Throughout the early modern period—from the rise of the nation state through the nineteenth century—the predominant economic ideology of the Western world was mercantilism, or the belief that nations compete for a fixed amount of wealth in a zero-sum game: the +X gain of one nation means the –X loss of another nation, with the +X and –X summing to zero. The belief at the time was that in order for a nation to become wealthy, its government must run the economy from the top down through strict regulation of foreign and domestic trade, enforced monopolies, regulated trade guilds, subsidized colonies, accumulation of bullion and other precious metals, and countless other forms of economic intervention, all to the end of producing a “favorable balance of trade.” Favorable, that is, for one nation over another nation. As President Donald Trump often repeats, “they’re ripping us off!” That is classic mercantilism and economic nationalism speaking.

Adam Smith famously debunked mercantilism in his 1776 treatise An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Smith’s case against mercantilism is both moral and practical. It is moral, he argued, because: “To prohibit a great people…from making all that they can of every part of their own produce, or from employing their stock and industry in the way that they judge most advantageous to themselves, is a manifest violation of the most sacred rights of mankind.”1 It is practical, he showed, because: “Whenever the law has attempted to regulate the wages of workmen, it has always been rather to lower them than to raise them.”2

Producers and Consumers

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations was one long argument against the mercantilist system of protectionism and special privilege that in the short run may benefit producers but which in the long run harms consumers and thereby decreases the wealth of a nation. All such mercantilist practices benefit the producers, monopolists, and their government agents, while the people of the nation—the true source of a nation’s wealth—remain impoverished: “The wealth of a country consists, not of its gold and silver only, but in its lands, houses, and consumable goods of all different kinds.” Yet, “in the mercantile system, the interest of the consumer is almost always constantly sacrificed to that of the producer.”3

The solution? Hands off. Laissez Faire. Lift trade barriers and other restrictions on people’s economic freedoms and allow them to exchange as they see fit for themselves, both morally and practically. In other words, an economy should be consumer driven, not producer driven. For example, under the mercantilist zero-sum philosophy, cheaper foreign goods benefit consumers but they hurt domestic producers, so the government should impose protective trade tariffs to maintain the favorable balance of trade.

But who is being protected by a protective tariff? Smith showed that, in principle, the mercantilist system only benefits a handful of producers while the great majority of consumers are further impoverished because they have to pay a higher price for foreign goods. The growing of grapes in France, Smith noted, is much cheaper and more efficient than in the colder climes of his homeland, for example, where “by means of glasses, hotbeds, and hotwalls, very good grapes can be raised in Scotland” but at a price thirty times greater than in France. “Would it be a reasonable law to prohibit the importation of all foreign wines, merely to encourage the making of claret and burgundy in Scotland?” Smith answered the question by invoking a deeper principle:

What is prudence in the conduct of every private family, can scarce be folly in that of a great kingdom. If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them.4

This is the central core of Smith’s economic theory: “Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production; and the interest of the producer ought to be attended to, only so far as it may be necessary for promoting that of the consumer.” The problem is that the system of mercantilism “seems to consider production, and not consumption, as the ultimate end and object of all industry and commerce.”5 So what?

When production is the object, and not consumption, producers will appeal to top-down regulators instead of bottom-up consumers. Instead of consumers telling producers what they want to consume, government agents and politicians tell consumers what, how much, and at what price the products and services will be that they consume. This is done through a number of different forms of interventions into the marketplace. Domestically, we find examples in tax favors for businesses, tax subsidies for corporations, regulations (to control prices, imports, exports, production, distribution, and sales), and licensing (to control wages, protect jobs).6 Internationally, the interventions come primarily through taxes under varying names, including “duties,” “imposts,” “excises,” “tariffs,” “protective tariffs,” “import quotas,” “export quotas,” “most-favored nation agreements,” “bilateral agreements,” “multilateral agreements,” and the like.

Such agreements are never between the consumers of two nations; they are between the politicians and the producers of the nations. Consumers have no say in the matter, with the exception of indirectly voting for the politicians who vote for or against such taxes and tariffs. And they all sum to the same effect: the replacement of free trade with “fair trade” (fair for producers, not consumers), which is another version of the mercantilist “favorable balance of trade” (favorable for producers, not consumers). Mercantilism is a zero-sum game in which producers win by the reduction or elimination of competition from foreign producers, while consumers lose by having fewer products from which to choose, along with higher prices and often lower quality products. The net result is a decrease in the wealth of a nation.

The principle is as true today as it was in Smith’s time, and we still hear the same objections Smith did: “Shouldn’t we protect our domestic producers from foreign competition?” And the answer is the same today as it was two centuries ago: no, because “consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production.”

Nonzero Economics

The founders of the United States and the framers of the Constitution were heavily influenced by the Enlightenment thinkers of England and the continent, including and especially Adam Smith. Nevertheless, it was not long after the founding of the country before our politicians began to shift the focus of the economy from consumption to production. In 1787, the United States Constitution was ratified, which included Article 1, Section 8: “The Congress shall have the power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises to cover the debts of the United States.” As an amusing exercise in bureaucratic wordplay, consider the common usages of these terms in the Oxford English Dictionary.

Tax: “a compulsory contribution to the support of government”

Duty: “a payment to the public revenue levied upon the import, export, manufacture, or sale of certain commodities”

Impost: “a tax, duty, imposition levied on merchandise”

Excise: “any toll or tax.”

(Note the oxymoronic phrase “compulsory contribution” in the first definition.)

A revised Article 1, Section 8 reads: “The Congress shall have the power to lay and collect taxes, taxes, taxes, and taxes to cover the debts of the United States.”

In the U.K. and on the continent, mercantilists dug in while political economists, armed with the intellectual weapons provided by Adam Smith, fought back, wielding the pen instead of the sword. The nineteenth-century French economist Frédéric Bastiat, for example, was one of the first political economists after Smith to show what happens when the market depends too heavily on top-down tinkering from the government. In his wickedly raffish The Petition of the Candlemakers, Bastiat satirizes special interest groups—in this case candlemakers—who petition the government for special favors:

We are suffering from the ruinous competition of a foreign rival who apparently works under conditions so far superior to our own for the production of light, that he is flooding the domestic market with it at an incredibly low price.... This rival... is none other than the sun.... We ask you to be so good as to pass a law requiring the closing of all windows, dormers, skylights, inside and outside shutters, curtains, casements, bull’s-eyes, deadlights and blinds; in short, all openings, holes, chinks, and fissures.7

Zero-sum mercantilist models hung on through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, even in America. Since the income tax was not passed until 1913 through the Sixteenth Amendment, for most of the country’s first century the practitioners of trade and commerce were compelled to contribute to the government through various other taxes. Since foreign trade was not able to meet the growing debts of the United States, and in response to the growing size and power of the railroads and political pressure from farmers who felt powerless against them, in 1887 the government introduced the Interstate Commerce Commission. The ICC was charged with regulating the services of specified carriers engaged in transportation between states, beginning with railroads, but then expanded the category to include trucking companies, bus lines, freight carriers, water carriers, oil pipelines, transportation brokers, and other carriers of commerce.8 Regardless of its intentions, the ICC’s primary effect was interference with the freedom of people to buy and sell between the states of America.

The ICC was followed in 1890 with the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, which declared: “Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal. Every person who shall make any contract or engage in any combination or conspiracy hereby declared to be illegal shall be deemed guilty of a felony,” resulting in a massive fine, jail, or both.

When stripped of its obfuscatory language, the Sherman Anti-Trust Act and the precedent-setting cases that have been decided in the courts in the century since it was passed, allows the government to indict an individual or a company on one or more of four crimes:

- Price gouging (charging more than the competition)

- Cutthroat competition (charging less than the competition)

- Price collusion (charging the same as the competition), and

- Monopoly (having no competition).9, 10

This was Katy-bar-the-door for anti-business legislators and their zero-sum mercantilist bureaucrats to restrict the freedom of consumers and producers to buy and sell, and they did with reckless abandon.

Completing Smith’s Revolution

Tariffs are premised on a win-lose, zero-sum, producer-driven economy, which ineluctably leads to consumer loss. By contrast, a win-win, nonzero, consumer-driven economy leads to consumer gain. Ultimately, Smith held, a consumer-driven economy will produce greater overall wealth in a nation than will a producer-driven economy. Smith’s theory was revolutionary because it is counterintuitive. Our folk economic intuitions tell us that a complex system like an economy must have been designed from the top down, and thus it can only succeed with continual tinkering and control from the top. Smith amassed copious evidence to counter this myth—evidence that continues to accumulate two and a half centuries later—to show that, in the modern language of complexity theory, the economy is a bottom-up self-organized emergent property of complex adaptive systems.

Adam Smith launched a revolution that has yet to be fully realized. A week does not go by without a politician, economist, or social commentator bemoaning the loss of American jobs, American manufacturing, and American products to foreign jobs, foreign manufacturing, and foreign products. Even conservatives—purportedly in favor of free markets, open competition, and less government intervention in the economy—have few qualms about employing protectionism when it comes to domestic producers, even at the cost of harming domestic consumers.

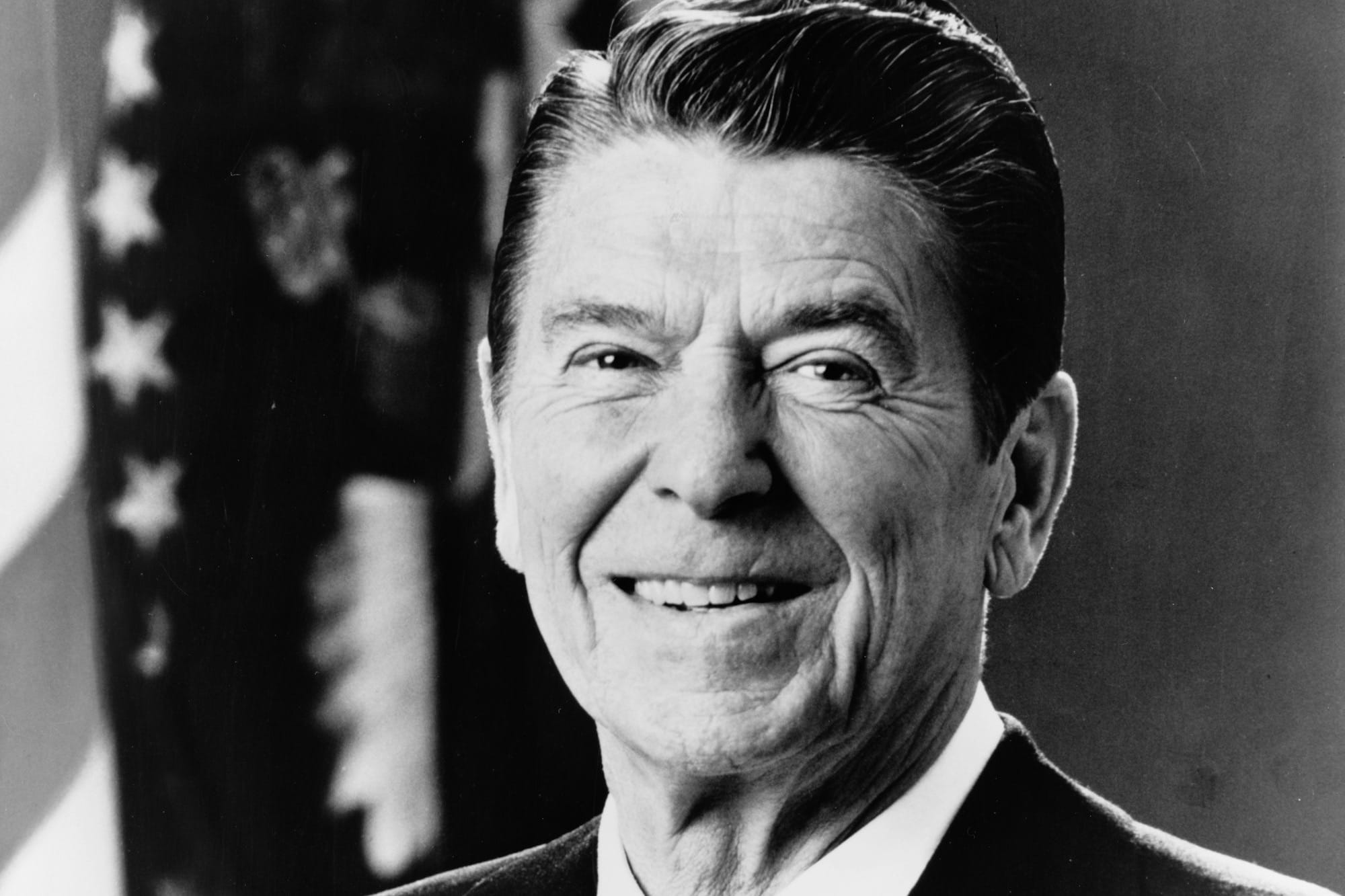

Even the icon of free market capitalism, President Ronald Reagan, compromised his principles in 1982 to protect the Harley-Davidson Motor Company when it was struggling to compete against Japanese motorcycle manufactures that were producing higher quality bikes at lower prices. Honda, Kawasaki, Yamaha, and Suzuki were routinely undercutting Harley-Davidson by $1500 to $2000 a bike in comparable models.

On January 19, 1983, the International Trade Commission ruled that foreign motorcycle imports were a threat to domestic motorcycle manufacturers, and a 2-to-1 finding of injury was ruled on petition by Harley-Davidson, which complained that it could not compete with foreign motorcycle producers.10 On April 1, Reagan approved the ITC recommendation, explaining to Congress, “I have determined that import relief in this case is consistent with our national economic interest,” thereby raising the tariff from 4.4 percent to 49.4 percent for a year, a ten-fold tax increase on foreign motorcycles that was absorbed by American consumers. The protective tariff worked to help Harley-Davidson recover financially, but it was American motorcycle consumers who paid the price, not Japanese producers. As the ITC Chairman Alfred E. Eckes explained about his decision: “In the short run, price increases may have some adverse impact on consumers, but the domestic industry’s adjustment will have a positive long-term effect. The proposed relief will save domestic jobs and lead to increased domestic production of competitive motorcycles.”11

Whenever free trade agreements are proposed that would allow domestic manufacturers to produce their goods cheaper overseas and thereby sell them domestically at a much lower price than they could have with domestic labor, politicians and economists, often under pressure from trade unions and political constituents, routinely respond disapprovingly, arguing that we must protect our domestic workers. Recall Presidential candidate Ross Perot’s oft-quoted 1992 comment in response to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) about the “giant sucking sound” of jobs being sent to Mexico from the United States.

In early 2007, the Nobel laureate economist Edward C. Prescott lamented that economists invest copious time and resources countering the myth that it is “the government’s economic responsibility to protect U.S. industry, employment and wealth against the forces of foreign competition.” That is not the government’s responsibility, says Prescott, echoing Smith, which is simply “to provide the opportunity for people to seek their livelihood on their own terms, in open international markets, with as little interference from government as possible.” Prescott shows that “those countries that open their borders to international competition are those countries with the highest per capita income” and that open economic borders “is the key to bringing developing nations up to the standard of living enjoyed by citizens of wealthier countries.”12

“Protectionism is seductive,” Prescott admits, “but countries that succumb to its allure will soon have their economic hearts broken. Conversely, countries that commit to competitive borders will ensure a brighter economic future for their citizens.” But why exactly do open economic borders, free trade, and international competition lead to greater wealth for a nation? Writing over two centuries after Adam Smith, Prescott reverberates the moral philosopher’s original insight:

It is openness that gives people the opportunity to use their entrepreneurial talents to create social surplus, rather than using those talents to protect what they already have. Social surplus begets growth, which begets social surplus, and so on. People in all countries are motivated to improve their condition, and all countries have their share of talented risk-takers, but without the promise that a competitive system brings, that motivation and those talents will only lie dormant.13

The Evolutionary Origins of Tariffs and Zero-Sum Economics

Why is mercantilist zero-sum protectionism so pervasive and persistent? Bottom-up invisible hand explanations for complex systems are counterintuitive because of our folk economic propensity to perceive designed systems to be the product of a top-down designer. But there is a deeper reason grounded in our evolved social psychology of group loyalty. The ultimate reason that Smith’s revolution has not been fulfilled is that we evolved a propensity for in-group amity and between-group enmity, and thus it is perfectly natural to circle the wagons and protect one’s own, whoever or whatever may be the proxy for that group. Make America Great Again!

For the first 90,000 years of our existence as a species we lived in small bands of tens to hundreds of people. In the last 10,000 years some bands evolved into tribes of thousands, some tribes developed into chiefdoms of tens of thousands, some chiefdoms coalesced into states of hundreds of thousands, and a handful of states conjoined together into empires of millions. The attendant leap in food-production and population that accompanied the shift to chiefdoms and states allowed for a division of labor to develop in both economic and social spheres. Full-time artisans, craftsmen, and scribes worked within a social structure organized and run by full-time politicians, bureaucrats, and, to pay for it all, tax collectors. The modern state economy was born.

In this historical trajectory our group psychology evolved and along with it a propensity for xenophobia—in-group good, out-group bad. In the Paleolithic social environment in which our moral commitments evolved, one’s fellow in-group members consisted of family, extended family, friends, and community members who were well known to each other. To help others was to help oneself. Those groups who practiced in-group harmony and between-group antagonism would have had a survival advantage over those groups who experienced within-group social divide and decoherence, or haphazardly embraced strangers from other groups without first establishing trust. Because our deep social commitments evolved as part of our behavioral repertoire of responses for survival in a complex social environment, we carry the seeds of such in-group inclusiveness today. The resulting within-group cohesiveness and harmony carries with it a concomitant tendency for between-group xenophobia and tribalism that, in the context of a modern economic system, leads to protectionism and mercantilism.

And tariffs. We must resist the tribal temptation.