A great plane falls from the sky and takes 230 lives. The newspapers fill with stories of fate’s quirks. Thunderstorms kept another plane on the ground for four hours in Chicago. One of its passengers had a ticket on the doomed plane, which she missed by a few minutes. “Thank God,” she told a reporter. An unfortunate young man arranged to fly a package to Europe as a courier. He planned to visit his sweetheart in London. Joyful at his free ticket and filled with delicious anticipation, he met his death. What does it mean that destiny chose one to survive and the other to die?

Television and the press fill with stories responding to our fascination and horror at life’s uncertainties. What made TWA Flight 800 a target? Why did fate draw these particular people to their common destiny? Literature, great and otherwise, often treats of fate’s powers. The ancients believed that fate worked upon human character to produce inevitable tragedy. Thus honorable Oedipus seeks the truth to save his city and discovers the awful facts of parricide and incest. We moderns are more likely to think that fate strikes us random blows. In The Bridge of San Luis Rey, Thornton Wilder sought the common threads that placed certain people on a collapsing bridge. In Kurt Vonnegut’s novels, fate is a prankster, while John Barth’s novels portray predestined malevolence.

For some centuries the progress of modern science has created the feeling that we, at last, were gaining some control over the unpredictable forces of nature. Ancient scourges, such as smallpox, are gone. The water is safe to drink. We have been secure from war on our soil, and we survive even natural disasters. Even so, many of us believe that our parents and grandparents led safer lives, and we fear that the future will only bring deterioration and danger.

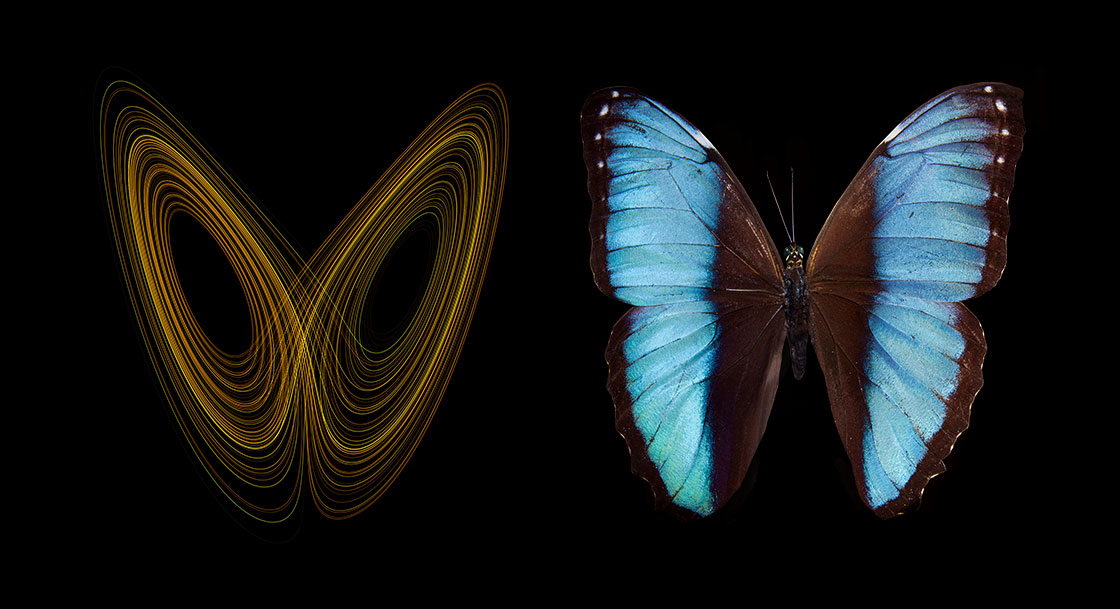

Until recently science, at least, had the reputation for unceasingly improving our ability to anticipate and mold the future. Now scientific discoveries themselves seem to undermine science’s credibility. Chaos theory, sensitive dependence on initial conditions, bizarre strange attractors, and the notorious butterfly effect afflict us. Scientists tell us that the tiniest disturbances in nature lead to wildly unpredictable outcomes. The foundations of physics, the most certain of all the sciences, settle in the liquefied soil of nonlinear systems.

A California butterfly flutters this way instead of that. A tiny parcel of unstable air bubbles skyward. But for the butterfly it would have stayed in its place. Soon a cloud appears. Beneath the cloud the ground cools in the shade while the southwestern sun sizzles the rest. Large swirls of warm air lift soaring birds and draw cooler air from the nearby sea. Each effect is the predictable consequence of its cause, but the result changes the weather sweeping eastward around the globe. As the unpredictable consequence, a great storm douses Rangoon. Are the world’s workings a Newtonian clock or a Rube Goldberg machine?

New Agers triumphantly crow that the human spirit is free and science is dead. They once proclaimed the salvation of free will in the probabilities of quantum mechanics. Now they announce that if physics itself cannot predict the future, then anything may be possible. In a paradox, they believe that the end of scientific predictability offers an answer to the questions of human destiny. The traditional answers, once discredited by the pronouncements of science, now fill hearts with hope. Astrology, faith healing, feats of mind over matter, meditation, and prayer comfort many.

Just as we must know what we are looking at to see it, so we must have the proper language to think about the natural world.

The situation is worse than you have imagined. I here announce an important, if disquieting, discovery. I call it the Butterball Effect. If a small butterfly can cause torrents on the other side of the globe, imagine the disasters that may arise as a turkey desperately flaps to escape the Thanksgiving ax. Is this why winter in the northern hemisphere comes after November’s feasts while the rest of the globe basks in beautiful summer? The evidence is strong that winter always follows Thanksgiving. You object, “But snow sometimes blankets the ground before November 25.” Do not forget that those turkeys meet their ax long before our holiday. Not one of those closed minded establishment scientists has yet investigated this question. Do not fear. It is not too late for us to act. We, and we alone, can save the world from the evils of technology. We must immediately clip the wings of every genetically enhanced, factory-grown turkey.

If the world is so unpredictable, why have scientists discovered this fact so recently? Has the development of chaos theory undermined the premises of science? Does principle or anarchy govern the world? Can we understand the world or will it remain forever unknown? The answers are: They have known for a long time. It has not. It does. We can and it won’t.

Scientists have known for a long time. It is the essence of science to look beyond the frontier, but not too far. All of us, not just scientists, can ask important questions the answers to which are beyond our grasp. Part of the essential talent of a productive scientist is to recognize problems that are solvable. In the middle of the last century, James Clerk Maxwell, the famous physicist, lectured about sensitive dependence on initial conditions and other aspects of modern chaos theory. Beyond identifying these limitations of the physics of his day, he could make no progress. Henri Poincaré, the French mathematician and contemporary of Albert Einstein, pondered and wrote about unstable mechanical systems at the century’s beginning.

Chaos theory does not undermine the premises of science. Chaos theory is a triumph of science. Chaos theory is the extension of principle to what had been only confusion. Chaos theory has taught us the proper language and the principles that govern many previously lawless and unpredictable phenomena. The flapping flag, the dripping faucet, a fibrillating heart all defy detailed predictions, but hidden beneath the apparently random behavior is a strange attractor. These colorfully named mathematical objects label those hidden properties that otherwise differing natural phenomena hold in common.

It is not a failure of natural science when we find that our current theories do not fit every case. As more of nature comes within our understanding, our theories both explain and define their subjects. Newton taught us that, insofar as motion is concerned, we need only consider masses and forces, and he gave us clear definitions of these terms. Quantum theory taught us that it makes no sense to ask what a microscopic object is doing when it is not interacting with the world. Now chaos theory has educated us and added meaningful terms to our vocabulary. We have abandoned the hope, if we ever held it, of predicting the weather on August 1, 2096, until a few days before that date. At the same time our new ideas have taught us the proper time to discharge electricity to reset the functioning of a fluttering heart.

Just as we must know what we are looking at to see it, so we must have the proper language to think about the natural world. Galileo’s notebooks show that the first person to see Saturn’s rings saw handles like a teacup’s, extra moons, earlike extensions, until after several weeks he saw thin flat rings. We have struggled to know what is knowable about randomness. Chaos theory tells us how to think and what to say about unpredictable, fluttery events.

In truth, it is not necessary to eat all the turkeys nor to poison all the butterflies. We must, however, learn to accept the now more understandable randomness of the world. Theodicy is the ancient and unsolved problem of how an infinitely beneficent God can allow evil and random disasters. Thinkers have proposed many answers. In the biblical Book of Job, God makes a wager with Satan. Job loses his wife and family, his health and his wealth. Even a sheltering tree withers. He calls on God for an explanation. Without any evidence of shame, God tells Job to mind his own business. The modern Rabbi Kusher, in his thoughtful book, When Bad Things Happen to Good People, says that God is not omnipotent. He would save us if he could. He does not wish for babies to die of AIDS, but even He has limitations.

My contribution is this. We still find our future mysterious. It is, however, much less mysterious than it has ever been. Scholars tell us that from ancient times until well into the last century, the fraction of people alive in one year who were still alive in the next was small. From birth, the number of survivors plummeted on a path like a child’s slide. Scientists call this curve exponential. They know that total, absolute randomness is the governing law of any phenomenon that produces an exponential curve. This curve describes the decay of radioactive atoms.

Imagine, if you can, what it would mean that death would take, say, one in 10 individuals—a literal decimation— in any one year. It would not matter what their station in life, their efforts to save themselves, their age, sex, or religion. Death by disease, by infection, by injury, in childbirth, by accidents, war, and natural disaster was commonplace. In a world without scientific knowledge filled with such desperate uncertainty, it is no wonder that so many sought the future in auguries, fortune-telling, or astrology.

Today with modern public health and medicine the situation is radically different. If we survive infancy, we are likely to survive to become elderly. During that long period of youth and adulthood, 98 or 99 of a 100 will survive from one year to the next. As before, death chooses its victims randomly. The poor die on the streets from guns and drugs. The rich break their necks falling from their horses. Life still has its imponderables, and the hopes and plans cut short by the TWA disaster are a loss to us all. Still, few of us face untimely death. Let us resolve to face the uncertainties that remain with courage, integrity, compassion, and love. ![]()

About the Author

Dr. Bernard Leikind is a Senior Editor of Skeptic magazine and a plasma physicist familiar to skeptics for his pioneering work in explaining the physics of firewalking, as well as his personal participation in dozens of firewalks. Dr. Leikind has also lectured for skeptics on “strange and unusual atmospheric phenomena,” as well as on the physics of sports, dance, and ballet. He has taught physics and researched at the University of Maryland, UCLA, the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, and General Atomics. He may be the only sensible firewalker, although some consider this an oxymoron.

This article was published on August 31, 2016.

My butterfly fluttered by and reminded me to choose. Goodbye.

“I must believe in free will because I don’t have a choice.”

Nobody said free will can make you logical.

Does a living organism modify its behavior in an unpredictable way based on its local environment? Free will? Just as uncertainty rules in the quantum world, so life, with its unpredictability, modifies the otherwise determined Newtonian universe.

I think that there is a mixture of different things. There is free will (whether be mine, as when I decide to cross the street (or not) or my cat’s (meow for food or catch a mouse) on top of random events (flip of a coin or whatever). So, there is free will but the outcome in the end is complex. How do we know? We don’t. That is what makes reality -and science- so much fun!!!

Human intelligence just gives is information to make decisions but is not the whole thing. It helps, but animal instinct and even plain evolution (as in plants or microorganisms) help as well. What comes on top in the end is anybodies guess.

If we truly had free will, is it possible we’d be unable to make a decision about anything? I recently learned of a woman who due to brain damage isn’t able to make a decision. She wanders the aisles of a supermarket unable to choose between this and that. For her there is no deciding factor. Whereas, I turn over the bottle of salad dressing, see the second ingredient is sugar, put it back. Why? Because I’m hypoglycemic, so I don’t eat sugar, and because I eat it so rarely, when I do, I don’t like the taste. That’s my history, going back to my genetics. I inherited my condition from my father. So I’m able to make a choice. I’m aware of why I’m making this choice, but I wonder about all the choices I’ve made where I’ve had no awareness of how my genes, experience, history have affected them.

You have limited freedom to make a decision, but apparently can’t choose what you think is right, or need to be right, from those limited options. But obviously you’ve been free to ask why.

So if lifes is so random why do you insist weather isn’t?????????

Logic ?

Logic??

We don’t got to show you no steenkin’ logic!!

Weather is a random phenomenon, and the repetitive nature of its randomness is predicable.

Chaos theory is defined as “a small change at one place in a deterministic nonlinear system can result in large differences to a later state.” It could also mean an infinite series of causes and effects traveling along the arrow of time; a kind of chain reaction.

The Butterfly Effect can proceed from the butterfly flapping its wings in Japan that leads to a tornado in Kansas. It follows then, that there is no such thing as an uncaused cause. In other words you can’t get something from nothing.

The Butterfly Effect can proceed from the butterfly flapping its wings in Japan that leads to a tornado in Kansas. But the butterfly was the result of an infinite series of causes, and the events connected to the tornado produce yet more causes and effects over time.

The idea of causation suggests that everything, every event, every action, can be determined. But determinism requires perfect knowledge, including knowledge obtained in real time. Take, for example, the flipping an honest coin and the ability to “determine” with certainty — not probability — whether it will land heads or tails. To do this, you have be able to measure a number of things in real time: The force of the flip, the dimensions (size, weight) of the coin, its trajectory and speed, the distance above sea level, properties of the landing surface, and the direction and speed of any wind, among other things. All of those factors will combine as a series of causes and effects that will ultimately determine whether the coin will land heads up or tails up.

Likewise, this theory of causation prohibits free will. Each of us are the sum of our histories – our genes having come from our ancestors all the way back to the first forms of life. So we come into this world with a lot of history already made an inherent part of our selves; a history over which we had no choice. As we mature from infants to children to adults to old age, our exposure to, and our perception and processing of the external environment, adds to that history, along with any infirmities we may have along the way. We are each unique. Thus, free will is not free, it is irrevocably tied to our history; i.e., to a series of causes and effects. As Sam Harris writes in his book “Free Will,” “You can do what you decide to do, but you cannot decide what you will decide to do.”

So the world is uncertain, especially the future. But that is due in large part by our lack of knowledge. Absent the knowledge of causation, chaos will remain the default explanation.

“a small change at one place in a deterministic nonlinear system can result in large differences to a later state” because they are determined by the unforeseen change and NOT by any form of predetermination. Do you understand the difference between an indeterminate universe and a determinate one. Do you understand that a butterfly moves its wings by choice, and if all such choices had been predetermined in advance, why had that unknown predeterminer determined (and apparently freely) from the start of universal time that “choice making” was needed to appear to determine what was being predetermined as an inevitable choice?

The logic of determination itself clearly shows us that predetermination is illogical, and that even for the illogical to exist, its users needed logic to make any sort of choice at all.

Science has utilizing its methods revealed a Cosmos more consistent than ever before. Having said that there are always going to be mysterious things to investigate. As an undergraduate I never heard of dark energy or dark matter. Why are they called dark? It is just because we have yet determined what they are. However, we now see how dark energy is causing the universe to increase its expansion rate and how dark matter appears to be the key to understanding how galaxies form. I am pretty sure we will be able to figure out what is going on here in the near future. That is what makes scientific investigations so much fun!

Ho Hum

Chaos theory rerun

good way to avoid free will and re hjjhkjgfdwjhbkpokguyjkhhg sponibility

I’m sure that mentioning the the stunning ignorance of the concept of Countable vs. Uncountable infinite sets is politicallically incorrect among chaos snerds.

epecsphedian

NOT a chaotic word

Dr. Sidethink

The author has still not plumbed the depth of the Oedipus paradox. The tragedy occurred as it did because Oedipus’s father knew it had been prophesied, and tried to avert it.

Think of all those excess road accident deaths when Americans, after 9/11, were briefly terrified of flying. To quote Seneca, “Often, when seeking to avoid our fate, we run towards it”. Feedback from expectation introduces yet another level of instability to our predictions, over and above chaos.

I find it somewhat humorous to categorize degrees of chaos; like infinity and whether there is a deity, absolute attributes are at best theories. It makes for interesting reading for amateurs and good work for naturalists and writers.