From the Margins to the Mall: The Lifecycle of Subcultures

Founded in 1940, Pinnacle was a rural Jamaican commune providing its Black residents a “socialistic life” removed from the oppression of British colonialism. Its founder, Leonard Howell, preached an unorthodox mix of Christianity and Eastern spiritualism: Ethiopia’s Emperor Haile Selassie was considered divine, the Pope was the devil, and marijuana was a holy plant. Taking instructions from Leviticus 21:5, the men grew out their hair in a matted style that caused apprehension among outsiders, which was later called “dreadlocks.”

Jamaican authorities frowned upon the sect, frequently raiding Pinnacle and eventually locking up Howell in a psychiatric hospital. The crackdown drove Howell’s followers—who became known as Rastafarians—all throughout Jamaica, where they became regarded as folk devils. Parents told children that the Rastafarians lived in drainage ditches and carried around hacked-off human limbs. In 1960 the Jamaican prime minister warned the nation, “These people—and I am glad that it is only a small number of them—are the wicked enemies of our country.”

If Rastafarianism had disappeared at this particular juncture, we would remember it no more than other obscure modern spiritual sects, such as theosophy, the Church of Light, and Huna. But the tenets of Rastafarianism lived on, thanks to one extremely important believer: the Jamaican musician Bob Marley. He first absorbed the group’s teachings from the session players and marijuana dealers in his orbit. But when his wife, Rita, saw Emperor Haile Selassie in the flesh—and a stigmata-like “nail-print” on his hand—she became a true believer. Marley eventually took up its credo, and as his music spread around the world in the 1970s, so did the conventions of Rastafarianism—from dreadlocks, now known as “locs,” as a fashionable hairstyle to calling marijuana “ganja.”

Individuals joined subcultures and countercultures to reject mainstream society and its values. They constructed identities through an open disregard for social norms.

Using pop music as a vehicle, the tenets of a belittled religious subculture on a small island in the Caribbean became a part of Western commercial culture, manifesting in thousands of famed musicians taking up reggae influences, suburban kids wearing knitted “rastacaps” at music festivals, and countless red, yellow, and green posters of marijuana leaves plastering the walls of Amsterdam coffeehouses and American dorm rooms. Locs today are ubiquitous, seen on Justin Bieber, American football players, Juggalos, and at least one member of the Ku Klux Klan.

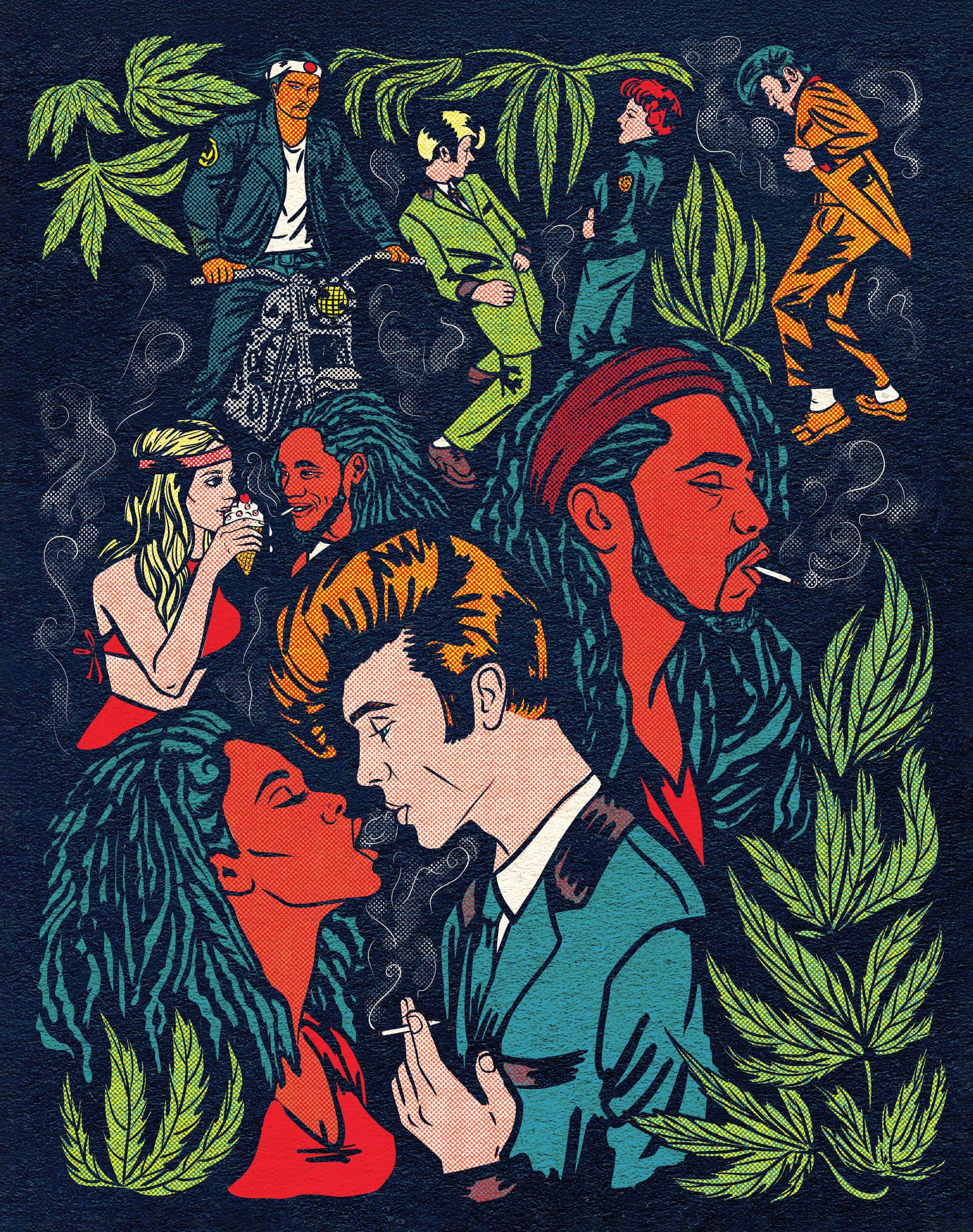

Rastafarianism is not an exception: The radical conventions of teddy boys, mods, rude boys, hippies, punks, bikers, and surfers have all been woven into the mainstream. That was certainly not the groups’ intention. Individuals joined subcultures and countercultures to reject mainstream society and its values. They constructed identities through an open disregard for social norms. Yet in rejecting basic conventions, these iconoclasts became legendary as distinct, original, and authentic. Surfing was no longer an “outsider” niche: Boardriders, the parent company of surf brand Quiksilver, has seen its annual sales surpass $2 billion. Country Life English Butter hired punk legend John Lydon to appear in television commercials. One of America’s most beloved ice cream flavors is Cherry Garcia, named after the bearded leader of a psychedelic rock band who long epitomized the “turn on, tune in, drop out” spirit of 1960s countercultural rebellion. As the subcultural scholars Stuart Hall and Tony Jefferson note, oppositional youth cultures became a “pure, simple, raging, commercial success.” So why, exactly, does straight society come to champion extreme negations of its own conventions?

Subcultures and countercultures manage to achieve a level of influence that belies their raw numbers. Most teens of the 1950s and 1960s never joined a subculture. There were never more than an estimated thirty thousand British teddy boys in a country of fifty million people. However alienated teens felt, most didn’t want to risk their normal status by engaging in strange dress and delinquent behaviors. Because alternative status groups can never actually replace the masses, they can achieve influence only through being imitated. But how do their radical inventions take on cachet? There are two key pathways: the creative class and the youth consumer market.

In the basic logic of signaling, subcultural conventions offer little status value, as they are associated with disadvantaged communities. The major social change of the twentieth century, however, was the integration of minority and working-class conventions into mainstream social norms. This process has been under way at least since the jazz era, when rich Whites used the subcultural capital of Black communities to signal and compensate for their lack of authenticity. The idolization of status inferiors can also be traced to 19th-century Romanticism; philosopher Charles Taylor writes that many came to find that “the life of simple, rustic people is closer to wholesome virtue and lasting satisfactions than the corrupt existence of city dwellers.” By the late 1960s, New York high society threw upscale cocktail parties for Marxist radicals like the Black Panthers—a predilection Tom Wolfe mocked as “radical chic.”

For most cases in the twentieth century, however, the creative class became the primary means by which conventions from alternative status groups nestled into the mainstream. This was a natural process, since many creatives were members of countercultures, or at least were sympathetic to their ideals. In The Conquest of Cool, historian Thomas Frank notes that psychedelic art appeared in commercial imagery not as a means of pandering to hippie youth but rather as the work of proto-hippie creative directors who foisted their lysergic aesthetics on the public. Hippie ads thus preceded—and arguably created—hippie youth.

Because alternative status groups can never actually replace the masses, they can achieve influence only through being imitated.

This creative-class counterculture link, however, doesn’t explain the spread of subcultural conventions from working-class communities like the mods or Rastafarians. Few from working-class subcultures go into publishing and advertising. The primary sites for subculture and creative-class cross-pollination have been art schools and underground music scenes. The punk community, in particular, arose as an alliance between the British working class and students in art and fashion schools. Once this network was formed, punk’s embrace of reggae elevated Jamaican music into the British mainstream as well. Similarly, New York’s downtown art scene supported Bronx hip-hop before many African American radio stations took rap seriously.

Subcultural style often fits well within the creative-class sensibility. With a premium placed on authenticity, creative class taste celebrates defiant groups like hipsters, surfers, bikers, and punks as sincere rejections of the straight society’s “plastic fantastic” kitsch. The working classes have a “natural” essence untarnished by the demands of bourgeois society. “What makes Hip a special language,” writes Norman Mailer, “is that it cannot really be taught.” This perspective can be patronizing, but to many middle-class youth, subcultural style is a powerful expression of earnest antagonism against common enemies. Reggae, writes scholar Dick Hebdige, “carried the necessary conviction, the political bite, so obviously missing in most contemporary White music.”

From the jazz era onward, knowledge of underground culture served as an important criterion for upper-middle-class status—a pressure to be hip, to be in the know about subcultural activity. Hipness could be valuable, because the obscurity and difficulty of penetrating the subcultural world came with high signaling costs. Once subcultural capital became standard in creative-class signaling, minority and working-class slang, music, dances, and styles functioned as valuable signals—with or without their underlying beliefs. Art school students could listen to reggae without believing in the divinity of Haile Selassie. For many burgeoning creative-class members, subcultures and countercultures offered vehicles for daydreaming about an exciting life far from conformist boredom. Art critic Dan Fox, who grew up in the London suburbs, explains, “[Music-related tribe] identities gave shelter, a sense of belonging; being someone else was a way to fantasize your exit from small-town small-mindedness.”

Middle-class radical chic, however, tends to denature the most prickly styles. This makes “radical” new ideas less socially disruptive, which opens a second route of subcultural influence: the youth consumer market. The culture industry—fashion brands, record companies, film producers—is highly attuned to the tastes of the creative class, and once the creative class blesses a subculture or counterculture, companies manufacture and sell wares to tap into this new source of cachet. At first mods tailored their suits, but the group’s growing stature encouraged ready-to-wear brands to manufacture off-the-rack mod garments for mass consumption. As the punk trend flared in England, the staid record label EMI signed the Sex Pistols (and then promptly dropped them). With so many cultural trends starting among the creative classes and ethnic subcultures, companies may not understand these innovations but gamble that they will be profitable in their appeal to middle-class youth.

Before radical styles can diffuse as products, they are defused—i.e., the most transgressive qualities are surgically removed. Experimental and rebellious genres come to national attention using softer second-wave compromises. In the early 1990s, hip-hop finally reached the top of the charts with the “pop rap” of MC Hammer and Vanilla Ice. Defusing not only dilutes the impact of the original inventions but also freezes farout ideas into set conventions. The vague “oppositional attitude” of a subculture becomes petrified in a strictly defined set of goods. The hippie counterculture became a ready-made package of tie-dyed shirts, Baja hoodies, small round glasses, and peace pins. Mass media, in needing to explain subcultures to readers, defines the undefined—and exaggerates where necessary. Velvet cuffs became a hallmark of teddy boy style, despite being a late-stage development dating from a single 1957 photo in Teen Life magazine.

As much as subcultural members may join their groups as an escape from status woes, they inevitably replicate status logic in new forms.

This simplification inherent in the marketing process lowers fences and signaling costs, allowing anyone to be a punk or hip-hopper through a few commercial transactions. John Waters took interest in beatniks not for any “deep social conviction” but “in homage” to his favorite TV character, Maynard G. Krebs, on The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis. And as more members rush into these groups, further simplification occurs. Younger members have less money to invest in clothing, vehicles, and conspicuous hedonism. The second generation of teds maintained surly attitudes and duck’s-ass quiffs, but replaced the Edwardian suits with jeans. Creative classes may embrace subcultures and countercultures on pseudo-spiritual grounds, but many youth simply deploy rebellious styles as a blunt invective against adults. N.W.A’s song “Fuck tha Police” gave voice to Black resentment against Los Angeles law enforcement; White suburban teens blasted it from home cassette decks to anger their parents.

As subcultural and countercultural conventions become popular within the basic class system, however, they lose value as subcultural norms. Most alternative status groups can’t survive the parasitism of the consumer market; some fight back before it’s too late. In October 1967, a group of longtime countercultural figures held a “Death of the Hippie” mock funeral on the streets of San Francisco to persuade the media to stop covering their movement. Looking back at the sixties, journalist Nik Cohn noted that these groups’ rise and fall always followed a similar pattern:

One by one, they would form underground and lay down their basic premises, to be followed with near millennial fervor by a very small number; then they would emerge into daylight and begin to spread from district to district; then they would catch fire suddenly and produce a national explosion; then they would attract regiments of hangers-on and they would be milked by industry and paraded endlessly by media; and then, robbed of all novelty and impact, they would die.

By the late 1960s the mods’ favorite hangout, Carnaby Street, had become “a tourist trap, a joke in bad taste” for “middle-aged tourists from Kansas and Wisconsin.” Japanese biker gangs in the early 1970s dressed in 1950s Americana—Hawaiian shirts, leather jackets, jeans, pompadours—but once the mainstream Japanese fashion scene began to play with a similar fifties retro, the bikers switched to right-wing paramilitary uniforms festooned with imperialist slogans.

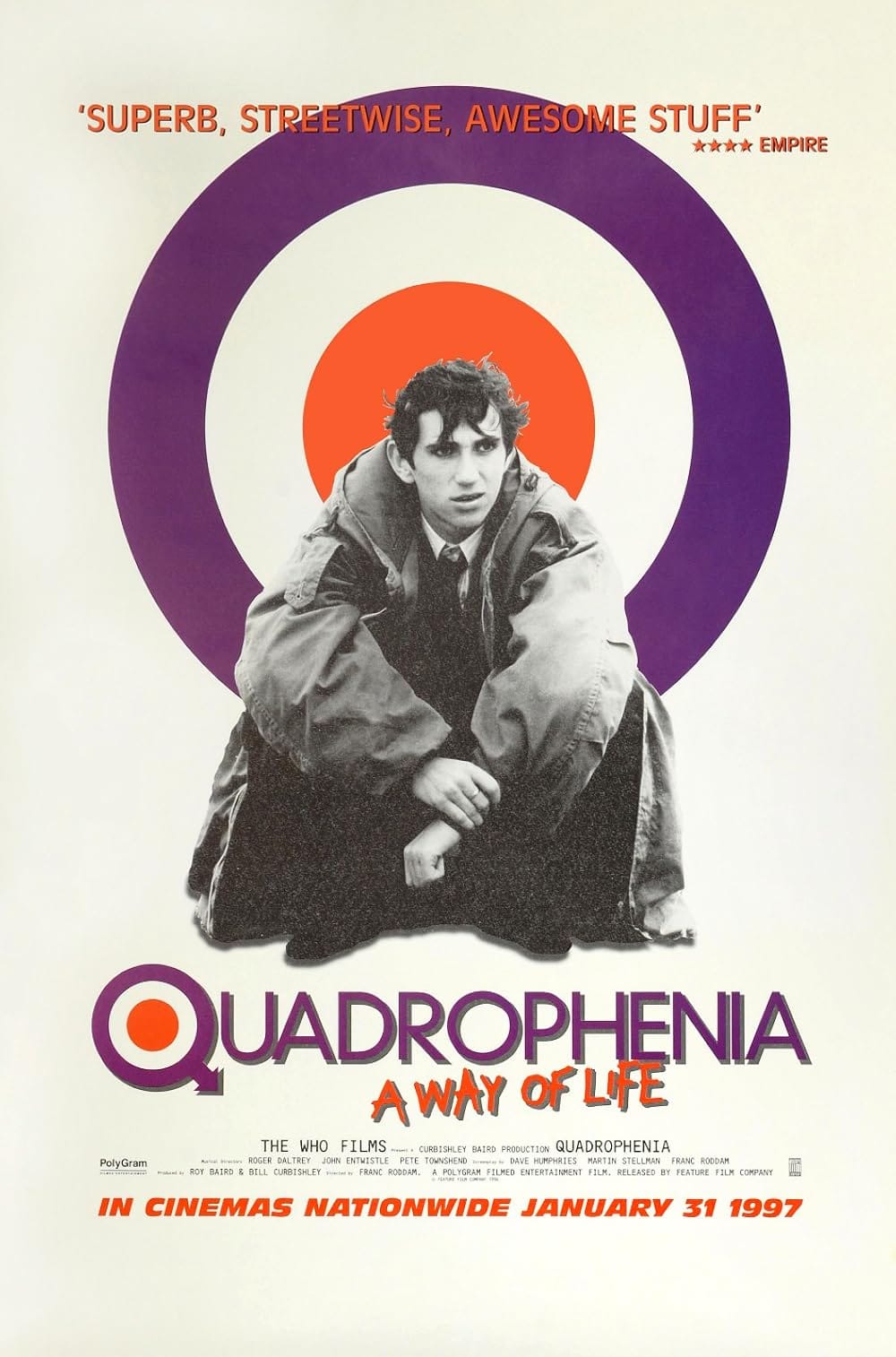

However, what complicates any analysis of subcultural influence on mainstream style is that the most famous 1960s groups often reappear as revival movements. Every year a new crop of idealistic young mods watches the 1979 film Quadrophenia and rushes out to order their first tailored mohair suit. We shouldn’t confuse these later adherents, however, as an organic extension of the original configuration. New mods are seeking comfort in a presanctioned rebellion, rather than spearheading new shocking styles at the risk of social disapproval. The neoteddy boys of the 1970s adopted the old styles as a matter of pure taste: namely, a combination of fifties rock nostalgia and hippie backlash. Many didn’t even know where the term “Edwardian” originated.

Were the original groups truly “subcultural” if they could be so seamlessly absorbed into the commercial marketplace? In the language of contemporary marketing, “subculture” has come to mean little more than “niche consumer segment.” A large portion of contemporary consumerism is built on countercultural and subcultural aesthetics. Formerly antisocial looks like punk, hippie, surfer, and biker are now sold as mainstream styles in every American shopping mall. Corporate executives brag about surfing on custom longboards, road tripping on Harley-Davidsons, and logging off for weeks while on silent meditation retreats. The high-end fashion label Saint Laurent did a teddy-boy-themed collection in 2014, and Dior took inspiration from teddy girls for the autumn of 2019. There would be no Bobo yuppies in Silicon Valley without bohemianism, nor would the Police’s “Roxanne” play as dental-clinic Muzak without Jamaican reggae.

Alternative status groups in the twentieth century did, however, succeed in changing the direction of cultural flows.

But not all subcultures and countercultures have ended up as part of the public marketplace. Most subcultures remain marginalized: e.g., survivalists, furries, UFO abductees, and pickup artists. Just like teddy boys, the Juggalos pose as outlaws with their own shocking music, styles, and dubious behaviors—and yet the music magazine Blender named the foundational Juggalo musical act Insane Clown Posse as the worst artist in music history. The movement around Christian rock has suffered a similar fate; despite staggering popularity, the fashion brand Extreme Christian Clothes has never made it into the pages of GQ. Since these particular groups are formed from elements of the (White) majority culture—rather than formed in opposition to it—they offer left-leaning creatives no inspiration. Lower-middle-class White subcultures can also epitomize the depths of conservative sentiment rather than suggest a means of escape. Early skinhead culture influenced high fashion, but the Nazi-affiliated epigones didn’t. Without the blessing of the creative class, major manufacturers won’t make new goods based on such subcultures’ conventions, preventing their spread to wider audiences. Subcultural transgressions, then, best find influence when they become signals within the primary status structure of society.

The renowned scholarship on subcultures produced at Birmingham’s Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies casts youth groups as forces of “resistance,” trying to navigate the “contradictions” of class society. Looking back, few teds or mods saw their actions in such openly political terms. “Studies carried out in Britain, America, Canada, and Australia,” writes sociologist David Muggleton, “have, in fact, found subcultural belief systems to be complex and uneven.” While we may take inspiration from the groups’ sense of “vague opposition,” we’re much more enchanted by their specific garments, albums, dances, behaviors, slang, and drugs. In other words, each subculture and counterculture tends to be reduced to a set of cultural artifacts, all of which are added to the pile of contemporary culture.

The most important contribution of subcultures, however, has been giving birth to new sensibilities— additional perceptual frames for us to revalue existing goods and behaviors. From the nineteenth century onward, gay subcultures have spearheaded the camp sensibility—described by Susan Sontag as a “love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration,” including great sympathy for the “old-fashioned, out-of-date, démodé.” This “supplementary” set of standards expanded cultural capital beyond high culture and into an ironic appreciation of low culture. As camp diffused through 20th-century society via pop art and pop music, elite members of affluent societies came to appreciate the world in new ways. Without the proliferation of camp, John Waters would not grace the cover of Town & Country.

The fact that subcultural rebellion manifests as a simple distinction in taste is why the cultural industry can so easily co-opt its style.

As much as subcultural members may join their groups as an escape from status woes, they inevitably replicate status logic in new forms—different status criteria, different hierarchies, different conventions, and different tastes. Members adopt their own arbitrary negations of arbitrary mainstream conventions, but believe in them as authentic emotions. If punk were truly a genuine expression of individuality, as John Lydon claims it should be, there could never have been a punk “uniform.”

The fact that subcultural rebellion manifests as a simple distinction in taste is why the cultural industry can so easily co-opt its style. If consumers are always on the prowl for more sensational and more shocking new products, record companies and clothing labels can use alternative status groups as R&D labs for the wildest new ideas.

Alternative status groups in the twentieth century did, however, succeed in changing the direction of cultural flows. In strict class-based societies of the past, economic capital and power set rigid status hierarchies; conventions trickled down from the rich to the middle classes to the poor. In a world where subcultural capital takes on cachet, the rich consciously borrow ideas from poorer groups. Furthermore, bricolage is no longer a junkyard approach to personal style—everyone now mixes and matches. In the end, subcultural groups were perhaps an avant-garde of persona crafting, the earliest adopters of the now common practice of inventing and performing strange characters as an effective means of status distinction.

For both classes and alternative status groups, individuals pursuing status end up forming new conventions without setting out to do so. Innovation, in these cases, is often a byproduct of status struggle. But individuals also intentionally attempt to propose alternatives to established conventions. Artists are the most well-known example of this more calculated creativity—and they, too, are motivated by status.

Subcultures and countercultures are often cast as modern folk devils. The media spins lurid yarns of criminal destruction, drug abuse, and sexual immorality.

Not surprisingly, mainstream society reacts with outrage upon the appearance of alternative status groups, as these groups’ very existence is an affront to the dominant status beliefs. Blessing or even tolerating subcultural transgressions is a dangerous acknowledgment of the arbitrariness of mainstream norms. Thus, subcultures and countercultures are often cast as modern folk devils. The media spins lurid yarns of criminal destruction, drug abuse, and sexual immorality—frequently embellishing with sensational half-truths. To discourage drug use in the 1970s, educators and publishers relied on a fictional diary called Go Ask Alice, in which a girl takes an accidental dose of LSD and falls into a tragic life of addiction, sex work, and homelessness. The truth of subcultural life is often more pedestrian. As an early teddy boy explained in hindsight, “We called ourselves Teddy Boys and we wanted to be as smart as possible. We lived for a good time, and all the rest was propaganda.”

Excerpted and adapted by the author from Status and Culture by W. David Marx, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. © 2022 by W. David Marx.