Jonestown: Cult Dynamics and Survivorship

Annie Dawid’s most recent novel revisits the Jonestown Massacre from the perspective of the people who were there, taking the spotlight off cult leader Jim Jones and rehumanizing the “mindless zombies” who followed one man from their homes in the U.S. to their death in Guyana, but as our notion of victimhood is improving, we’re also forced to confront the ugly truth: In the almost fifty years since Jonestown: large-scale cult-related death has not gone away.

On the 18th of November, 2024, fiction author Annie Dawid’s sixth book, Paradise Undone: A Novel of Jonestown, celebrated its first birthday on the same day as the forty-sixth anniversary of its subject matter, an incident that saw the largest instance of intentional U.S. citizen death in the 20th Century and introduced the world to the horrors and dangers of cultism—The Jonestown Massacre.

A great deal has been written on Jonestown after 1978, although mostly non-fiction, and the books Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People (1982) and The Road to Jonestown: Jim Jones and Peoples Temple (2017) are considered some of the most thorough investigations into what happened in the years in the lead up to the massacre. Many historical and sociological studies of Jonestown focus heavily on the psychology and background of the man who ordered 917 men, women, and children to die with him in the Guyanese jungle—The Reverend Jim Jones.

For cult survivors beginning the difficult process of unpacking and rebuilding after their cult involvement—or for those who lose family members or friends to cult tragedy—the shame of cult involvement and the public’s misconception that cult recruitment stems from a psychological or emotional fault are challenges to overcome.

And when any subsequent discussions of cult-related incidents can result in a disproportionate amount of attention given to cult leaders, often classified as pathological narcissists or having Cluster-B personality disorders, there’s a chance that with every new article or book on Jonestown, we’re just feeding the beast—often at the expense of recognizing the victims.

Annie Dawid, however, uses fiction to avoid the trap of revisiting Jonestown through the lens of Jones, essentially removing him and his hold over the Jonestown story.

“He’s a man that already gets too much air time,” she says, “The humanity of 917 people gets denied by omission. That’s to say their stories don’t get told, only Jones’ story gets told over and over again.”

“I read so many books about him. I was like enough,” she says, “Enough of him.”

Jones of Jonestown

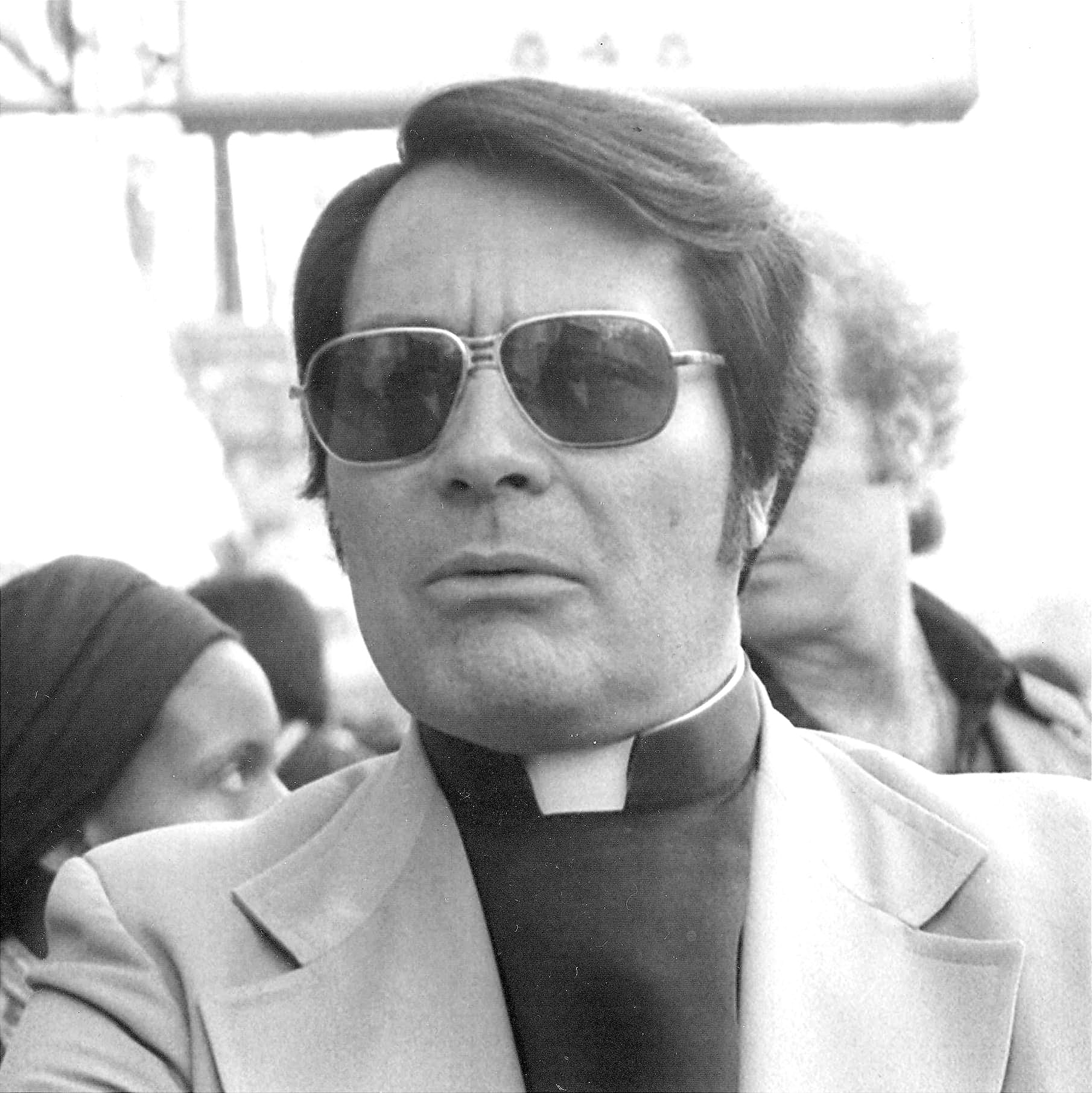

By all accounts, Jones, in his heyday, was a handsome man.

An Internet image search for Jones pulls up an almost iconic, counter-culture cool black-and-white photo of a cocksure man in aviator sunglasses and a dog collar, his lips parted as if the photographer has caught him in the middle of delivering some kind of profundity.

Jones’s signature aviator sunglasses may have once been a fashion statement, a hip priest amongst the Bay Area kids, but now he never seems to be without them as an increasing amphetamine and tranquilizer dependency has permanently shaded the areas under his eyes.

“Jim Jones is not just a guy with an ideology; he was a preacher with fantastic charisma, says cult expert Mike Garde, the director of the Irish charity Dialogue Ireland, an independent charity that educates the public on cultism and assists its victims. “And this charisma would have been unable to bring people to Guyana if he had not been successful at doing it in San Francisco,” he adds.

Between January 1977 and August 1978, almost 900 members of the Peoples Temple gave up their jobs, and life savings, and left family members behind in the U.S. to relocate to Guyana to begin moving into the new home: Peoples Temple Agricultural Mission, an agricultural commune inspired by Soviet socialist values.

On November 19th, 1978, U.S. Channel 7 interrupted its normal broadcast with a special news report, and presenter Tom Van Amburg encouraged viewer discretion and described the horror of hardened newsmen upon seeing the scenes at Jonestown that had “shades of Auschwitz.”

As a story, the details of Jonestown feel like a work of violent fiction, like a prototype Cormac McCarthy novel: A Hearts of Darkness-esque cautionary tale of Wild-West pioneering gone wrong in a third-world country with Jones cast in the lead role.

“I feel like there’s a huge admiration for bad boys, and if they’re good-looking, that helps too,” Dawid says, “This sort of admiration of the bad boy makes it that we want to know, we’re excited by the monster—we want to know all about the monster.”

Dawid understands Jones’ allure, his hold over the Jonestown narrative as well as the public’s attention, but “didn’t want to indulge that part of me either,” she says.

“But I wasn’t tempted to because I learned about so many interesting people that were in the story but never been the subjects of the story,” she adds, “So I wanted to make them the subjects.”

The People of the Peoples Temple

For somebody who was there from the modest Pentecostal beginnings of the Peoples Temple in 1954 until the end in Guyana, very little attention had ever been paid to Marceline Jones in the years after Jonestown.

“She was there—start to finish. For me, she made it all happen, and nobody wrote anything about her,” Dawid says, “The woman behind the man doesn’t exist.”

Even for Garde, Marceline was another anonymous victim of no significance beyond the surname connecting her to the husband: “My initial read of Marceline was that she was ‘Just a cipher, she wasn’t a real person,” he says, “She didn’t even register on my dial.”

Dawid gives Marceline an existence, and in her book, she’s a “superwoman” juggling her duties as a full-time nurse and the Peoples Temple—a caring, selfless individual who lives in the service of others, mainly the children and the elderly of the Peoples Temple.

“In the sort of awful way, she’s this smart, interesting, energetic woman, but she can’t escape the power of her husband,” Dawid says, “It’s just very like domestic violence where the woman can’t get away from the abuser [and] I have had so much feedback from older women who felt that they totally related to her.”

The woman behind the man doesn’t exist.

Selfless altruism was a shared characteristic of the Peoples Temple, as members spent most of their time involved in some kind of charity work, from handing out food to the homeless or organizing clothes drives.

“You know, I did grow to understand the whole sort of social justice beginnings of Peoples Temple,” Dawid says, “I came to admire the People’s Temple as an organization.”

“Social justice, racism, and caring for old people, that was a big part of the Peoples Temple. And so it made sense why an altruistic, smart, young person would say, ‘I want to be part of this,’” she adds.

Guyana

For Dawid, where it all went down is just as important—and arguably just as overlooked in the years after 1978—as the people who went there.

Acknowledging the incredible logistical feat of moving almost 1000 people, many of them passport-less, to a foreign country, Dawid sees the small South American country as another casualty of Jonestown: “I had to have a Guyanese voice in my book because Guyana was another victim of Jones,” Dawid says.

The English-speaking Guyana—recently free of British Colonial rule and leaning towards Socialism under leader Cheddi Jagan—offered Jones a haven from the increasing scrutiny back in the U.S. amidst accusations of fraud and sexual abuse, and was “a place to escape the regulation of the U.S. and enjoy the weak scrutiny of the Guyanese state,” according to Garde.

“He was not successful at covering up the fact he had a dual model: he was sexually abusing women, taking money, and accruing power to himself, and he had to do it in Guyana,” Garde adds, “He wanted a place where he could not be observed.”

There may be a temptation to overstate what happened in 1978 as leaving an indelible, defining mark on the reputation of a country during its burgeoning years as an independent nation, but in the columns of many newspapers on the breakfast tables of American households in the years afterward, one could not be discussed without the other: “So it used to be that if you read an article that mentioned Guyana, it always mentioned Jonestown,” Dawid says.

In the few reports interested in the Guyanese perspective after Jonestown, the locals have gone through a range of feelings from wanting to forget the tragedy ever happened, or turning the site into a destination for dark tourism.

However, the country’s 2015 discovery of offshore oil means that—in the pages of some outlets and the minds of some readers—Jonestown is no longer the only thing synonymous with Guyana: “I read an article in the New York Times about Guyana’s oil,” Dawid says, “and it didn’t mention Jonestown.”

Victimhood to Survivorship

According to Garde, the public’s perception of cult victims as mentally defective, obsequious followers, or—at worst—somehow deserving of their fate is not unique to victims of religious or spiritual cults.

“Whenever we use the words ‘cult’, ‘cultism’ or ‘cultist’ we are referring solely to the phenomenon where troubling levels of undue psychological influence may exist. This phenomenon can occur in almost any group or organization,” reads Dialogue Ireland’s mission statement.

“Victim blaming is something that is now so embedded that we take it for granted. It’s not unique to cultism contexts—it exists in all realms where there’s a victim-perpetrator dynamic,” Garde says, “People don’t want to take responsibility or face what has happened, so it can be easier to ignore or blame the victim, which adds to their trauma.”

While blaming and shaming prevent victims from reporting crimes and seeking help, there does seem to be recent improvements in their treatment, regardless of the type of abuse:

“We do seem to be improving our concept of victims, and we are beginning to recognize the fact that the victims of child sexual abuse need to be recognized, the #MeToo movement recognizes what happened to women,” says Garde, “They are now being seen and heard. There’s an awareness of victimhood and at the same time, there’s also a movement from victimhood to survivorship.”

Paradise Undone: A Novel of Jonestown focuses on how the survivors process and cope with the fallout of their traumatic involvement with or connection to Jonestown, making the very poignant observation that cult involvement does not end when you escape or leave—the residual effects persist for many years afterward.

“It’s an extremely vulnerable period of time,” Garde points out, “If you don’t get out of that state, in that sense of being a victim, that’s a very serious situation. We get stuck in the past or frozen in the present and can’t move from being a victim to having a future as a survivor.”

Support networks and resources are flourishing online to offer advice and comfort to survivors: “I think the whole cult education movement has definitely humanized victims of cults,” Dawid points out, “And there are all these cult survivors who have their own podcasts and cult survivors who are now counseling other cult survivors.”

At the very least, these can help reduce the stigma around abuse or kickstart the recovery process; however, Garde sees a potential issue in the cult survivors counseling cult survivors dynamic: “There can be a danger of those operating such sites thinking that, as former cult members, they have unique insight and don’t recognize the expertise of those who are not former members,” he says, “We have significant cases where ex-cultists themselves become subject to sectarian attitudes and revert back to cult behavior.”

Whenever we use the words ‘cult’, ‘cultism’ or ‘cultist’ we are referring solely to the phenomenon where troubling levels of undue psychological influence may exist.

And while society’s treatment and understanding of cult victims may be changing, Garde is frustrated with the overall lack of support the field of cult education receives, and all warnings seem to fall on deaf ears, as they once were in the lead up to Jonestown:

The public’s understanding seems to be changing, but the field of cult studies still doesn’t get the support or understanding it needs from the government or the media. I can’t get through to journalists and government people, or they don’t reply. It’s so just unbelievably frustrating in terms of things not going anywhere.

One fundamental issue remains; some might say that things have gotten worse in the years post-Jonestown: “The attitude there is absolutely like pro-survivor, pro-victim, so that has changed,” Dawid says, “You know, it does seem like there are more cults than ever, however.”

A History of Violence

The International Cultic Studies Association’s (ICSA) Steve Eichel estimates there are around 10,000 cults operating in the U.S. alone. Regardless of the number, in the decades since Jonestown, there has been no shortage of cult-related tragedies resulting in a massive loss of life in the U.S. and abroad.

The trial of Paul Mackenzie, the Kenyan pastor behind the 2023 Shakahola Forest Massacre (also known as the Kenyan starvation cult), is currently underway. Mackenzie pleads not guilty to the death of 448 people and charges of murder, child torture, and terrorism as Kenyan pathologists are still working to identify all of the exhumed bodies.

“It’s frustrating and tragic to see events like this still happening internationally, so it might seem like we haven’t progressed in terms of where we’re at,” Garde laments.

Jonestown may be seen as the progenitor of the modern-cult tragedy, an incident for which other cult incidents are compared, but for Dawid, the 1999 Colorado shooting that left 13 teenagers dead and 24 injured would shock American society in the same way, and leave behind a similar legacy.

“I see a kind of similarity in the impact it had,” Dawid says, “Even though there had been other school shootings before Columbine….I think it did a certain kind of explosive number on American consciousness in the same way that Jones did, not just on American consciousness, but world consciousness about the danger of cults.”

Victim blaming is something that is now so embedded that we take it for granted.

Just as everyone understands that Jonestown refers to the 917 dead U.S. citizens in the Guyanese jungle, the word “Columbine” is now a byword for school shootings. However, if you want to use their official, unabbreviated titles, you’ll find both events share the same surname—massacre.

“All cult stories will mention Jonestown, and all school shootings will [mention] Columbine,” Dawid points out.

In Memoriam

The official death toll on November 18, 1978, is 918, but that figure includes the man who couldn’t bring himself to follow his own orders.

According to the evidence, Jim Jones and the nurse Annie Moore were the only two to die of gunshot wounds at Jonestown. The entry wound on Jones’ left temple meant there was a very good chance the shooter wasn’t right-handed (as Jones was). It is believed that Jones ordered Moore to shoot him first, confirming for Garde, Jones’ cowardice: “We saw his pathetic inability to die as he set off a murder-suicide. He could order others to kill themselves, but he could not take the same poison. He did not even have the guts to shoot himself.”

On the anniversary of Jonestown (also International Cult Awareness Day), people gather at the Jonestown Memorial at the Workers at the Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California, but the 2011 unveiling of the memorial revealed something problematic. Nestled between all the engraved names of the victims is the name of the man responsible for it all: James Warren Jones.

The inclusion of Jones’ name has outraged many in attendance, and there are online petitions calling for it to be removed. Garde agrees, and just as Dawid retired Jones from his lead role in the Jonestown narrative, he believes Jones’ name should be physically removed from the memorial.

“He should be definitely excluded and there should be a sign saying very clearly he was removed because of the fact that it was totally inappropriate for him to be connected to this.” he says, “It’s like the equivalent of a murderer being added as if he’s a casualty.”

In the years since she first started researching the book, Dawid feels that the focus on Jones: “There’s been a lot written since then, and I feel like some of the material that’s been published since then has tried to branch out from that viewpoint,” she says.

It’s frustrating and tragic to see events like this still happening internationally.

Modern re-examinations challenge the long-time framing of Jonestown as a mass suicide, with “murder-suicide” providing a better description of what unfolded, and the 2018 documentary Jonestown: The Women Behind the Massacre explores the actions of the female members of Jones’ inner circle.

While it may be difficult to look at Jonestown and see anything positive, with every new examination of the tragedy that avoids making him the central focus, Jones’ power over the Peoples Temple, and the story of Jonestown, seems to wane.

And looking beyond Jones reveals acts of heroism that otherwise go unnoticed: “The woman who escaped and told everybody in the government that this was going to happen. She’s a hero, and nobody listened to her,” Dawid says.

That person is Jonestown defector Deborah Layton, the author of the Jonestown book Seductive Poison, whose 1978 affidavit warned the U.S. government of Jones’ plans for a mass suicide.

And in the throes of the chaos of November 18, a single person courageously stood up and denounced the actions that would define the day.

For Christine, who refused to submit.

Dawid’s book is dedicated to the memory of the sixty-year-old Christine Miller, the only person known to have spoken out that day against the Jones and his final orders. Her protests can be heard on the 44-minute “Death Tape”—an audio recording of the final moments of Jonestown.

The dedication on the opening page of Paradise Undone: A Novel of Jonestown reads: “For Christine, who refused to submit.”

Perceptions of Jonestown may be changing, but I ask Dawid how the survivors and family members of the victims feel about how Jonestown is represented after all these years.

“It’s a really ugly piece of American history, and it had been presented for so long as the mass suicide of gullible, zombie-like druggies,” Dawid says, “We’re almost at the 50th anniversary, and the derision of all the people who died at Jonestown as well as the focus on Jones as if he were the only important person, [but] I think they’re encouraged by how many people still want to learn about Jonestown.”

“They’re very strong people,” Dawid tells me.