Black Lives Matter vs. Black Lives Saved: The Urgent Need for Better Policing

To paraphrase Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, Black Lives Matter activists and police unions are two houses both alike in indignity. Neither truly wants to improve policing in the most necessary ways: the former because it could undermine their view of the world and reduce revenue streams, including billions in donations; the latter for a more mundane reason. Cops, like other street-level bureaucrats, don’t want to change their standard operating procedures and face accountability for screwups. Unfortunately, with Black Lives Matter groups receiving billions in donations and helping increase progressive turnout, media and academia failing to provide accurate information to voters, and police unions enjoying iconic status among conservatives when they are better viewed as armed but equally inefficient teachers’ unions, we don’t see the political incentives for reform any time soon, despite some recent local level successes.

Injustice—How Progressives (and Some Conservatives) Got Us Into This Mess

Professors and other respectables rail against “deplorables,”1 but missing in political discourse is that mass rule, AKA populism, is not a mass pathological delusion. Rather, its appearance is for solid economic and social reasons. When problems that affect regular citizens get ignored by their leaders, people in democratic systems can get revenge at the ballot box. From inflation and foreign policy debacles, to COVID-19 school shutdowns that went on far longer in the U.S. than in Europe at immense and immensely unequal social cost,2 ordinary people sense that the wealthy, bureaucrats, professionals, and professors often advance their own interests and fetishes at the expense of regular folks, and then use mainstream “knowledge producing” institutions, particularly academia and the mainstream news media, to cover up their failings.

Indeed, as Newsweek’s Batya Ungar-Sargon shows in her brilliant book Bad News: How Woke Media Is Undermining Democracy, the mainstream media now stand forthrightly behind the plutocrats. This can be documented empirically: the Center for Public Integrity points out that, during the 2016 presidential race, identified mainstream media journalists made 96 percent of their financial donations to one political party (the Democrats) and to the more mainstream of the candidates running.3 That basic instinct to hold the respectables accountable for their failings may have been the only thing keeping the Trump 2024 presidential candidacy viable despite his many and well-documented failings and debate loss against Kamala Harris.4

Perhaps nowhere is popular anger more justifiable than regarding crime, a trend best captured in the saga of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. The roots of that failure go deep, and implicate multiple sacred cows in contemporary elite politics. As Anglo-Canadian political scientist Eric P. Kaufmann writes in his landmark work The Third Awokening,5 critical theory and other postmodern ideologies (AKA woke) have been evolving for over a century. To his credit, and unlike most conservatives, Kaufmann does not paint wokeism as entirely wrong—like populism, it too came about as a result of grievances experienced by the wider society. Rather, he describes it as needing moderating influences because, as with all other ideologies, it is not entirely (or in this case even mainly) correct. This is all the more so since so many among the woke, who are vastly overrepresented in the political class, lack experience with people from different walks of life. Their insulation, which Democratic commentator and political consultant James Carville—who coined the phrase “it’s the economy, stupid” that was key to then-Governor Bill Clinton’s 1992 victory over President George H.W. Bush—derides as “faculty lounge politics,”6 promotes fanaticism, declaring formerly extreme ideas not merely contestable or even mainstream, but off limits to criticism.

The nonnegotiable assumptions of late-stage woke include reflexively disparaging the achievements of Western civilization, while anointing non-Western or traditionally marginalized peoples and ideas as sacred. This deep script makes those (particularly wealthy Whites)7 with advanced degrees susceptible to believing the worst about White police officers, leaving influential segments of the political class subject to exploitation by grifters, with disastrous results. As one of us shows, many Americans believe that police pose a near genocidal threat to Black people, when in fact in a typical year fewer than 20 unarmed Black people (some of whom were attacking the police) are killed by nearly a half million White police officers, a lot lower than one would expect given that the Black crime rate is more than double that of other cohorts.8 Likewise, The 1619 Project creator Nikole Hannah-Jones and many other activists claim that police departments evolved from racist slave-catching patrols, which is simply not true.9

The problem arises when the Pulitzer Prize-winning Hannah-Jones and many other scholars and activists have an interest in maintaining the assertion that police are a threat to Black people, employing shocking visual images and taking advantage of widespread ignorance to make the case. The PBS News Hour, like other media outlets, has constantly highlighted the very rare instances in which White police officers actually do kill unarmed Black people, without ever placing them in the context of overall statistical evidence, which demonstrates that these tragic events are incredibly rare, nor giving comparable treatment to the far more numerous White casualties of police.10

Since the Black Lives era began, fatal ambushes of police officers have risen dramatically, almost certainly due to demonizing of the police.

Academia is an even greater offender. At the opening plenary of the 2021 American Educational Research Association annual meeting, AERA President Shaun Harper spent most of his hour-long session lambasting police as a threat to Black people. Harper is a master at securing grants and climbing the hierarchy to run academic associations. Yet his views on cops are out of sync with both reality and with the views of Black voters, who have consistently refused to support defunding police, and whose opinions on criminal justice generally resemble those of Whites and Hispanics.11, 12

Harper’s views do, however, reflect the Critical Race Theory (CRT) approaches preferred by professors studying race, both in education and in the social sciences more broadly—24 of the 25 most cited works with Black Lives Matter in their titles do not involve research that would save Black lives in any conceivable time frame. The 19th most cited article does empirically study (and suggest better) police procedures, making a case for having police document their actions in writing not just every time they fire their guns, but every time they unholster them. This mere reform, likely forcing cops to think an extra second before acting, reduces police shootings of civilians without increasing casualties among officers.13 In sharp contrast, however, other highly cited “scholarly” articles on Black Lives Matter:

… explore social media use and activism (4, including one piece involving Ben and Jerry’s ice cream and BLM), racial activism and white attitudes (3), immigration and migrants (2), anti-Blackness in higher education, “democratic repair,” radically re-imagining law, anti-Blackness of global capital, urban geography, counseling psychology, research on K–12 schools, BLM and “technoscientific expertise amid solar transitions,” BLM and “evidence based outrage in obstetrics and gynecology,” and BLM and differential mortality in the electorate.14

It is probably worth repeating here that at least one article, written by senior academics at respected institutions, looks specifically at the influence of the Black Lives Matter movement on the naming of popular ice cream flavors at Ben and Jerry’s. These “studies” get professors tenure, grants, and notoriety, but will not save Black (or any) lives in any conceivable time frame.

Sometimes academia allies with progressive politicians. As Harvard University-affiliated Democratic pollster John Della Volpe boasted at a recent political science conference,15 Black Lives Matter offers dramatic symbols that can measurably increase progressive voter turnout. Left unsaid was that the dominant BLM narrative both misleads voters and gets Black people killed—or that questioning it can be risky. This tension likely explains why, after careful, peer-reviewed empirical research by economist Roland Fryer found that controlling for suspect behavior, police do not disproportionately kill Black people (White suspects were in fact 27 percent more likely to be shot), then-Harvard University President Claudine Gay tried to fire Fryer.

She accused the tenured professor, an African- American academic star, of the use of inappropriate language, an offense for which Harvard’s own policies dictated sensitivity training. Fryer’s published findings were likely seen as attacking “sacred” beliefs and threatening external grants received on the premise of overwhelming police racism.16 As renegade journalist Batya Ungar-Sargon shows, the same dynamic holds in newsrooms, where reporting on Black Lives Matter’s spectacular failures to save Black (and other) lives is a firing offense.17 Indeed, were we not tenured professors at public universities in the South, we could likely get in trouble for writing essays like this one.

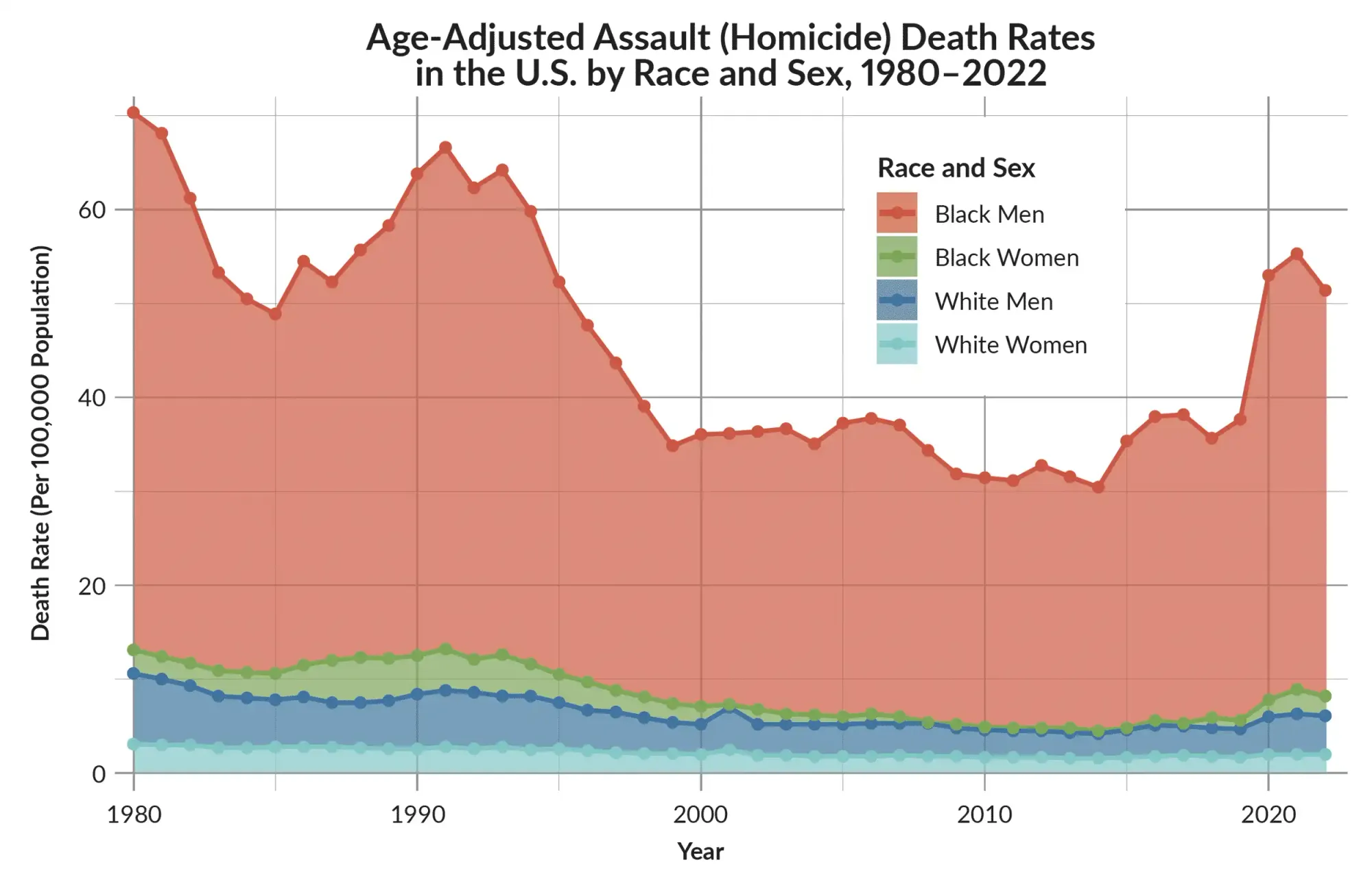

So what if progressives use anti-police demagoguery to win a few elections and grants? Isn’t that just election campaign “gamesmanship?” Does that hurt anyone? Yes, it does. Since the Black Lives era began, fatal ambushes of police officers have risen dramatically, almost certainly due to demonizing of the police. More importantly, Black Lives Matter de-policing policies seem to have taken thousands of (mainly Black) lives.18 During the BLM era, dated here as beginning in 2012, the age-adjusted Black homicide rate has almost doubled, rising from 18.6 murders per 100,000 African-American citizens in 2011 to 32 murders per 100,000 in 2021.19 Murders of Black males rose to an astonishing peak of 56/100,000 during this period (in 2021), while Black women (9.0/100,000) came to “boast” a higher homicide rate than White men (6.4) and all American men (8.2).

Yet for all our lambasting of Black Lives Matter, police unions and leaders have not covered themselves in glory in the BLM era, largely supporting precinct level decisions to de-police the dangerous parts (“no-go”- or “slow-go”-zones) of major cities, and refusing to support reforms that do cut crime but discomfort cops. Astonishingly, high homicide rates have little or no impact on whether police commissioners keep their jobs, giving cops few incentives to do better rather than just well enough.20

On the positive side, the political system is starting to respond to public anger from the increased crime and disorder of the Black Lives Matter era. In its presidential transition, the Biden administration largely sidelined the BLM portions of its racial reckoning agenda—even as it poured money into counterproductive and arguably racist DEI initiatives.21 More impactful responses came at the level of major city governments, which are those most affected by crime and disorder. Across progressive cities such as Seattle, Portland, and New York and less progressive cities like Philadelphia and Dallas, voters have started distancing themselves from Black Lives Matter policies. For the first time in decades, Seattle elected a Republican prosecutor (supported by most Democratic leaders). Uber-left Portland elected a prosecutor who was a Republican until recently. The Dallas mayor switched parties (from Democratic to Republican) out of frustration with progressive opposition to his (successful) efforts to cut crime by hiring and empowering more cops. New York elected a tough on crime (Democratic) former police captain to replace the prior progressive mayor. Even uber-progressives like Minnesota Governor and 2024 Democratic VP candidate Tim Walz did U-turns on issues such as whether police belong in schools, and what they can do while there.

Yet cops can do far more, and the Big Apple has shown the way. How that happened suggests that color matters, but the color is not Black so much as green.

New York City’s Turnaround: How a White Tourist’s Murder Made Black Lives Truly Matter

Sometimes history is shaped by unexpected (and undesirable) events that have positive impacts. A case in point is Brian Watkins, the 22-year-old White tourist from Provo, Utah, who was brutally murdered in front of his family on Labor Day Weekend in 1990 in NYC, while in town to watch the U.S. Open tennis tournament. His murder had historic impacts on New York, ultimately saving thousands of (mainly) Black lives, but it did not have the same impact nationally, a fact that says volumes about whose lives matter and why.

In 1990, New York City was among the most dangerous cities in the country. Today, as we show in our article “Which Police Departments Make Black Lives Matter?”22 despite high poverty, New York has the sixth lowest homicide rate among the 50 largest cities. That might not have happened without the brutal murder of Brian Watkins. As City Limits detailed in a 20-year retrospective23 on the Watkins killing, in 1990 New York City resembled the dystopian movie Escape from New York, with a record 2,245 homicides, including 75 murders of children under 16 and 35 killings of cab drivers, forced to risk their lives daily for their livelihoods. For their part, police, who found themselves outnumbered and sometimes outgunned, killed 41 civilians, around four times more than today.

The city that never sleeps was awash in blood, but NYC residents did not bleed equitably. Mainly, in what would turn out to be a common pattern, low-income minorities killed other low-income minorities in underpoliced neighborhoods. To use the first person for a bit, as I (Reilly) note in my 2020 book Taboo,24 and Rafael Mangual points out in his Criminal Injustice (2022),25 felony crime such as murder is remarkably concentrated by income and race. In my hometown of Chicago, the 10 relatively small community areas with the highest murder rates contain 53 percent of all recorded homicides in the city and have a total murder rate of 61.7/100,000, versus 18.2/100,000 for the rest of the city—with those districts included. In the even larger New York City, few wealthy businesspeople or tourists were affected by the most serious crime even during its horrendous peak.

Against that backdrop, after spending the day watching the U.S. Open, the Watkins family left their upscale hotel to enjoy Moroccan food in Greenwich Village. While waiting on a subway platform, they were assaulted by a “wolfpack” scouting for mugging victims so they could steal enough money to pay the $10-per-man cover charge at a nightclub.

In those bad old days, many young New Yorkers committed an occasional mugging to supplement their incomes, but this attack was unusually violent. In a matter of seconds, Brian Watkins’ brother and sister-in-law were roughed up while his father was knocked to the ground and slashed with a box-cutter, cutting his wallet out of his pocket. Brian’s mother was pulled down by her hair and kicked in the face and chest. While trying to protect her, Brian was fatally stabbed in the chest with a spring-handled butterfly knife. Not realizing the extent of his injury—a severed pulmonary artery—Brian chased the thieves until collapsing by a toll booth, dying shortly thereafter.

In 1990, New York City was among the most dangerous cities in the country. Today... despite high poverty, New York has the sixth lowest homicide rate among the 50 largest cities.

In Turnaround: How America’s Top Cop Reversed the Crime Epidemic,26 then-New York City Transit Police Chief and later NYPD Commissioner William Bratton recalled the Watkins killing as “among the worst nightmares” city leaders could imagine: “A tourist in the subway during a high-profile event with which the mayor is closely associated … gets stabbed and killed by a wolfpack. The murder made international headlines.”

Within hours a team of top cops apprehended the perpetrators, which just shows what police can do when a crime, such as the murder of a wealthy tourist, is made an actual priority. Twenty years later, rotting in a prison cell, Brian’s killer sadly recalled his decisions that night as the worst of his life. Had police been in control of the subways, the teen might have been deterred from making the decision that in essence ended two lives.

Unlike the great majority of the other 2,244 murder victims in 1990, the dead Brian mattered by name to Big Apple politicians. Bratton wrote that New York Governor Mario Cuomo “understood the impact this killing could have on New York tourism.” With hundreds of millions of dollars at stake, two days after the Watkins murder, Bratton got a call out of the blue from a top aid to the Governor asking whether transit police could make the subways safe if the state kicked in $40 million—big money in 1990. For Bratton, “this was the turnaround I needed.”

With the cash for more transit police, communications and data analytic tools to put cops where crimes occurred, and better police armaments, subway crime plummeted. Later, NYPD Commissioner Bratton drove homicide down by over a third in just two years with similar tactics, and by replacing hundreds of ineffective administrators with better leaders, as Patrick Wolf and one of us (Maranto) detail in “Cops, Teachers, and the Art of the Impossible: Explaining the Lack of Diffusion of Innovations That Make Impossible Jobs Possible.”27 In another article coauthored with Domonic Bearfield,28 we estimated that as of 2020, NYPD’s reforms saved over 20,000 lives, disproportionately of Black Americans.

NYPD leadership made ineffective leaders get better or get out. This is a tool almost never used by police reformers at the level of city governance.

So how did NYPD do it? New York got serious about both recruiting and training great, tough cops and about holding them accountable. In the 1990s, NYPD Commissioner William Bratton imposed CompStat, a statistical program reporting crimes by location in real time. In weekly meetings, NYPD leaders praised precinct commanders who cut crime and grilled others. They made ineffective managers get better or get out. Homicides fell by over a third in just two years, followed by steady declines since.

Let us repeat part of that for emphasis: NYPD leadership made ineffective leaders get better or get out. This is a tool almost never used by police reformers at the level of city governance, who don’t want to be hated by officers, and who are also hamstrung by civil service rules and union contracts that make it difficult to terminate bad police officers, and almost impossible to jettison bad managers. NYPD was the exception.

Because of obscure personnel reforms by Benjamin Ward, the first Black NYPD commissioner and someone who wanted to shake up NYPD’s Irish Mafia of officers, where promotion often depended on what some called “the friends and family plan,” NYPD commissioners have unusual power over personnel. The commissioner can bust precinct commanders and other key leaders back in rank almost to the street level. Since retirement is based on pay at an officer’s rank, this essentially forces managers into early retirement, with the commissioner getting to pick their replacements rather than having seniority or other civil service rules determine the outcomes.

Legendary police leader John Timoney, who was Bratton’s Chief of Department in NYPD before going on to successfully run departments in Philadelphia and Miami, told us that he had the ability to personally fire over 300 cops in NYPD compared to just two in Philadelphia—the two being himself and his driver. In the latter city, everyone else was covered by civil service tenure.29 Politicians such as Tim Walz were publicly emphasizing their focus on saving Black lives, but showed no enthusiasm for personnel reforms such as these, which could actually get the job done.

Of course, firing cops can’t work if you don’t know who to fire. Since the mid-1990s, NYPD strengthened its internal affairs unit to get off the streets unprofessional cops in the mold of Minneapolis’ Derek Chauvin, the officer who killed George Floyd and who had 18 prior citizen complaints, before rather than after a disaster. Longtime NYPD Internal Affairs leader Charles Campisi details this process well in Blue on Blue: An Insider’s Story of Good Cops Catching Bad Cops.30

Yet none of this might have happened without the brutal murder of Brian Watkins. In a real sense, the Watkins family suffered so thousands could live. They deserve a monument.

How to Make Black (and All) Lives Matter

Rather than supporting neo-Marxist activism portraying police as fascists enforcing “late-stage capitalist technocratic white supremacy,” or similarly impenetrable academic jargon that seeks to pit citizens against police and fails to solve problems, we see police departments as public organizations staffed by unionized employees, some of whom are public servants, some of whom mainly serve themselves, and most of whom are somewhere in between.31 Just like companies, some police departments are incredibly successful; some are so ineffective that it might make sense to defund them and start over … and some—most by far—are somewhere in between.

So the real question for those of us who want to make police better rather than run for office or get government grants, is how we can get low-performing police departments to learn from the best, and how we can get the mayors, city councils, governors, and state legislatures overseeing police to enact the sort of civil service reforms, like higher pay coupled with abolishing civil service tenure, that are likely to succeed in getting police to make all lives matter.

Black Lives Matter de-policing policies seem to have taken thousands of (mainly Black) lives. During the BLM era … the age-adjusted Black homicide rate has almost doubled, rising from 18.6 murders per 100,000 African-American citizens in 2011 to 32 murders per 100,000 in 2021.

For us, the key to get elected politicians to take police reform seriously is to make police reform a serious election issue, rather than how well one virtue signals for BLM. To do that, first and foremost, failed police departments and the mayors and city council members running them must be shamed into action. Businesses should be encouraged to relocate from dangerous cities to safe ones. That starts with data.

To make that happen, earlier this year, in a leading public administration journal, along with Patrick Wolf, we published “Which Police Departments Make Black Lives Matter?,” an article that anyone can download for free.32 Here, we ranked police in the 50 largest U.S. cities (using 2020 statistics, but the overall rankings were stable from 2015–2020) by their effectiveness in keeping homicides low and not taking civilian lives, while adjusting for poverty, which makes policing more difficult. Some departments excel. On our Police Professionalism Index, New York City easily takes first place, just as it did in 2015. The top 18 cities also include Boston, MA; Mesa, AZ; Raleigh, NC; Virginia Beach, VA; five California cities including San Diego and San Jose; and five Texas cities including El Paso and Austin.

In contrast, by a wide margin, Baltimore ranked dead last (as it did in 2015). Baltimore’s homicide rate (56.12 per 100,000 population) was roughly 15 times higher than New York’s, and Baltimore police kill roughly ten times as many civilians per capita as NYPD. Baltimoreans should be outraged, particularly since, as noted above, top-ranked NYPD used to be in Baltimore’s league. Fifty years ago, NYPD killed about 100 civilians annually, compared to 10 today. In 1990, New York City had 2,245 homicides, mostly people of color, compared to just 462 in 2020. And, as discussed earlier, reforming NYPD saved tens of thousands of lives, mainly Black lives, while at the same time reducing incarceration.

If democracy means anything, it means the ability to influence government, and the first duty of government is protecting life and property. For too long, this most basic of needs has been denied to people without means, who are disproportionately people of color. If we want to increase trust in government, we must start with the police. Doing that requires real data, not agitprop that paints cops as racist killers. To enable that, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) needs to rank large cities on their policing, in a manner we did, awarding those doing well and calling out those doing badly. The DOJ should also issue reports on which cities enable their police chiefs to terminate problematic officers.

This methodical approach would offend leftist cultural warriors and rightist police unions alike. On the local levels, to copy NYPD’s success, voters in Baltimore and other poorly policed cities such as Kansas City, Las Vegas, Albuquerque, and Miami, must ask pointed questions about their police, such as:

- Can police chiefs hire and retain the great officers they need? If not, why not?

- Can police chiefs fire subordinates who are not up to their tough jobs?

- Are there enough cops to do the job?

- Do police use CompStat to copy what works in fighting crime?

- Does the internal affairs unit hold brutal cops accountable?

Building a great police department takes time, but the NYPD has shown how it can be done. It is long past time to stop political virtue signaling and start reforming policing to save all lives.