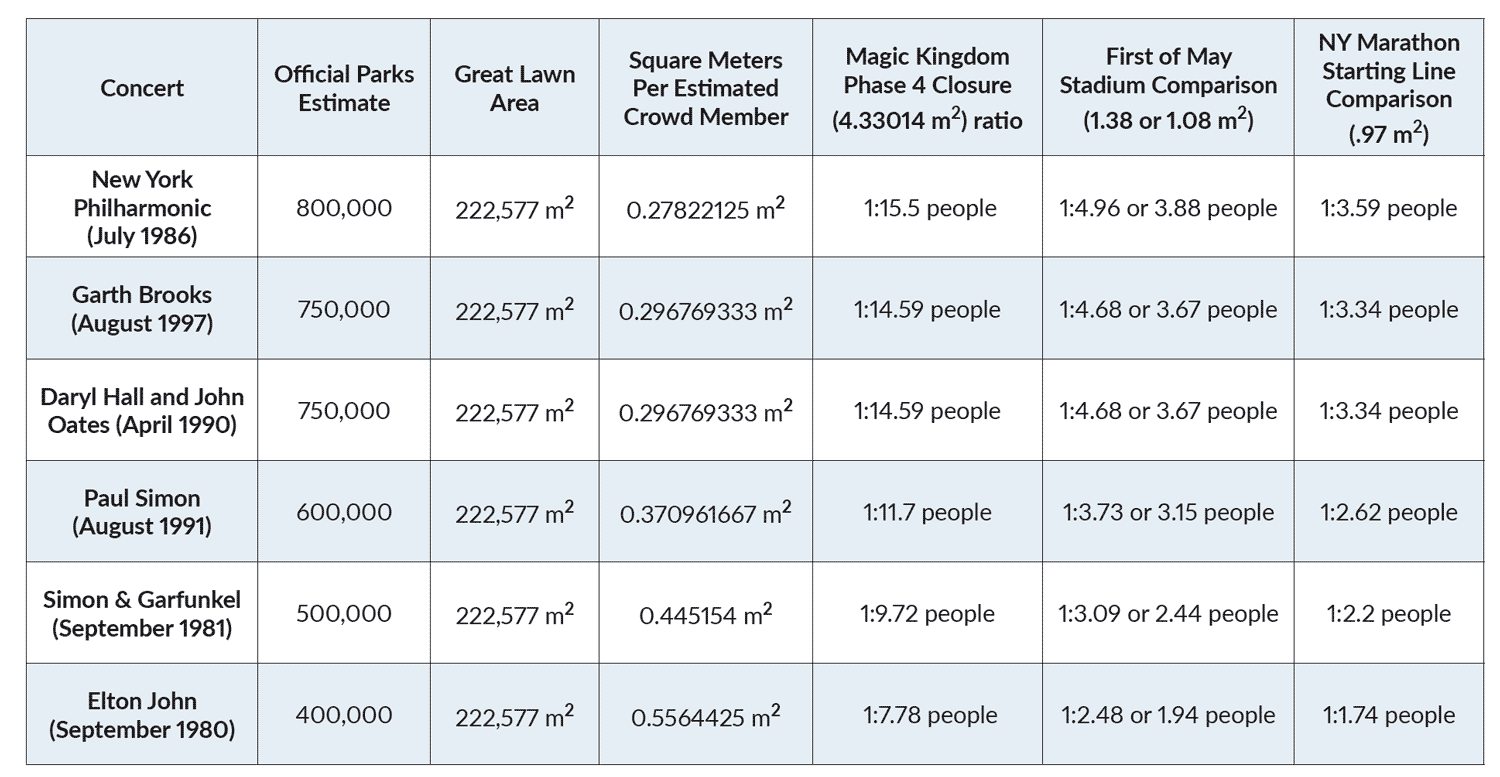

Centralpark.com2 notes “many sources” provided the following estimates:

- New York Philharmonic (July 1986): 800,000 people

- Garth Brooks (August 1997): 750,000 people

- Daryl Hall and John Oates (April 1990): 750,000 people

- Simon & Garfunkel (September 1981): 500,000 people

- Elton John (September 1980): 400,000 people.

In reality, these colossal estimates are provided by publicists for the artists, and they are speculative at best. Meeri Kim of the Philly Voice writes, “…there’s often a hidden agenda behind the number. Event organizers, of course, want to inflate the number of people present, but without the proper equipment and estimation methods, even unbiased parties can be inaccurate.”3

What are the specific equipment and methods on which these estimates are based? The science behind crowd counting began in the late 1960s.4 Herbert Jacobs was a journalism professor at the University of California, Berkeley. Jacobs noticed that the students protesting outside his window were on measured concrete grids. He counted the students on a few grids and derived a rule of thumb for crowd counting: Number = Area × Density. While the science of crowd estimation has developed beyond Jacob’s initial observation (composite images of crowds are now placed into digital 3D models, making heads easier to count), the general formula of Area × Density remains approximately accurate. Crowd counting isn’t an exact science, as crowds move about, but generally: The denser the crowd, the less people move within it.

Mega-concerts take place all over the world in major cities, but one location in particular is famous for them: New York’s Central Park. Unlike Tushino Airfield in Moscow (Metallica, 1991, 1.5 million people estimated) and Copacabana Beach in Rio de Janeiro (Rod Stewart, 1994, 3.5 million people), the space to accommodate spectators is ideal for crowd counting: It is one large, flat oval, with a track surrounding it. The Great Lawn’s surface area is 55 acres, or 222,577 square meters.

Considering those parameters, let us examine three levels of “crowdedness” descending in order, from “very crowded,” to “extremely crowded,” using numbers and space we know to be true.

The square area of Disney World’s Magic Kingdom is 107 acres, which is 433,014 square meters. The park occasionally needs to close due to capacity crowds. It does so in ascending phases according to the number of guests entering the park.5 The final Phase, a “Phase 4 Closure,” excludes all visitors regardless of circumstance. Such a closure is very rare, happening on average only once per decade. On April 7, 2009, the park maxed out at 100,000 people, employees and guests combined. Not counting the space taken by the attractions, food carts, waterways, etc., this means that everybody in the park on April 7, 2009 had less than five square meters to move about (4.33014 m2), slightly less than one third of an American parking space.6

The total floor space of the Rungrado First of May Stadium in Pyongyang North Korea is 207,000 m2 across eight stories. Estimates range between 150,000 and 190,000 spectators and employees, making it easily the largest capacity venue in the world.7 Including the large playing field (limited to athletes and performers), this means each person has between 1.38 square meters (150,000) and 1.08 square meters (190,000), or about one-fourth of the space allotted to guests at Disney World during a Phase 4 Closure. That’s a tight fit, even for undernourished North Koreans (the average North Korean man is 3–8 cm shorter than his South Korean counterpart), but still manageable.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 27.4

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

The starting line of a major city marathon is among the most crowded spaces on the planet. The largest in the world, New York City’s, recorded 51,246 runners in 2017 (minus athletes using wheelchairs, who start earlier) at the starting lines.8 The race was separated into four major waves based on finishing time projections. An aerial photo of the 2017 NY Marathon shows the waves separated by two rows of 14 city buses. The length of an MTA Regional Bus is 12 meters, meaning the length of each wave is about 168 meters.9 The width of each wave is slightly less than two city traffic lanes, each lane encompassing 3.7 meters, a combined width of 7.4 meters.10 This allows an approximate area (168 × 7.4) of 1243.2 m2 per wave. Divided by four, each wave of runners assumes a space of just .9704 m2.

All of the official estimates far exceed that of the (known) New York City Marathon’s starting line. The smallest official concert estimate (400,000) was that of Elton John’s 1980 concert in Central Park. For this estimate to be correct, there would need to be 1.74 concertgoers for every one marathon runner. Consider also that marathoners stand still, shoulder to shoulder, waiting for the race to begin, whereas footage of Elton’s event reveals open spaces and concert attendees dancing.11

In the above table, the Park’s Department estimates are divided into the area of the Great Lawn. I’ve included my comparisons to crowds at capacity at Disney’s Magic Kingdom, First of May Stadium in Pyongyang, and the starting line of the New York City 2017 Marathon: As the technology of crowd counting advances, it seems the days of massive crowd over-estimates have ended. In 2008, Bon Jovi played a free show on The Great Lawn and, in this case, each audience member was counted by workers with clickers at the Lawn’s various entrances. The total? 48,538 people.12 Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe told the New York Times “You look out at the sea of people from the stage, and your mind tells you, ‘That’s what hundreds of thousands of people looks like.’” ![]()

About the Author

John D. Van Dyke is an academic and science educator. His personal website is vandykerevue.org.

References

- https://on.nyc.gov/3TzawNT

- https://bit.ly/3gmrTmV

- https://bit.ly/3TvxTrE

- https://bit.ly/3VHLYUX

- https://bit.ly/3yNDXE3

- https://bit.ly/3TggyTP

- https://bit.ly/3D6OAnZ

- https://bit.ly/3glDxy8

- https://bit.ly/3ePL47Y

- American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials. (2011). Geometric Design of Highways and Streets, p. xli, AASHTO.

- https://bit.ly/3D93p9u

- https://nyti.ms/3CNFAm7

This article was published on January 28, 2023.