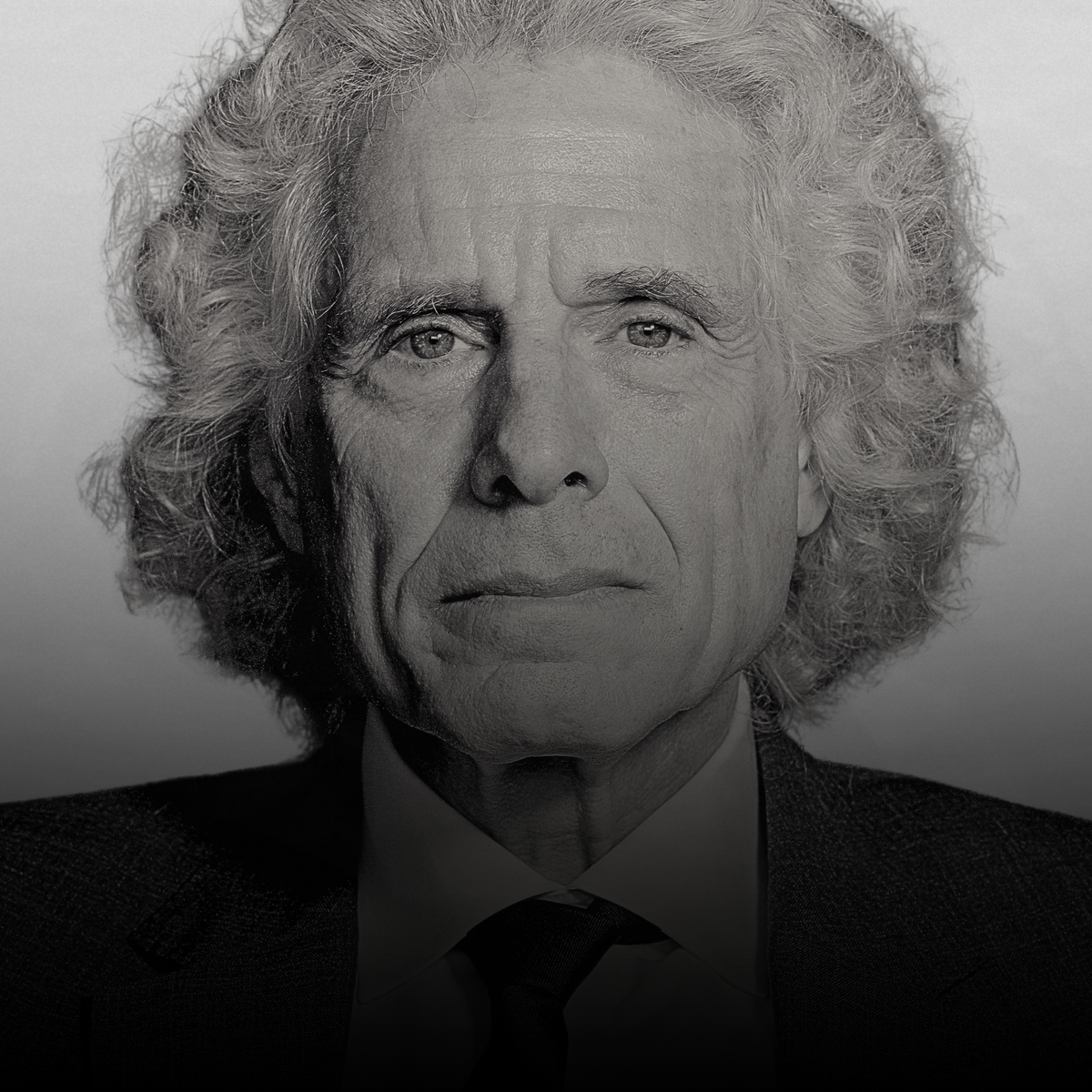

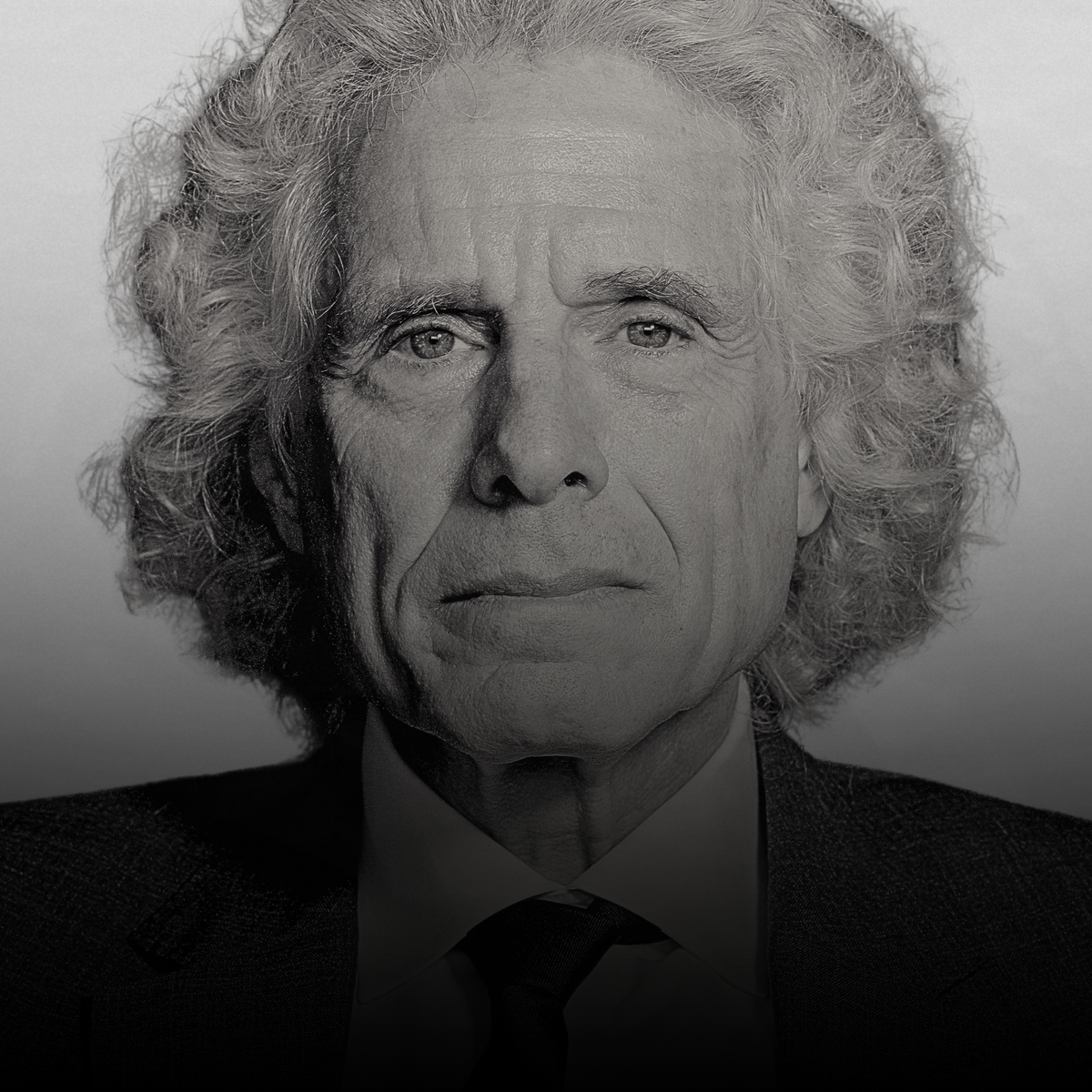

The Power of Common Knowledge: Steven Pinker on Language, Norms, and Punishment

New episode of the podcast. Listen now.

New episode of the podcast. Listen now.

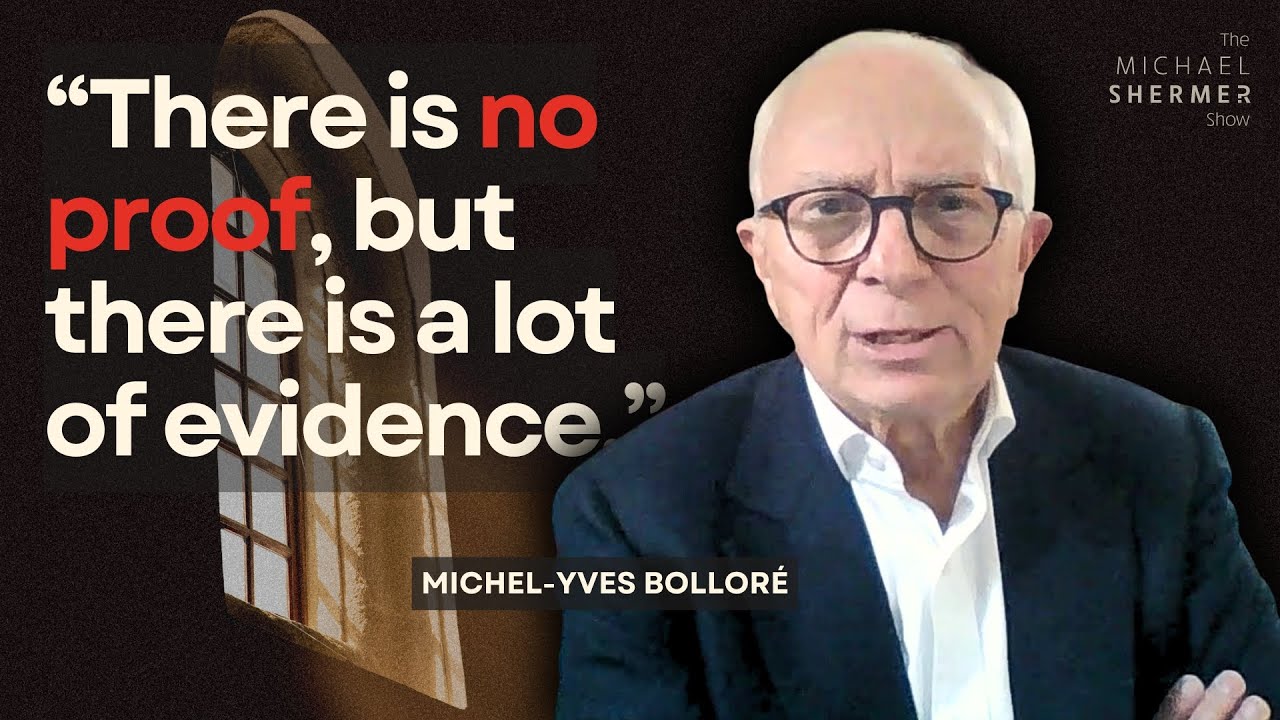

The Michael Shermer Show is a series of long-form conversations between Dr. Michael Shermer and leading scientists, philosophers, historians, scholars, writers, and thinkers about the most important issues of our time.

The Michael Shermer Show is a series of long-form conversations between Dr. Michael Shermer and leading scientists, philosophers, historians, scholars, writers, and thinkers about the most important issues of our time.

Get the latest in science, skepticism, and societal analysis—delivered straight to your inbox.

The Skeptic Research Center (SRC) offers clear, single-topic analyses of proprietary polling and survey data to reveal public attitudes on key issues. To empower you with a deeper understanding of what your fellow citizens really believe and how they really behave.

To explore complex issues with careful analysis and help you make sense of the world. Nonpartisan. Reality-based.

About Skeptic Magazine