We are three college professors who wish to call attention to a growing problem, namely the erosion of the foundational values of a college education: free inquiry and free speech, rationality and empiricism, civil discussion and debate, and openness to new ideas.

The Rise of Critical Theories

Critical theory is a school of thought that has its roots in Marxist theories of human nature and society. It originally developed in Germany in the 1920s among a group of scholars at the Institute for Social Research. They were attempting to salvage some of the failed ideas of Marxism by extending theory to embrace non-economic forms of inequality and oppression.

Critical theorists believe that mainstream knowledge is used to promote the interests of the powerful. Unlike traditional social science, which aims to objectively describe human nature and society by carrying out scientific research, critical theory promotes ideological narratives as self-evidently true. Based on their theories about human nature and social justice, critical theorists promote political activism (or “praxis”), and at times even violent revolution, to achieve their goals.

The predecessor to critical theory, Marxism, simplistically divided people into groups labeled as oppressors or oppressed. Marxism’s original group division was economic—the groups were the oppressive Bourgeois (those who controlled the means of production) and the oppressed Proletariat (the workers). It tried to explain the systemic causes of these group divisions (capitalism) and it developed a set of proposed solutions, including violent revolution, that it presumed would lead to a utopian communist society. These steps, which we will call “Marxist methodology, subsequently became part of critical theories that then focused on additional ways of dividing people into categories of oppressors and oppressed. The Marxist methodology follows the steps shown in Table 1.

- Divide people into two (or more) groups.

- Label one group as the oppressed (“the good”), the other as the oppressors (“the bad”).

- Develop a theory that purports to explain the systemic causes of this division. The theory is often conspiratorial in nature—oppressors are seen as scheming to keep the oppressed in their place.

- Identify and implement solutions. Encourage group solidarity among the oppressed group, promote an “us-versus-them” mentality, groupthink, and adherence to the party line, invent insulting labels to brand members of the out-group, and engage in activism and/or revolution that will purportedly end those social injustices.

Many social movements based on critical theories have used this Marxist methodology, as noted in Table 1.

All these ideological movements have restricted free speech, encouraged an “us” versus “them” political tribalism, employed personal ad hominem attacks against opponents, and promoted cancellation campaigns. While it is important to respect diversity and historical injustices, we should keep in mind that truly liberal worldviews emphasize our common humanity—which is far less divisive.

What Does “Social Justice” Mean?

The new higher education mantra, “social justice” sounds good, but it in fact can refer to either of two often mutually exclusive philosophies: liberal social justice or critical social justice. Though few acknowledge it, increasingly social justice is sold as the former, but practiced as the latter. Consider how they compare in the Table 2.

As is evident, liberal social justice and critical social justice employ two very different methods in determining what constitutes social justice.

Language Revisionism

Critical social justice activists often use the “Motte and Bailey strategy” (see Table 3) to make extreme proposals appear moderate. In this gambit a highly defensible “Motte” position is promoted, while successively working toward a more radical “Bailey” position. This gambit is used often in postmodernist discourses. For example, by asserting that morality is socially constructed, the Motte is that our beliefs are socially influenced, and the Bailey is that there is no such thing as morality or truth. Another example:

- A (non-controversial) Motte position: “We want social justice.” This statement is difficult to argue against, as just about everyone believes in fairness (though they may differ in how they define the term or how to achieve it).

- A (controversial) Bailey position: “We need to re-define social justice as critical social justice and we need to make fundamental (sometimes radical) changes to our society including ending the rule of law, free speech, property rights, and merit systems.” This statement is much more controversial than the Motte, as it suggests that the current social order is inherently unjust and so needs to be overthrown.

Here are more examples of the Motte and Bailey strategies with respect to the re-definition of some commonly used words.

What is social justice when re-interpreted from a critical social justice lens?1

Again, the term “social justice” in common language refers to the liberal social justice conceptions of individual rights and responsibilities, equal opportunity, blind justice, equality before the law, etc., as noted above. These ideas evolved from historic common law, the Enlightenment (particularly the Scottish Enlightenment), and U.S. constitutionalism.

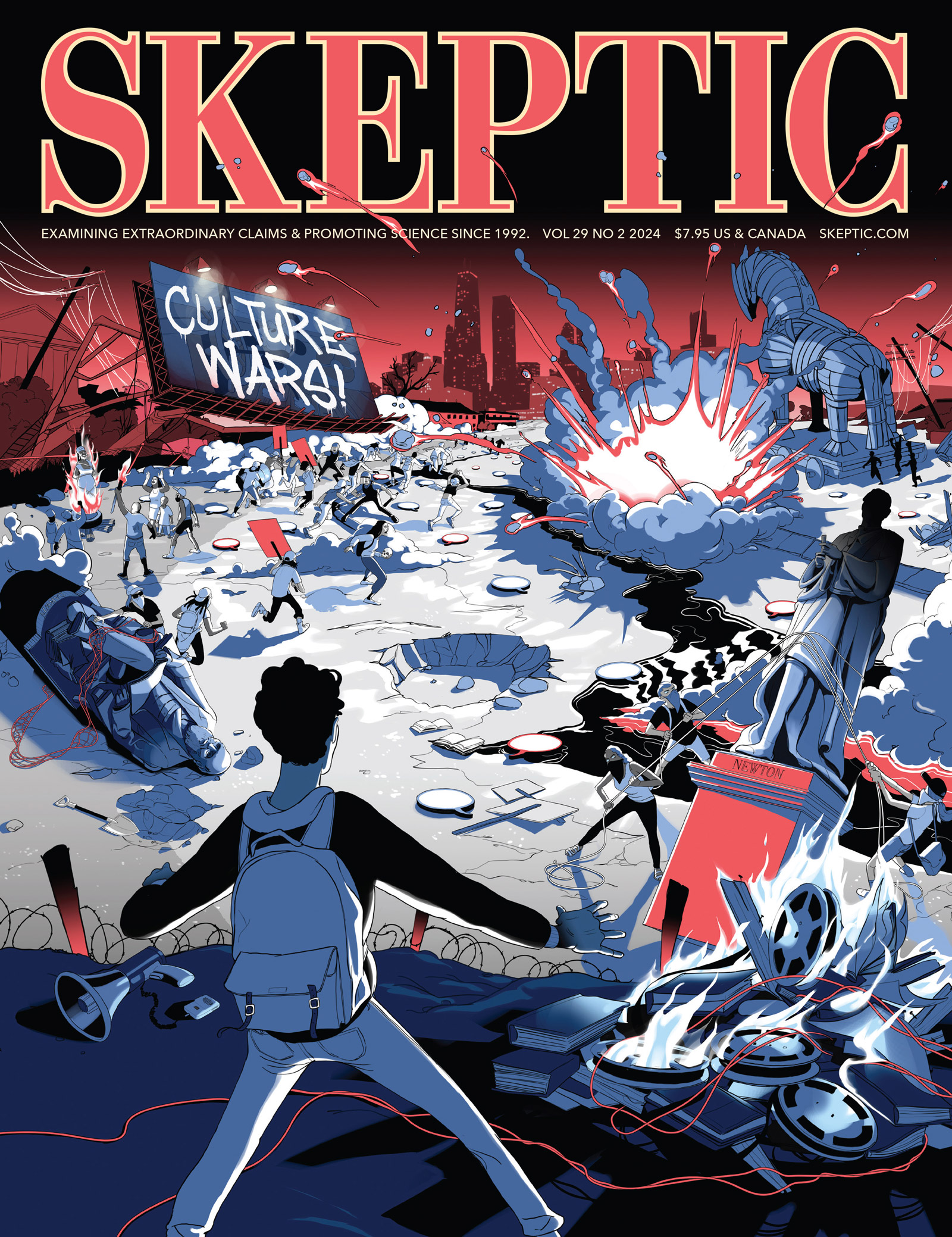

However, over recent decades the term social justice has come to be redefined in terms of critical, not liberal, social justice. This re-definition was accomplished surreptitiously through the Motte and Bailey gambit, and it also allowed the more radical philosophy of critical theory itself to be covertly introduced into college campuses while flying under the academic radar. By analogy, the term “social justice” has been used as a terminological Trojan horse to insert critical social justice and critical theory into the academy under the guise of liberal social justice.

Restrictions on Freedom of Speech and Open Inquiry

This sort of critical social justice activism and indoctrination (as opposed to exposing students to these perspectives in the context of discussing and debating the respective strengths and weaknesses of a range of perspectives) is the opposite of free expression and open inquiry, and thus it is the antithesis of the foundational values of traditional higher education.

Often mere attempts to question how, why, or whether X-injustice is happening leads to accusations that the questioner must be a bigoted “X-ist” or “X-phobe.” Questioning is often dismissed by critical theorists as defensive rhetoric employed to defend one’s privilege and power. The questioner needs thus be silenced, ostracized, and/or canceled. As documented by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), this has in fact happened thousands of times.

Some Examples of Restriction of Speech and Open Inquiry

A series of large-scale empirical studies beginning in the year 2000 found that both students and professors report fearing to express or explore political and ideological viewpoints that are critical of critical theory.2 Further, campuses have little ideological diversity among faculty and administrators, with typically a 12:1 ratio of liberal/progressive to conservative/libertarian, and many departments and some whole fields lacking any conservative or libertarian faculty members. Studies document that many professors freely admit to discriminating against colleagues and students who support liberal, rather than critical, conceptions of social justice. Here are some recent representative examples:

- Bret Weinstein, a former professor of biology at Evergreen State College in Olympia, WA, was deplatformed and forced to resign after he was accused of racism and white privilege for refusing to participate in a “Day of Absence,” which asked white faculty to stay off campus for the day to celebrate people of color.

- Lindsay Shepherd, a teaching assistant at Wilfrid Laurier University in Canada, was suspended after she showed her class a video of a debate about gender pronouns. She was accused of violating the university’s policy on discrimination and harassment.

- Dorian Abbot, an associate professor of geophysics at the University of Chicago, was disinvited from giving a prestigious lecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) after he wrote an opinion piece criticizing diversity initiatives and instead supporting meritbased college admissions, hiring, and promotions.

- Nicholas Christakis, a professor of sociology at Yale University, was placed on administrative leave after he sent an email to students urging them to be civil to those with whom they disagree.

- Ayaan Hirsi Ali, a former Dutch politician and women’s rights activist who herself suffered female genital mutilation as a child in a traditional Islamic society, was disinvited from speaking at the University of California, Berkeley, after students protested her views on Islam.

Critical Pedagogy: Political Activism in the Classroom

Critical pedagogy is an ideological approach to teaching that attempts to impose political views and activism in the classroom that are consistent with critical theory. It was founded by the Brazilian philosopher and educator Paulo Freire, who promoted it through his 1968 book Pedagogy of the Oppressed. It pressures students to adopt a specific political ideology and rejects dissenting views. Doing so takes time away from developing core academic skills, including critical thinking skills.

At its worst, critical pedagogy can produce an environment where some professors and administrators try to tell students not how to think, but what to think. Professors should not be using the lectern as an activist bully pulpit to push their personal ideological or political beliefs. Since professors are in positions of power relative to their students, such activism in the classroom is unethical and constitutes professional misconduct. Students should not be expected to conform to ideologies or dogmas in the classroom.

It is unfortunate that students will very likely be subject to activism on the part of some of their professors and even some fellow students. If they disagree with them, they may at times feel that they should keep their thoughts to themselves. But do not. Speak up!

Spotting Education v. Indoctrination

To be clear, although we do not subscribe to critical theory because of the difficulties with it that we (and many others) have identified, we do not object to a professor teaching or discussing critical theory and critical social justice and presenting his or her opinions about matters based on those perspectives. College is all about exposing students to a range of ideas and opinions. However, professors should not attempt to indoctrinate their students with critical theory or anything else, and they should expose students to a range of perspectives on various issues. Below are a few pointers to help students to identify whether a course or a professor is promoting critical theory through indoctrination rather than education.

Courses that educate tend to have:

- A Balance of Perspectives: Look for courses that present multiple viewpoints and encourage open discussion. A balanced education should expose students to various ideas, even those that challenge the prevailing consensus.

- Freedom of Thought: If a course or professor discourages questioning or presents information as absolute truth without room for debate, it might be indoctrination. In contrast to a fundamentalist religion, education encourages students to question, analyze, and form their own conclusions.

- An Evidence-Based Approach: Knowledge should be grounded in research, evidence, and historical context. If a course lacks substantial evidence to support its claims or relies primarily on emotional appeals, it is less education than indoctrination.

- Engagement with Opposing Views: A healthy educational environment should encourage engaging with opposing viewpoints. If a course dismisses or demonizes dissenting perspectives, it could be leaning towards indoctrination.

Whereas courses that indoctrinate tend to:

Campus activism can be covert rather than overt, with the professor communicating to students what is acceptable or not based on their reactions to student comments, the topics they select to discuss and to omit, their grading practices and feedback, how they interact with and treat students having different opinions, or even their body language when talking about various topics.

A 2007 American Association of University Professors (AAUP) subcommittee report stated such activist professors present their favored worldview “dogmatically, without allowing students to challenge their validity or advance alternative understandings” and such instructors “insist that students accept as truth propositions that are in fact professionally contestable.” Given that professors are in a position of power over their students, this type of behavior is especially inappropriate. And, as far back as 1915, the AAUP advised that professors “should, in dealing with [controversial] subjects, set forth justly, without suppression or innuendo, the divergent opinions” on the issue. This 1915 advisory is still in effect. Indeed, any failure to do so may constitute an ethical breach. Professors should teach students about different sides of an issue and do so fairly, rather than pretending there is just one permitted viewpoint, as in a Marxist or authoritarian organization or system.

What Should Be Done?

First, if students encounter a professor that they believe is using the classroom to engage in ideological or political activism, students should speak up. That may be less risky than students think. Remember, education should empower students to engage in critical thinking and constructive dialogue. If students encounter concerning situations, approach professors for respectful discussions. If needed, seek guidance from department chairs or administrators who value open inquiry. There usually are some.

This article appeared in Skeptic magazine 29.2

Buy print edition

Buy digital edition

Subscribe to print edition

Subscribe to digital edition

Download our app

Often, students cannot rely on their institution’s hierarchy alone—indeed they may be part of the problem. Moreover, there is safety in numbers. Enlist parents and outside organizations to lobby college or university to ensure that it is promoting intellectual diversity, open inquiry, and free thought. (A very simple change is to ask that course evaluations include questions on whether students felt free to voice their opinions in class, whether the professor dealt fairly with students having divergent views, and whether different sides of controversial issues were presented or discussed.)

Today, there are numerous organizations to help students. Currently, the most prominent bipartisan protectors and promoters of free thought are the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) and Speech First. The important thing to remember is that you are not alone. Aside from those organizations, it is certain that many others at their institution will be rooting for students, even if they feel that they can only do so privately.

Second, know that when confronted with transparency (sometimes supplemented with attorneys), bullies tend to back down.

Third, know that the trials students are facing now can make them stronger, and further, are nothing like those faced by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Vaclav Havel, Martin Luther King, Jr., Jackie Robinson, James Meredith, and thousands of others who faced suppression for their beliefs or their identity. The worst fate awaiting students would be having to transfer from a school which does not value free thought to one that does. Students have choices. Make them wisely. ![]()

About the Author

Michael Mills is an evolutionary psychologist at Loyola Marymount University (LMU). He earned his B.A. from UC Santa Cruz and his Ph.D. from UC Santa Barbara. He has served as Chair, and as the Director of the Graduate Program, at the LMU Psychology Department. He serves on the editorial boards of several academic journals and on the executive board of the Society for Open Inquiry in the Behavioral Sciences (SOIBS).

Robert Maranto is the 21st Century Chair in Leadership in the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas, where he studies bureaucratic reform and edits the Journal of School Choice. He has served on the Fayetteville School Board (2015-20) and currently serves on the executive board of the Society for Open Inquiry in the Behavioral Sciences (SOIBS). With others, he has produced about 100 refereed publications and 17 scholarly books so boring his own mother refused to read them, including President Obama and Education Reform (Palgrave/Macmillan, 2012), Educating Believers: Religion and School Choice (Routledge, 2021), and The Free Inquiry Papers (AEI, 2024). He can be reached at [email protected].

Richard E. Redding is the Ronald D. Rotunda Distinguished Professor of Jurisprudence and Associate Dean, and Professor of Psychology and Education at Chapman University. He has written extensively on the importance of viewpoint and sociopolitical diversity in teaching, research, and professional practice. Notable publications include Ideological and Political Bias in Psychology: Nature, Scope, and Solutions (Springer, 2023); Sociopolitical Values at the Deep Culture in Culturally-Competent Psychotherapy (Clinical Psychological Science, 2023); and, Sociopolitical Diversity in Psychology: The Case for Pluralism (American Psychologist, 2001). He is the founding President of the Society for Open Inquiry in the Behavioral Sciences (soibs.com).

Organizations

- The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE). In particular, see its College Free Speech Rankings: https://bit.ly/3T0kbyn

- Campus Reform: campusreform.org

- Heterodox Academy: heterodoxacademy.org

- Academic Freedom Alliance: academicfreedom.org

- Society for Open Inquiry in the Behavioral Sciences (SOIBS): soibs.com

Additional Resources

- Infographic: Critical Theory and Classic Liberalism: https://bit.ly/3uMwOVP

- “Universities must choose between truth or social justice, not both” by Jonathan Haidt https://bit.ly/3Il7ucw

- “The Two Fiduciary Duties of Professors” by Jonathan Haidt https://bit.ly/49FJCwq

References

- This section relies heavily on three works. For the best conceptual analyses of various branches of critical theory, see Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay, Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything About Race, Gender, and Identity. (Pitchstone Publishing). For a sound journalistic account about how critical theory spread across institutions, see Christopher F. Rufo, America’s Cultural Revolution: How the Radical Left Conquered Everything (Broadside Books). Though Rufo has become a political activist, we can attest that his journalistic work is sound, as least as regards those areas with which we are familiar. Finally, the best single work about how critical theory and other moral panics spread, particularly in higher education, remains Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt’s The Coddling of the American Mind (Penguin). Also see Kenny Xu’s School of Woke: How Critical Race Theory Infiltrated American Schools and Why We Must Reclaim Them. (Center Street) and Isaac Gottesman’s The Critical Turn in Education (Routledge)

- Coddling of the American Mind; Eric Kaufmann, https://cspicenter.org/reports/academicfreedom/. Analyzing largescale surveys, political scientist Eric Kaufmann found over a third of conservative professors and doctoral students facing threats of discipline for their views. So have one in ten liberals, often censored by those farther left. Also see Richard E. Redding, “Psychologists’ Politics,” in Craig Frisby, Richard Redding, William O’Donohue, and Scott Lilienfeld, Ideological and Political Bias in Psychology: Nature, Scope, and Solutions (Springer), comprehensively reviewing all historical and current studies on the political views of professors and university administrators.

This article was published on September 6, 2024.