Part 2 of the documentary film “Lance” airs tonight on ESPN and served as a catalyst for this article that employs game theory to understand why athletes dope even when they don’t want to, as well as thoughts on forgiveness and redemption. The article is a follow up to and extension of Dr. Shermer’s article in the April 2008 issue of Scientific American.

All images within are screenshots from Marina Zenovich’s 3 hour and 22 minute film and are courtesy of ESPN, who provided a press screener. In appreciation. Zenovich also produced Robin Williams: Come Inside My Mind (2018), Water & Power: A California Heist (2017), Richard Pryor: Omit the Logic (2013), and Roman Polanski: Odd Man Out (2012).

Toward the end of Marina Zenovich’s riveting documentary film on Lance Armstrong, titled simply Lance and broadcast on ESPN May 24 and May 31, 2020, the former 7-time Tour de France champion grouses about the apparent ethical hypocrisy of why TdF champions like the German Jan Ullrich (1997), the Italian Marco Pantani (1998), and himself (1999–2005) were utterly disgraced and had their lives ruined because of their doping, whereas cyclists such as the German Eric Zabel, the Italian Ivan Basso, and the American George Hincapie are “idolized, glorified, given jobs, invited to races, put on TV” even though they’re “no different from us” inasmuch as they doped as well. Of Pantani, whom Armstrong famously battled up many a mountainous climb, Lance scowls that “they disgrace Marco Pantani, they destroy him in the press, they kick him out of the sport, and he’s dead. He’s fucking dead!” Ditto Ullrich. “They disgrace, they destroy, and they fucking ruin Jan Ullrich’s life. Why? … That’s why I went. Because that’s fucking bullshit.”

This invective, in fact, comes on the heels of the most touching moment of the nearly 3.5-hour film, in which a lachrymose Armstrong loses his tough-guy composure when asked why he spontaneously flew to Europe to support his former rival in his time of need. Ullrich’s life was unraveling after a series of incidents involving drugs, alcohol, and violence, and Armstrong’s emotional fracture in recalling it is so out of character from his public image that it may give even his most cynical critics pause. His answer? “I love him.”

That a quintessentially straight jock from Texas would admit on camera that he loves another man surely humanizes someone who has otherwise for decades been a picture of leather-neck toughness, a “badass motherfucker” as his former teammate Floyd Landis describes him. If he were a 1950’s test pilot he’d be a steely-eyed missileman staring down the sound barrier. If he were a boxer he’d be Jake LaMotta mercilessly pounding opponents into the canvas. If he were a basketball player he’d be Michael Jordan, entering each sporting contest like it was a matter of life and death, which it was for Lance. “I like to win,” he told filmmaker Alex Gibney, “but more than anything, I can’t stand this idea of losing. Because to me, losing means death.”

That such a film as this is so widely viewed, coming as it is on the heels of the most-watched show in ESPN history, on Michael Jordan’s final season with the Chicago Bulls, is one answer to Lance’s puzzlement about the asymmetrical treatment he has received. It was over two decades ago (1999) that Lance won his first Tour de France and was invited to Bill Clinton’s White House. To put this into further perspective, Armstrong won his 7th and last Tour de France two years before Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone in 2007. That seems a lifetime ago, and yet we’re still talking about Lance Armstrong. Why?

To answer the question I think we must distinguish between Lance’s doping that was, in fact, a logical outcome of a corrupt system that forced most top cyclists at the time to choose between cheating and quitting, from his mendacity and intimidation to enforce Omerta that included threats, lawsuits, libelous public statements, and alleged backroom deals that harmed anyone who threatened to break their silence. As well, to invoke the title of Armstrong’s bestselling memoir, it was never about the bike and always about Lance. As the idiom suggests, those who reach great heights have further to fall. In short, the continued interest in the rise and fall of Lance Armstrong has more to do with the human condition and what it reveals about our species and the wicked games we play.

The Dope on Doping

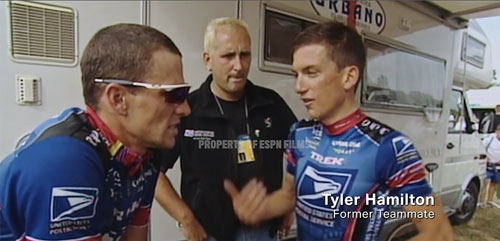

Doping has long been a part of cycling. From the 1940s through the 1980s stimulants and painkillers were ubiquitous. As the 5-time Tour winner Jacques Anquetil snorted, “You can’t ride the Tour de France on mineral water.” And when challenged to elaborate, quipped: “Everyone in cycling dopes himself. Those who claim they don’t are liars.” With that as the norm, doping regulations were virtually nonexistent until the British champion Tom Simpson keeled over dead on the climb up the legendary Mont Ventoux in the 1967 Tour. An autopsy revealed a pharmacopoeia of drugs in his body and a vial of amphetamines in his jersey pocket. But even after that tragedy and the implementation of incipient testing, the dopers were always ahead of the doping controls. When I was competing in the 3,000-mile nonstop transcontinental bicycle Race Across America in the 1980s blood doping was both popular and allowed until after the 1984 Olympics and was a quantum leap over earlier techniques, but I begged off it because it seemed medically risky to inject a bag of your own or someone else’s blood in order to boost the amount of oxygen-carrying red blood cells in your system. Lance’s teammate Tyler Hamilton, in his 2012 book The Secret Race, recounts horror stories about injecting bags of spoiled blood and the illness that followed.

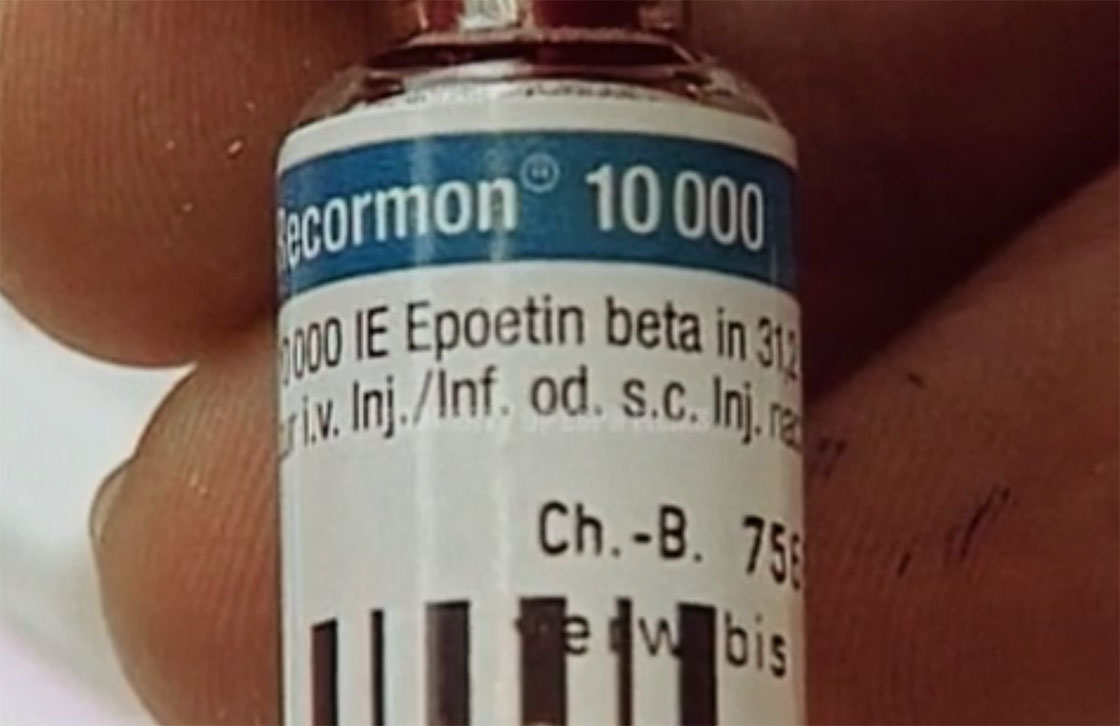

This risk was averted in the early 1990s, before Lance entered the sport professionally, with the introduction of genetically engineered recombinant erythropoietin — r-EPO. Natural EPO is a hormone released by the kidneys into the bloodstream, which carries it to receptors in bone marrow, stimulating it to pump out more red blood cells. Chronic kidney disease and chemotherapy can cause anemia, and so the development of the EPO substitute r-EPO in the late 1980s was a savior for chronically anemic patients … and oxygen hungry endurance athletes. Taking r-EPO is just as effective as getting a blood transfusion, but instead of messing around with bags of blood hanging from hotel room picture hooks and poking long needles into uncooperative veins, cyclists could now store tiny ampoules of r-EPO on ice in a thermos bottle or hotel minifridge, then simply inject the hormone under the skin, boosting the rider’s hematocrit (HCT), or the percentage of red blood cells in the total volume of blood. The normal range of HCT is in the mid-40s. Endurance training can boost it naturally into the high 40s or low 50s. Multi-week stage races like the Tour de France cause HCT to steadily decrease. EPO can push those levels into the high 50s and even the 60s and keep them there. Bjarne Riis, the winner of the 1996 Tour de France was nicknamed “Mr. 60 Percent”, and in 2007 he confessed that EPO was behind his moniker. After a test was developed in 2000 that could detect EPO, dopers shifted to micro-dosing it intravenously and/or returning to blood doping under tight supervision.

How big a difference does EPO make? In Zenovich’s film Armstrong’s U.S. Postal teammate Jonathan Vaughters makes a back-of-the-envelope calculation that the drug enhances performance by about 10 percent. In a 100-hour race in which the first and last place riders are separated by two hours, or two percent, this is a game changer. The infamous sports physiologist and convicted doping doctor Michele Ferrari, who for years worked exclusively with Armstrong and the U.S. Postal team, quantified the effect for me more specifically when I interviewed him for a 2008 article in Scientific American on doping in sports: “If the volume of [red blood cells] increases by 10 percent, performance improves by approximately 5 percent. This means a gain of about 1.5 seconds per kilometer for a cyclist pedaling at 50 kilometers per hour in a time trial, or about eight seconds per kilometer for a cyclist climbing at 10 kph on a 10 percent ascent.” Thus, a cyclist who boosts his hematocrit by 10 percent can lop off 75 seconds in a 50-kilometer time trial, which is typically decided by a few seconds, or 80 seconds per climb on any of the numerous 10-kilometer 10 percent mountain passes the riders negotiate in the Pyrenees and Alps, often decided by a few tens of seconds. This advantage is not one that athletes can afford to give away to their competitors.

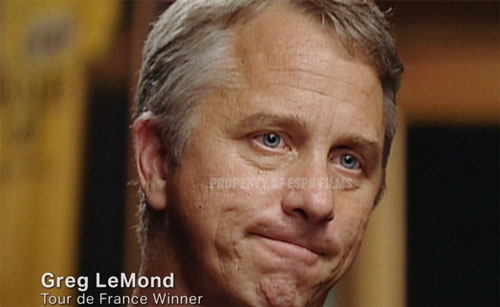

EPO forced cyclists into choosing between doping and quitting the sport, as the three-time Tour winner Greg LeMond discovered in 1991. After logging victories in 1986, 1989 and 1990, LeMond set his sights on equaling or bettering the record of five Tours de France achieved by only three cyclists before him — Jacques Anquetil, Bernard Hinault, and Eddy Merckx. “I was the fittest I had ever been, my split times in spring training rides were the fastest of my career, and I had assembled a great team around me,” LeMond told me. “But something was different in the 1991 Tour. There were riders from previous years who couldn’t stay on my wheel who were now dropping me on even modest climbs.” The following year was worse, as LeMond refused to dope and would not allow his teammates to either. The result: “our team’s performance was abysmal” and “I couldn’t even finish the race.”

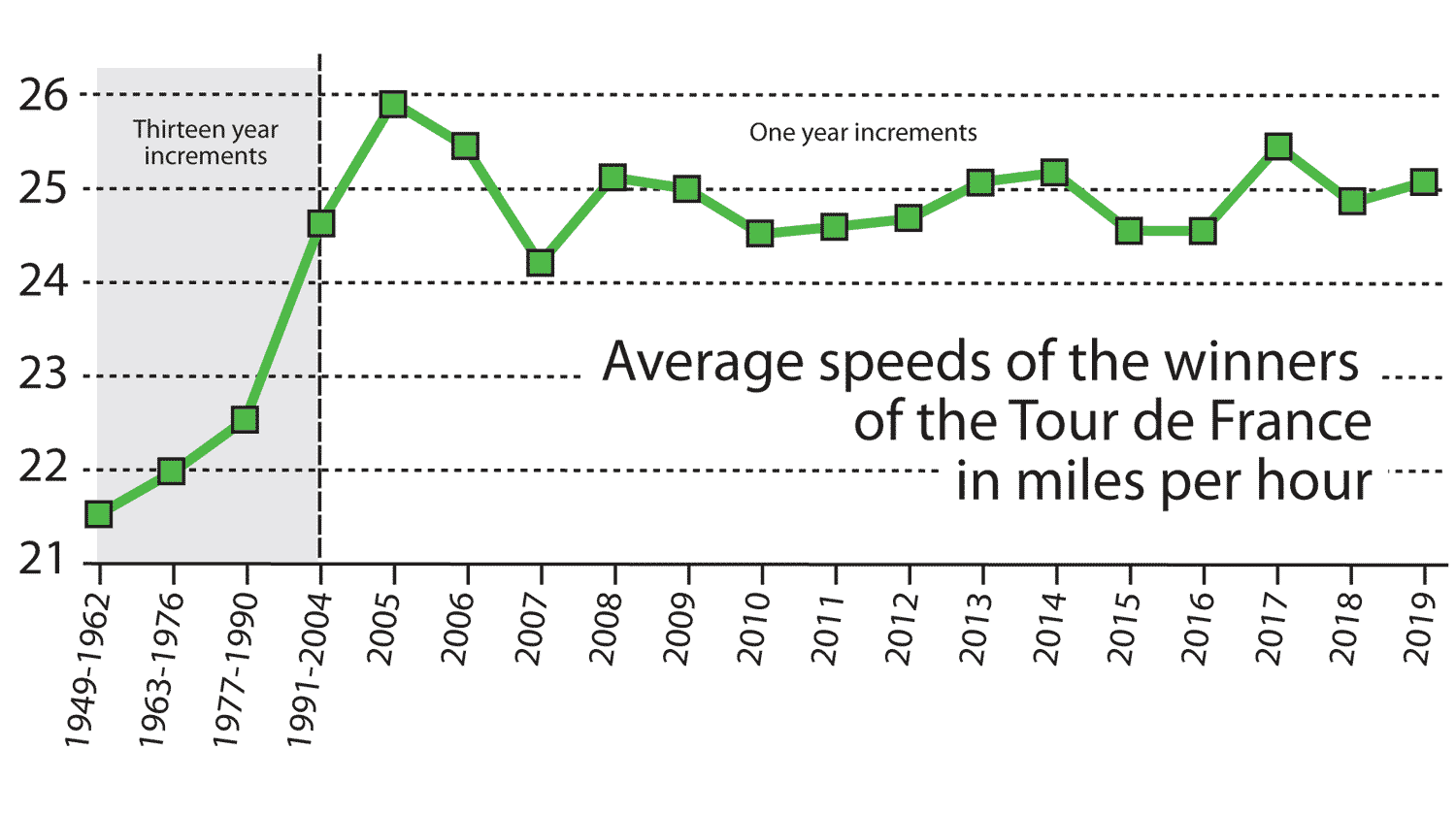

Greg’s hunch is backed by data. Average speeds of the winners of the Tour de France spiked upward beginning in 1991. To control for yearly variance effected by course changes and weather over time, I averaged the speeds over 14-year periods going backward and forward in time from 1991, then compared those to the peak Armstrong era and after. The averages are plotted on the graph below. In the period 1991–2004 the winners’ average speed jumped 9 percent over the corresponding speed in the period 1977–1990, an increase that cannot be accounted for by improvements in equipment, nutrition or training. Lance’s final victory in 2005 is the fastest Tour ever recorded at 25.9 mph. The extensive disqualification of dopers in 2007 brought the average speed down to 24.2 mph. It has hovered around there ever since, bouncing around between 24.5 mph and 25.1 mph through 2019, with an average speed between 2008 and 2019 of 24.9 mph. The spike in 2017 may be a statistical anomaly or the product of varying race conditions, but it is interesting to note that the winner, Chris Froome, later that year tested positive in the Tour of Spain for salbutamol, an asthma medication that opens up the medium and large airways in the lungs. Although Froome was ultimately cleared by the UCI, it is a curious thing that some professional cyclists seem to come down with asthma around the time of the three grand tours.

Join the Club or Go Home and Get a Real Job

In his bestselling book Game of Shadows, the San Francisco Chronicle investigative reporter, Lance Williams, who broke the BALCO doping scandal in baseball, made this observation: “Athletes have a huge incentive to dope. There are tremendous benefits to using the drugs, and there is only a small chance that you will get caught. So depending on your sport and where you are in your career, the risk is often worth it. If you make the team, you’ll be a millionaire; if you don’t, you’ll probably go back to driving a delivery truck.” Armstrong’s teammate for many years, Tyler Hamilton, confirmed to Zenovich that the logic applied to the sport of cycling as well: “It was either join the club or go home, finish school, and get a real job.”

Once it becomes known that the top competitors in a sport are doping, the rule breaking cascades down through the ranks until an entire sport is corrupted. Based on his numerous interviews with athletes, coaches, trainers, drug dealers and drug testers, Williams estimates that between 50 and 80 percent of all professional baseball players and track and field athletes were doping. Given that reality, Williams told me, “There is the conviction that everyone they are competing against is cheating already.” By way of example, Williams noted that Charlie “the Chemist” Francis, coach of Ben Johnson, the sprinter and (briefly) 1988 Olympic gold medalist in the 100-meter run who was busted for doping and stripped of his medals, told him that the doping was “completely self-defensive.” How so? “It was cheat or lose.”

Armstrong’s U.S. Postal teammate Frankie Andreu, a domestique in support of the team leader in the mid 1990s, told me: “For years I had no trouble doing my job to help the team leader. Then, around 1996, the speeds of the races shifted dramatically upward. Something happened, and it wasn’t just training.” Andreu resisted doping as long as he could, but by 1999 he was unable to do his job: “It became apparent to me that enough of the peloton was on the juice that I had to do something.” He began injecting himself with r-EPO two to three times a week. The boost was exactly what he needed “to dig a little deeper, to hang on to the group a little longer, to go maybe 31.5 miles per hour instead of 30 mph.” That seemingly small difference is actually larger than it appears as it can make the difference between staying in the peloton and getting dropped; when you’re dropped and unable to enjoy the drafting benefits of riding in a large pack of riders, that can spell the difference between staying in the race or taking a flight home. This is where the game theory matrix of incentives kicks in.

The Game Theoretic Logic of Doping

Game theory is the study of how players in a game choose strategies that will maximize their return in anticipation of the strategies chosen by the other players. The “games” for which the theory was invented are not just gambling games such as poker or sporting contests in which tactical decisions play a major role; they also include serious life matters in which people make economic choices, military decisions, and even nuclear diplomatic strategies like Mutual Assured Destruction, in which neither nation (the US and USSR during the Cold War) has an incentive to launch a nuclear first strike because the other guy will retaliate in kind, leaving both countries decimated. What these “games” have in common is that each player’s “moves” are analyzed according to the range of options open to the other players.

The game of prisoner’s dilemma is the classic example: You and your partner are arrested for a crime, and the two of you are held incommunicado in separate prison cells. Even if neither of you wants to confess or rat out the other, the D.A. can change your incentive through the following matrix of options (depicted visually in the table):

- If you both remain silent, you each get a year (top left).

- If the other guy confesses and you do not, you get three years and he goes free (top right).

- If you confess but the other guy doesn’t, you go free and he gets three years in jail (bottom left).

- If you both confess, you each get two years (bottom right).

With these possible outcomes the logical choice is to defect from the advance agreement and betray your partner. Why? Consider the choices from the first prisoner’s point of view. The only thing the first prisoner cannot control about the outcome is the second prisoner’s choice. If the second prisoner remains silent then the first prisoner earns the “temptation payoff” (no jail time) by confessing, but gets a year in jail (the “high payoff”) by remaining silent. The better outcome in this case is for the first prisoner is to confess. But if the second prisoner confesses, then once again the first prisoner is better off confessing (the “low payoff” or two years in jail) than remaining silent (the “sucker payoff” or three years in jail). Because the circumstances from the second prisoner’s point of view are entirely symmetrical to the ones described for the first, each prisoner is better off confessing no matter what the other prisoner decides to do.

The prisoner’s dilemma game has been played in many experimental conditions, revealing that when subjects play the game just once or for a fixed number of rounds without being allowed to communicate with the other prisoner, defection by confessing is the common strategy. But when subjects play the game for an unknown number of rounds, the most common strategy is tit-for-tat: each begins cooperating with the prior agreement by remaining silent, then mimics whatever the other player does. Even more mutual cooperation can emerge if the players are allowed to communicate and establish mutual trust. But once defection by confessing builds momentum, it continues throughout the game and cheating becomes the norm.

“It was either join the club or go home, finish school, and get a real job.” —Tyler Hamilton

In cycling, as in baseball and other sports, the contestants compete according to a set of rules, which clearly prohibit the use of performance-enhancing drugs. But because the drugs are so effective and many of them are so difficult to detect, and because the payoffs for success are so great, the incentive to use banned substances is tempting. Once a few elite athletes defect from the rules by doping to gain an advantage, their rule-abiding competitors must defect as well. But because doping is against the rules, a code of silence — Omerta — prevents any open communication about how to flip the matrix incentives and return to abiding by the rules.

Nash Equilibrium and the Level Playing Field

In game theory, if no player has anything to gain by unilaterally changing strategies, the game is said to be in a Nash equilibrium, discovered by the mathematician John Forbes Nash, Jr., (portrayed by Russel Crowe in the film A Beautiful Mind), who went on to win the Nobel Prize in economics for his pioneering research in game theory. When everyone in a system violates the rules, or if everyone just thinks that everyone else is violating the rules (even if they are not all so doing), cheating can become a Nash equilibrium, which turns it from a moral violation to a rational choice. As the title of an article analyzing average Tour speeds put it: “Doping: A Necessity, Not a Sin.” But if everyone outside the system thinks that the rules are enforced (even while those inside the system know better), fans respond accordingly with moralistic punishment for the cheaters.

I have yet to see anyone inside or outside the sport explain it this way, which in a manner of speaking at least partially absolves the athletes while shifting some the moral culpability to the regulatory bodies of the sport. That is, the governing bodies of a sport must change the payoff values of the expected outcomes identified in the game matrix. First, when other players are playing by the rules, the payoff for doing likewise must be greater than the payoff for cheating. Second, and perhaps more important, even when other players are cheating, the payoff for playing fair must be greater than the payoff for cheating. Players must not feel like suckers for following the rules.

In a Nash Equilibrium of mass doping, is it a level playing field? That is, if everyone was doping then can we at least conclude that the best cyclist won all those Tours de France (not just Lance, but Pantani in 1997, Ullrich in 1998, and the others before and since)? We will never know for sure, of course, and while it is unlikely that 100% of cyclists were doping, it is telling that none of Lance’s competitors who were in a position to win but were bested by him are claiming victory or demanding restitution (and every one of the podium finishers in all seven of Lance’s TdF victories was eventually busted for doping and/or later confessed to it). In any case, anyone who would join a Fair Play for Other Dopers Committee would find it difficult to gain much sympathy among ethicists.

Anyone who would join a Fair Play for Other Dopers Committee would find it difficult to gain much sympathy among ethicists.

Some have argued that Lance’s extensive resources that enabled him to hire the best sports physiologist in the world for exclusive preparation gave him an edge over his competitors. In that vein, an unintentionally humorous moment in Zenovich’s film comes in the segment on Operatión Puerto, in which Spanish police raided the lab of a sports physiologist named Eufemiano Fuentes, whose secret code for the drugs and blood bags of athletes consisted of their initials or, in the case of Jan Ullrich, his first name. But from the time that Lance said he started doping in 1993 through his first Tour victory in 1999, he didn’t have the extensive resources that victory and fame subsequently brought him. And surely the president of the Union Cycliste International (the UCI, the sport’s governing body), Hein Vergruggen, carries some moral accountability for turning a blind eye to the corruption he not only could not have failed to notice, but actively participated in covering it up in the name of saving his sport after the catastrophic 1998 Tour that exposed the massive doping scandal already underway while Lance was still struggling to come back from cancer and chemotherapy.

It is not unreasonable to argue that the playing field wasn’t level, but it isn’t now and never was level, drugs or no drugs. Genetically gifted riders with a fire in the belly to win and the discipline to train 500 miles a week accrue not only superior fitness but greater resources in the form of more sponsorship dollars, faster support riders, smarter coaches and managers, better training facilities, food, and other creature comforts. For example, the well-capitalized British Team Sky would rent out rooms on Mount Teide in Tenerife in the Canary islands for the entire year so that their team members could train at altitude, a legal method of increasing oxygen-rich blood cells. The real victims of doping are not the other top riders whom Lance beat (all of whom doped), but the athletes who DNF’d, finished near the bottom of the leaderboard, or gave up their dream and went home to get a real job. For that you can blame systemic corruption of the system and the logical deterioration of norms of fairness that follow from it, more than any single cyclist no matter how much they capitalized on it.

Breaking the Chain

At the end of my Scientific American article I suggested that in order to reform cycling and encourage cyclists to play by the rules, the expected values of the doping game had to be changed. For example, building and enforcing a much stricter drug-testing regimen would dramatically increase the likelihood of getting caught, thereby tilting the matrix incentive toward riding clean; for those who want to risk getting caught, increasing the penalty for doping from a temporary to a lifetime ban on competing would presumably nudge the motivation toward fair play even further.

I also suggested granting immunity to athletes for past cheating if they come clean about how doping programs worked; increase the number of competitors tested, both in competition and out-of-competition; disqualify all team members from an event if any member of the team tests positive for doping, thereby shifting the taboo on doping from an external governing body to the internal workings of the team and its members; and compel any convicted athlete to return all salary paid and prize monies earned to the team sponsors, further strengthening the incentive for athletes to enforce their own antidoping rules.

Since 2008 anti-doping controls have improved dramatically with some of these factors implemented, plus others, most notably a “biological passport,” in which an athlete’s fitness indicators are constantly monitored, such as HCT, power output, VO2 maximum rate of oxygen consumption, and others, so that any spike in improvement beyond what training can account for is an indicator of possible doping. In his 2019 book, One-Way Ticket, Jonathan Vaughters explains in game-theory language that the biological passport “wasn’t about catching people. It was always about dissuading them. It’s about limiting them. It’s about keeping things fair.” Fairness is what athletes want more than anything and Vaughters is concerned that the moralizing impulse to “find evildoers and burn them at the stake” is “what the world wants from anti-doping” but is counterproductive to the deeper fairness issue — the level playing field in which other factors like talent, training, nutrition, and drive determine outcomes. Now a team manager and cycling influencer, Vaughters has been vocal and public about his teams riding clean, thereby shifting the norms of the sport from “everyone’s doing it” to “some aren’t doing it” in hopes of arriving at a new norm of “no one’s doing it.”

Jonathan Vaughters

Forgiveness and Redemption

At the end of Vaughters’ memoir he admits “We all doped. It’s inexcusable and it’s a fact.” It should be clear by now that Lance’s downfall has less to do with doping and more to do with the people whose lives he harmed in his years of denial, defense, and destruction of others. As Vaughters put it: “The bullying was the reason Lance paid a higher price than the rest of us.” One of those who feels bullied is Betsy Andreu, wife of Lance’s teammate of many years, Frankie Andreu. A deeply moral person who is the very the embodiment of Kantian deontological (rule-bound) ethics, Betsy does not suffer cheats gladly (including her husband, whom she upbraided when she discovered he doped just to compete). She explained to me in no uncertain terms exactly what the core issue with Lance is and what he has to do to redeem himself.

First, she said, the other dopers, such as Ullrich, Basso, and Pantani, did not try to destroy other people for simply telling the truth about what was going on. Doping causes harm to others in the sport who don’t dope, but attacking, suing, libeling, and curtailing the income of those attempting to expose the doping is another level of harm altogether. Second, she continued, there is the matter of apologies. “I’ve learned there are 3 components to being sorry,” she outlined:

- You acknowledge the wrong you did to the person you wronged.

- You apologize for it.

- You make amends. How? You ask the person what they need from you to show you they mean they’re sorry.

Betsy Andreu

Restorative vs. Retributive Justice

In criminal justice scholarship what Betsy Andreu is proposing is called restorative justice, in which the perpetrator apologizes for the offense, attempts to set-to-rights the wrong done, and if possible initiate or restore good relations with the victim. Restorative justice is contrasted with retributive justice, in which wrong doers should get their just desserts. Think Old Testament eye-for-an-eye (Moses) vs. New Testament turn-the-other-cheek (Jesus), Malcolm X vs. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rambo vs. Gandhi. Redemption begins with an acknowledgment on the part of the wrongdoer, who must take some level of responsibility for the offense, and builds from there to include the victims’ losses and a plan for restoration. As I outlined in my chapter on the subject in The Moral Arc, retributive justice is focused on what offenders deserve whereas restorative justice is concerned about what victims need; retributive justice is about what was done wrong whereas restorative justice is about making it right; retributive justice is offender oriented whereas restorative justice is victim oriented.

I don’t know who all feels that they should be on Lance’s restorative justice list. And, clearly, there are possible legal and financial consequences of going down that path that I do not know about. But in noting the many cancer victims and their families Lance inspired and materially helped through his charitable generosity — highlighted in the film and praised as unassailably real by ESPN’s Senior Writer Bonnie Ford, who was otherwise a harsh critic — it is evident that Armstrong is capable of being a person who can make a positive difference in the world. Will he?

This could be Lance’s greatest challenge, harder perhaps even than overcoming cancer, inasmuch as personality and temperament are relatively stable throughout the lifespan. I don’t know if he has the character to do so across the board, but he has made amends with some people, and I will note that many a person with far graver personal failings have turned their lives around so dramatically that they’re almost unrecognizable. A type specimen might be the heavyweight boxing champion George Foreman, who by his own account was, pace Landis’ description of Armstrong, a badass motherfucker … until he was humbled by Muhammad Ali in the Rumble in the Jungle. Foreman willed himself into becoming one of the most likeable and inspirational figures of the late 20th century, recapturing his heavyweight title along with the admiration of millions. Others have made similar transformations. Can Lance do the same? The only person standing in the way is Lance himself. We shall see. ![]()

About the Author

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, host of the Science Salon podcast, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University. He is the author of a dozen books including the New York Times bestsellers Why People Believe Weird Things, The Believing Brain, and The Moral Arc. His latest book is Giving the Devil His Due. He is also a co-founder of the 3,000-mile nonstop transcontinental bicycle Race Across America (RAAM), which he competed in 5 times and was the Race Director for a decade.

This article was published on May 31, 2020.

The psyschology of athletes is not going to change. They will not rat out their teammates unless they themselves are in a position of peril, that is until they have failed a test. If they are still in the sport, they destroy team morale and their own repute with their own or other teams, and if they are out of the sport they just aren’t believed. The key will always be testing, and crackdowns by authorities outside the sport. The sports federations themselves have too much to lose by exposing widespread doping and usually won’t act until the public gets disturbed by obvious doping.

Looking forward to seeing these documentaries. But appreciated this somewhat more realistic take on Armstrong and a more realistic perspective on him and his times. At times I’ve been appalled at the hypocrisy of various players who are now “shocked . . . shocked! . . . that doping was going on here.” Give me a break. There is no way that Armstrong’s confessions are actually going to damage his sponsors and it’s certainly not going to cost them the tens of millions they made while he was winning.

As for sports fans, yes, I understand the disillusionment that the fantasy of this cancer-beating superman wasn’t exactly true. However, the reality is that most of us experienced unprecedented thrills by watching Armstrong’s victories and the subsequent disillusionment may make us disappointed that the fairy tale wasn’t real, but it can’t actually remove our experience of all those thrills.

Yes, his bullying crossed the line and he needs to make reparation for that. But the doping? When it was simply the context in which he was operating? Sheesh. Did we really have our collective purity violated by all that? Armstrong did what most highly-driven, top of their sports figures do: he got away with what he could get away with. I think the outrage about Armstrong says much more about us, societally, than it does about him.

Best article on the subject I have ever read. Sometimes I wonder if at the End of the day Lance have done more good than bad (Intentionally or not). Sure he deeply hurt “many” people (10, 50 , 100?) but Livestrong raised over 500 million dollars and helped thousands navigate cancer. He took the sport to a new high in America and inspired millions of cancer survivors in a way that not other public figure has. Like it or not, most of today’s haters are a product of the Lance era. Is just that simple.

“. An autopsy revealed a pharmacopoeia of drugs in his body and a vile of amphetamines in his jersey pocket”.

Got this far – made me realise the author doesn’t know what he’s talking about. 1. Tom Simpson’s autopsy revealed amphetamines and alcohol. 2. I don’t think you need an autopsy to “reveal” amphetamines in his jersey pocket.

Slack.

Shall we fact-check the rest of this article…?

Doping doesn’t make the playing field “level,” it benefits those more who have naturally lower hematocrit:

“Take two riders of the same age, height, and weight, says Vaughters. They have identical VO2max at threshold—a measure of oxygen uptake at the limit of sustainable aerobic power. But one of them has a natural hematocrit of 36 and one of 47. Those riders have physiologies that don’t respond equally to doping.

“It’s not even a simple math equation that, with the old 50 percent hematocrit limit, one rider could gain 14 percent and another only three. Even if you raise the limit to the edge of physical sustainability, 60 percent or more, to allow both athletes significant gains, it’s not an equal effect, Vaughters says.

“He goes on to explain that the largest gains in oxygen transport occur in the lower hematocrit ranges—a 50 percent increase in RBC count is not a linear 50 percent increase in oxygen transport capability. The rider with the lower hematocrit is actually extremely efficient at scavenging oxygen from what little hemoglobin that he has, comparatively. So when you boost his red-cell count, he goes a lot faster. The rider at 47 is less efficient, so a boost has less effect.

“You have guys who train the same and are very disciplined athletes, and are even physiologically the same, but one has a quirk that’s very adaptable to the drug du jour,” Vaughters says. “Then all of a sudden your race winner is determined not by some kind of Darwinian selection of who is the strongest and fittest, but whose physiology happened to be most compatible with the drug,”

https://www.bicycling.com/racing/a20016616/garmin-insider-21/

Great article. Only thing I wondered having read it, and you know far more about this than I do, was whether the “everyone was doing it and Armstrong was just the best cyclist” theory takes account of the Festina affair in 1998. Ullrich and Pantani are the two strongest riders, there’s a huge doping scandal in 1998, a lot of people get scared, and suddenly the next year Armstrong, a good but not great cyclist, is utterly dominant and remains so for nearly a decade.

Isn’t the parsimonious explanation for this that everyone else actually did reduce their doping, and Armstrong redoubled his commitment to it? That Armstrong really is an example of someone winning by cheating more than their competitors?

Again, fantastic article, thank you.

If ‘all’ the riders were doping, then the race was fair. What’s the problem????